King Lear, review: 'Sam Mendes and Simon Russell Beale's production is worth the wait'

Olivier, National Theatre, London

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Simon Russell Beale was not gushing when he described Sam Mendes as his “professional soulmate”. For close to a quarter of a century, the pair have brought out the best in one another. Their collaboration on King Lear has long been in the pipeline and I am delighted to report that this production was well worth the wait.

Staged in the vast Olivier, it's a powerfully searching account of the tragedy that fuses the familial and the cosmic, the epic and the intimate, and ponders every detail of the play with a fresh, imaginative rigour.

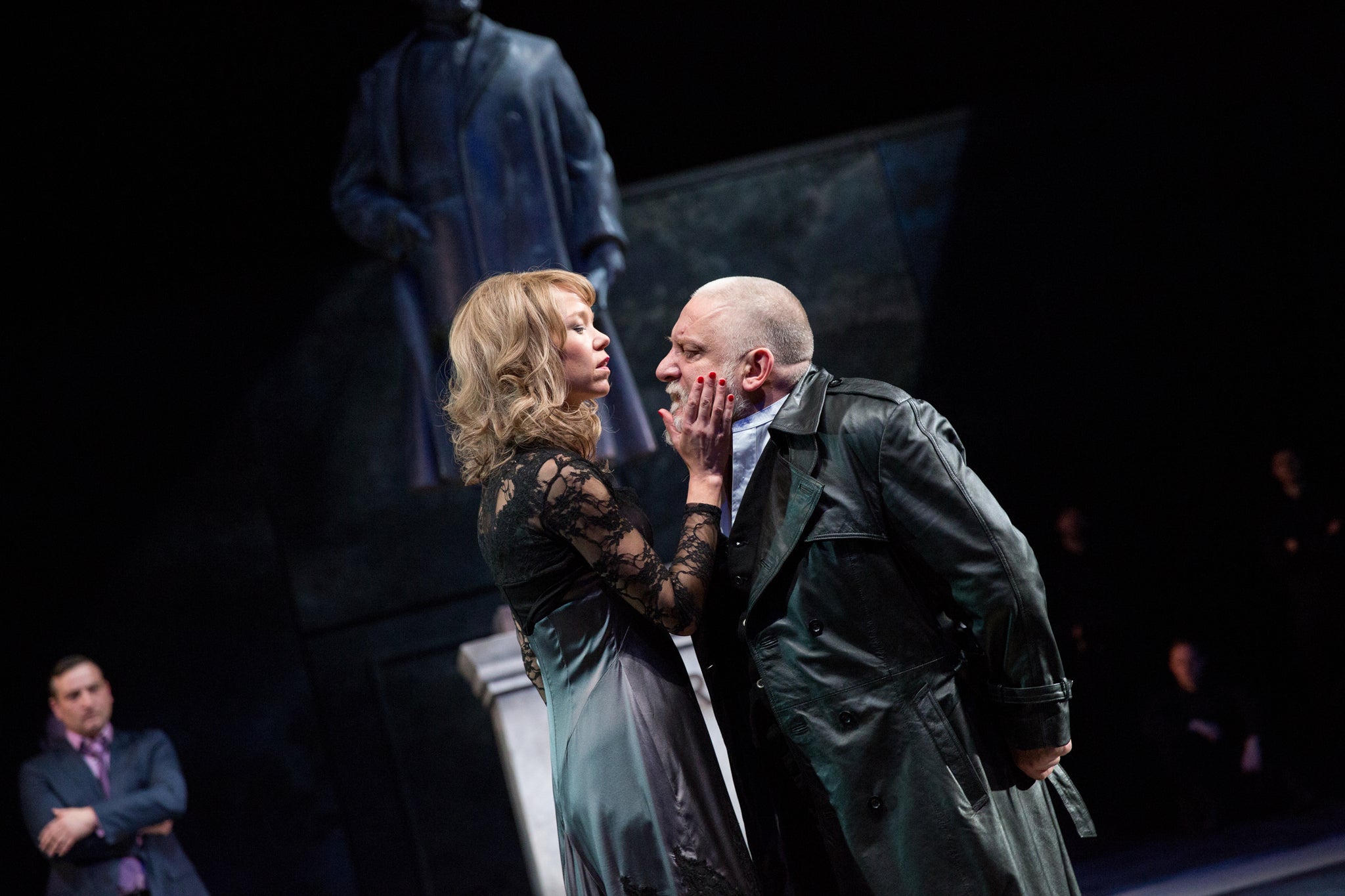

Mendes has set the piece in a present day totalitarian state. Russell Beale's Lear is an old Stalinesque despot, surrounded by a huge armed guard, and the love-test of his daughters is a chilling public ceremony, with microphones, designed to prop up his ego before he delegates power.

As vehemently performed by the excellent Olivia Vinall, Cordelia's refusal to play the game sounds like a principled protest against a regime based on conformism and flattery.

Russell Beale brilliantly shows you that the King's paroxysms of furniture-overturning fury are an index not just of Lear's deteriorating mental state but of his frightened awareness that his brain is failing and desperate need for reassurance. Hence his psychological dependence on keeping his train of knights – a huge group of rowdy soldiery here whom the daughters see as a potential political threat and are reluctant to entertain, understandably given that their behaviour includes dumping a whole dead stag on Goneril's dining table.

It's a mark of how closely the production follows the implications of becoming powerless that even a group of the knights who have not been axed are seen deserting the ex-king and sneaking off up the central aisle.

Adrian Scarborough's excellent Fool is a melancholy music hall comic in a check suit and feathered trilby, full of oblique, subtly anguished concern for his master. Why he disappears from the play is explained by a shocking twist that I won't disclose but which is horribly plausible in a production that refuses to sentimentalise the hero.

Russell Beale can break your heart with the mad Lear's sudden moments of piercing clarity but his superb portrayal of man who discovers the folly of a life predicated on power rather than love remains turbulent with complexities and contradictions. Padding agitatedly around in a hospital gown in the reunion with Cordelia, he has to fight with his scalding sense of shame for what he did to her before he dips confirming fingers into her tears and tastes them. And in the last scene, he delivers the line “Look on her, look, her lips” not in a dying delusion that she lives but in an angry, almost dogmatic final outburst against the meaninglessness of the universe.

There are one or two misjudgements – not least the hydraulic ramp that hoists Lear and the Fool into air for the storm sequence and looks like a special effect in a West End musical. But the production is, for the most part, thrillingly well-played – especially by Anna Maxwell Martin whose Regan is a posh nymphomaniac turned on by torture and by the luminous Tom Brooke who brings out the naïve, improvisatory nature of the way Edgar plays Providence in his father's life. Strongly recommended.

To May 28 – NT Live broadcast in cinemas May 1; 020 7452 3000

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments