The Gods Weep, Hampstead Theatre, London

Boardroom blitz ends in tears

King Lear asks many searching questions, often explicitly. One of the most profound of these is "Is there any cause in nature that makes these hard hearts?". In our post-Darwinian times, where some find it hard to fit the concept of altruism into the allegedly "selfish" scheme of natural selection, the equivalent question would more likely be "Is there any cause in nature that makes these soft hearts?"

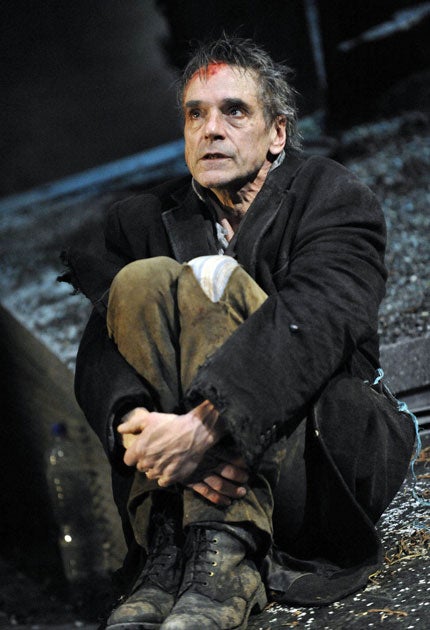

Produced by the RSC, The Gods Weep is a contemporary "response" by the talented dramatist Dennis Kelly to Ran, the great Kurosawa film that itself is a response to King Lear. But the main query the piece provokes is somewhat more parochial – namely "why in heaven's name has the RSC not given Kelly more help in achieving creative mastery over so self-indulgently swollen and flailing a play?" Instead, they've thrown a large cast, a handsome budget and a star name (Jeremy Irons) at it.

The opening scenes are promising. Colm, Irons's Lear avatar, is the head of a huge company. He's started to have panic attacks and he thinks it may be time to draw in his corporate horns so he divides power among his subordinates. The boardroom is, of course, a snake pit waiting to happen. The sickest of the suited demons, Richard (Jonathan Slinger) keeps consulting a business-based astrologer but you don't need her to tell you that the new financial initiative – of buying up land in poor regions of the world in order to lease out to rich nations – is going to fall foul of the twisted personal battles between the new CEOs.

It's not just existence that hurtles downhill when the repellent Richard brutally breaks Colm's arm on the boardroom, ushering in wild civil war scenes. The play – and Maria Aberg's emotionally hollow production – also take a decided turn for the worse. There are atrocities galore but they develop into a pattern of risible predictability. You learn to disbelieve in all gestures of apparent tenderness for they tend to turn out to be tricks disguising murderously violent intent. When Richard drags off Helen Schlesinger's rival CEO by the hair, I took a small bet that he would re-emerge with his face triumphantly smeared in her blood. He duly did. And it's quite shy-makingly unshocking, because it's just so easy to bring about theatrically and human degradation is not quite the news it was in Shakespeare's day. May I suggest that all playwrights and directors who want to deal with atrocity responsibly and illuminatingly read Anthony Hecht's piercingly brilliant poem "More Light! More Light!" (about a shocking real-life death-camp incident) before starting rehearsal?

The writing has serious problems patrolling the divide between intentional comic bathos and the less scheduled variety. The stricken Colm seeks out the daughter of the man he once ruined and there are partially affecting final scenes of mutual survival in the forest. Irons is genuinely touching when he says to the girl: "I don't deserve forgiveness. Forgiveness would break my heart." But when he wakes to her for the first time and asks, Lear-like, whether he's posthumous, her reply "You're not dead, Bob, you're just not well" is typical in the pointlessly uneasy audience laughter that it prompts. In his portrayal of the early explosive disorientation, it's sometimes hard to decide whether the uncertainty is the character's or the actor's, but Irons finds form in the later batty, whimsical wit and tentative tenderness of Colm.

The play could be subtitled "The Stuffed Menagerie", so many non-human creatures are drawn to our attention. But again, rather than the Shakespearean monsters of the deep, they are jarringly half-jokey like the corpse of the cat that Colm killed in his car and totes around in a case. When granted a miraculous second lease of life, this moggy (wiser than the first-night audience at Hampstead) let itself out of the bag and scarpered as fast as its little legs would carry it.

To 3 April (020 7722 9301)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks