Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown, Playhouse Theatre, review: Tamsin Greig is tremendous

There's a dream-like fluidity to the craziness here which is played out on a white, split-level apartment set

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference."The most expensive out-of-town try-out in theatre history," is director Bartlett Sher's joky description of the brief New York run in 2010 of this musical comedy adaptation of Pedro Almodovar's celebrated 1988 movie.

He's earned the right to that rueful quip because, for this London premiere, its creators have reworked the show, which has a score by David Yazbeck and book by Jeffrey Lane, so that it boasts a focus and intimacy felt to be sorely lacking in the over-produced original incarnation.

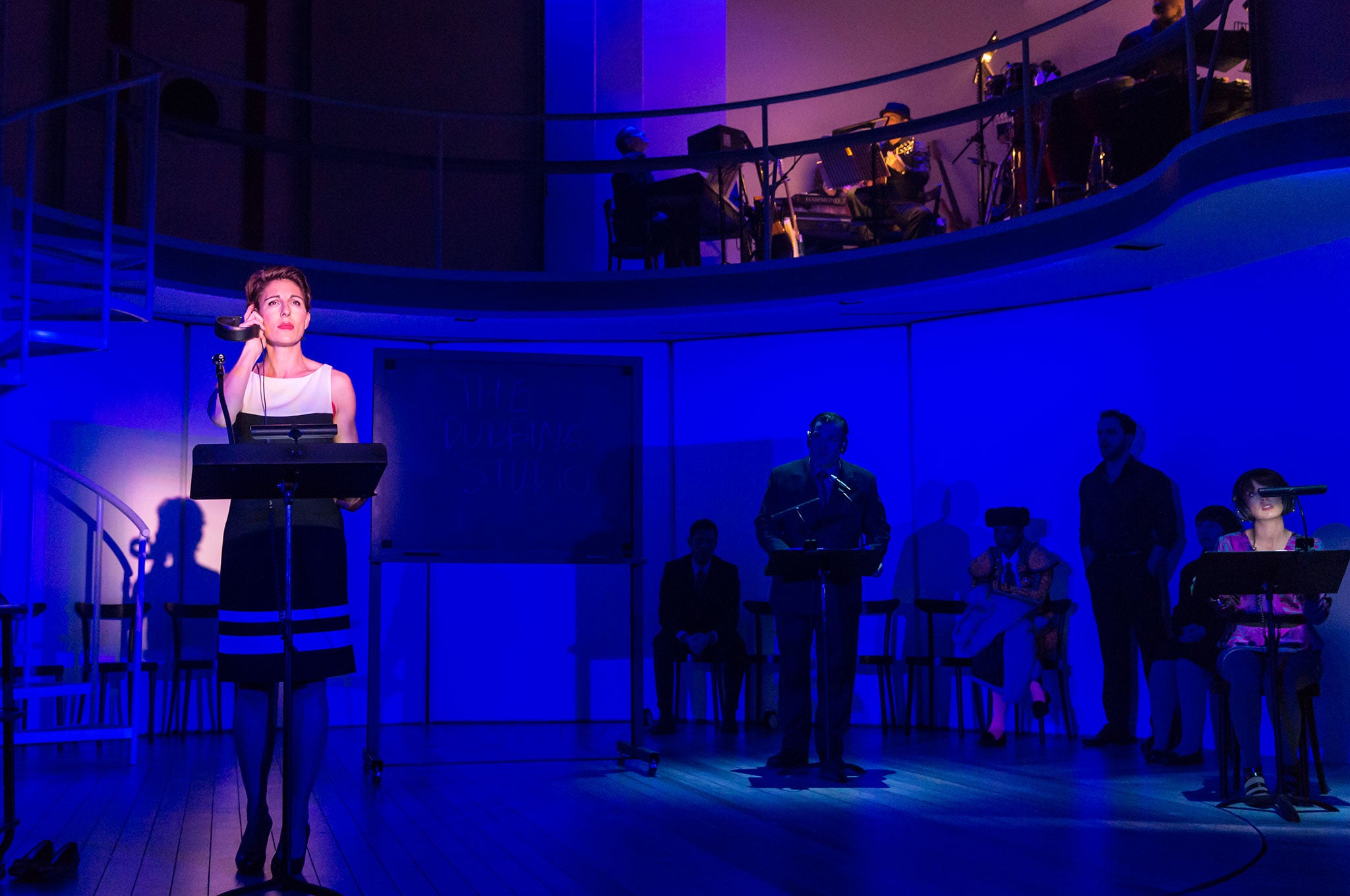

There's a dream-like fluidity to the craziness here which is played out on a white, split-level apartment set, suffused with the shifting lilacs, peaches and limes of Peter Mumford's lovely lighting design that acts as the equivalent of the stylised, candy-coloured gaudiness of the look given to liberated, late 1980s Madrid in the movie.

There are mercifully no funny-foreigner accents. But the music, performed by a visible six-strong band, has a distinctly Spanish flavour with its mambo rhythms and a stabbing energy that powerfully projects the emotional agitation of the characters.

An intermittent figure in the film, the taxi-driver (charmingly portrayed and resonantly sung here by Ricardo Afonso) now becomes the action's impish, guitar strumming chorus, self-professedly addicted to the nipple of "mama Madrid".

The production's masterstroke is the casting of Tamsin Greig in the central role of Pepa, the actress and voice-over artist who is dumped by her lover and finds herself embroiled in a barkingly tangled plot involving his mad, vengeful wife, who has just released from the asylum after twenty years, his son and the son's fiancee, and a fashion model friend demented to discover she's been dating a Shi-ite terrorist.

Greig's superb timing and her matchless ability to flicker between comic absurdity and desolate melancholy and to show the perilous closeness of shaking with laughter and shivering with tears are tremendous assets for a piece that proves there's no incongruity between frenetic farce and the expression through song of the fraught emotions that fuel it.

All the women in this gloriously camp yet seriously heartfelt celebration of female powers of survival and self-emancipation have been abandoned by men.

There's a wonderfully jabbing end-of-the-tether quality to the Act One finale (“Welcome to the edge, the verge, the ledge”) where Greig, in specially trained and remarkably serviceable voice, is joined by the rest of the teetering brigade.

And Haydn Gwynne is bliss as the bonkers Lucia, a mad Fury swathed in the 1960s outfits (including a lunatic pink Jackie Kennedy number) that pre-dated the incarceration caused by her husband's desertion, but hauntingly communicating in “Invisible”, which is the best song of the evening, the tragic price she has paid for this long suspension of time.

Preparing the notorious gazpacho, Greig has a theatrically self-conscious Ophelia moment (“There's rosemary, that's for remembrance”) and the emotional truth and pertinence pierce your heart before she then tips in an avalanche of valium.

The sense that, as well as being useful for prostrating policemen, the potion becomes a Midsummer Night's Dream-like transformative elixir is heightened here at the glowing close. I think it's no wonder that Almodovar has given this exhilarating version his blessing.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments