Six Degrees Of Separation, Old Vic, London

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.We are getting a double helping of the paintings of Mark Rothko in the London theatre at the moment. Red, at the Donmar Warehouse, takes us into the great abstract expressionist's New York studio. And now in David Grindley's stunningly well-directed revival of the 1992 John Guare hit, Six Degrees of Separation – a piece in which the central couple of moneyed Manhattan-ites own a double-sided Kandinsky painting that twirls aloft – the designer, Jonathan Fensom, has had the inspired idea of wrapping the proceedings in the surround of a curving Rothko-esque wall.

With its bars of luminous, almost thermal blood-red, this structure has the effect of turning the stage into a corrida. It's a brilliant way of bringing out how there is a kind of barbarism (cultural, marital, financial) always poised to spring from under the sleek surface of a world that the global recession has, by now, dated. Rothko had a notoriously conflicted attitude to his rich buyers; his stomach would have performed a half-somersault at the sacrilege of being, spectrally, part of the furnishing in the apartment here.

The play takes wing from the real-life case of the young black impostor who wormed his way into the hearts and bank accounts of wealthy New York families by claiming to be the son of Sidney Poitier and a college friend of their kids. It's often very witty, not least about what passes for wit and knowing art-chat amongst these people. But the production understands how the play – with its presentational devices, its non-chronological revelations about the black boy's background and widespread effect – constitutes a kind of darkly comic psychomachia via which a whole way of ostensibly well-meaning liberal life is placed under the microscope.

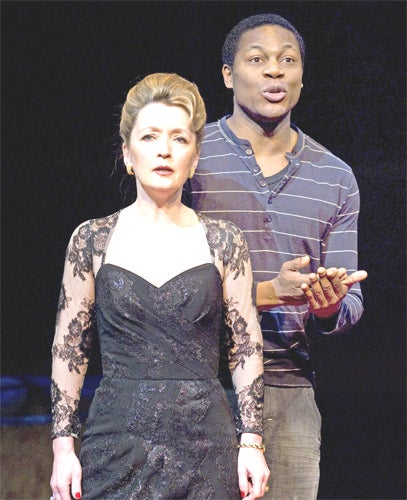

The acting is extraordinarily fine. Lesley Manville superbly captures the brittle hostess's brightness, while letting you see flashes of the underlying loneliness which draws her to the intruder as if to a life-line. Her manner reminded me of the great Cole Porter song of a socialite's sadness, "Down in the Depths (on the Ninetieth Floor)". As her husband, Anthony Head is bursting with a demonstrative energy that is designed to distract the character and others from his awareness of seeping bad faith (he's so busy juggling deals with the Japanese and with a pre-revolutionary South African white that he has no real time to "love" art).

"Paul", the young black man who adopts the false identity, is portrayed with great skill by Obi Abili. The actor has a tricky job because, until the marvellous scene where we see the character trading sexual favours for the secrets of his address book with a hapless gay student, he is seen only in the various guises by which he second-guesses what the Manhattan-ites want from a supposedly well-connected black stranger. Abili slightly overdoes the command with which, after descending on them as a "mugged" victim, Paul takes charge of the evening. Or maybe he should emphasise more how this young man is severely bipolar. But by the time we see him cruelly hoodwinking a hard-up pair of naive Utah-born students with the sense of rapturous possibility he's adept at transmitting, Abili is thrillingly on-song.

The character, who disappears through the net of the legal system into possible suicide, tailors himself as a projection of the well-heeled folks' desires. But is he also, in the sense that we never see him alone or "explained", a semi-sentimental projection of John Guare? The real-life prototype notoriously sued Guare for plagiarising his life. Like the character himself, it all shades off into the imponderable. But that, I'd argue, is what gives the play its mysterious power. Certainly, this rigorously assured revival make one feel that hitherto we have underestimated Six Degrees.

To 3 April (0844 871 7628)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments