The Night of the Iguana, Noel Coward Theatre review: A brave, magnificently modulated revival

Starring Clive Owen and directed by James Macdonald, this is a brilliant reminder of what an extraordinary feat Tennessee Williams pulled off here

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In 1964, John Huston directed a movie version of this Tennessee Williams play, which premiered in 1961 and proved to be the great dramatist’s last commercial success on Broadway. On celluloid, Richard Burton played the former Episcopalian minister (now at the end of his rope) who has been defrocked for blasphemy and for having a taste for underage girls. The buccaneering director recreated the play’s vibrantly seedy Mexican setting by descending on the somnolent beach town of Puerto Vallarta. Burton’s soon-to-be wife, Elizabeth Taylor, visited the set – followed closely by the world’s press.

The original play is rarely revived (Woody Harrelson played the hard-drinking errant Reverend T Lawrence Shannon the last time it surfaced in the West End). But now, James Macdonald’s magnificently modulated revival at the Noel Coward Theatre is a brilliant reminder of what an extraordinary feat Williams pulled off here. The production is quiveringly alive to the play’s artful collision of mad, black humour and deep delicacy of feeling. It’s brave to be mounting it at a time when we are all on guard about attempts at empathy for predators.

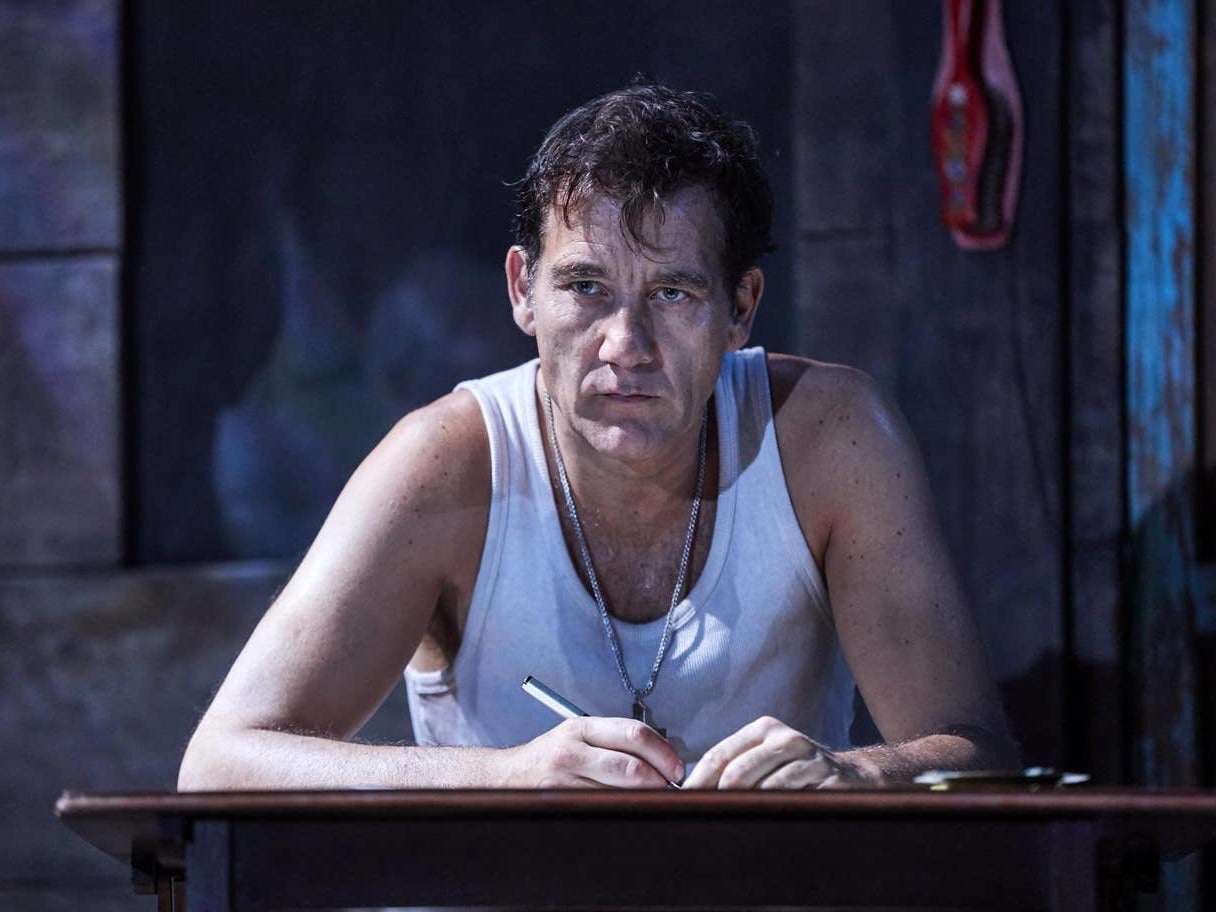

The Reverend is performed here by another actor predominantly known for his screen appearances – Clive Owen. But Owen, in his widely spaced appearances on the boards, has shown serious stage chops. Here, he takes you right inside both the sensitive and the farcical sides of Shannon’s spooked crack-up. Hair and crumply linen suit matted with sweat, he is an Orestes figure reduced to acting as a low-rent tour guide; his version of the Furies is the group of female Baptist school teachers who are unsurprisingly affronted when he impounds the ignition key of their bus. The women are forced to spend the night in a colourfully raffish hotel run by the raunchy, newly widowed and cash-strapped Maxine (performed by a very intelligent, stereotype-tweaking Anna Gunn).

The play is set in 1940. The stage is a traffic snarl-up of well-oiled, obdurately cheerful members of a family of Nazi-sympathising German tourists, alongside a pair of Hispanic houseboys. Most Shannons are butch and beleaguered; Owen’s bonier beauty registers the character’s despairing, neurasthenic spasms with more feeling. As he demonstrated in A Day in the Death of Joe Egg, his last West End appearance, he has a fine instinct for turnings into a manic, bitterly vaudeville-style Master of Ceremonies. That talent serves the Shannon role very well.

We never get to see or hear from the infatuated 16-year-old Charlotte (Emma Canning) – a pity, because of all the 20th century male American dramatists, Tennessee Williams would have risen to the #MeToo moment with the most fellow feeling. Owen’s Shannon thinks of these girls less as people than as figments of a personal self-disgust that drives him to lash out with post-coital violence.

Within the particular economy of this play, Williams is more intent dramatising the contrasts and affinities between the different side of his own soul. Shannon is who he feared he was. Hannah Jelkes – the itinerant watercolour and staunch protector of her poet-grandfather (brought to life by the fantastic Julian Glover) – represents what he wished he could be. Played with a luminous, challenging patience and dry humour by the superlative Lia Williams, Hannah is the embodiment of how to live beyond despair and still live.

Breathtakingly well done here is the sequence where Shannon and Hannah have what can only be described as the spiritual equivalent of a one-night-stand. Trussed up in a hammock, like a trapped and netted iguana, Owen thrashes around with desperate self-pity; in an equivalently calm ceremony, Williams reaches out to him by preparing a drink of sedative poppy seed tea. They recognise that they are both damaged hustlers. Sometimes achingly funny, sometimes, well, aching. This is a wonderful evening.

To 28 September

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments