Hamlet, NT Olivier, London<br/>Hamlet, Crucible, Sheffield<br/>Enlightenment, Hampstead Theatre, London

Two star-name Hamlets at once was bound to invite comparisons. Simm's Prince was patchy, but Rory Kinnear was superb

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It's getting to be like that scene in Spartacus.

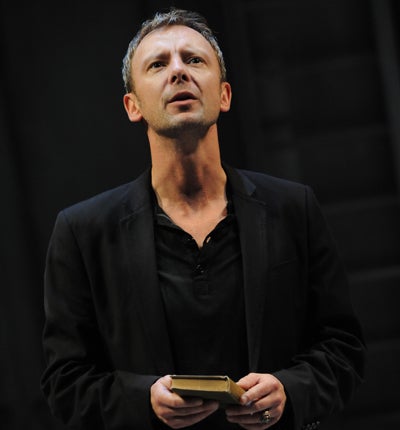

"This is I, Hamlet the Dane." "No, I am Hamlet the Dane." "No, I am ..." How many Princes of Denmark can there be? We had Jude Law, last year, following hot on the heels of David Tennant: both scintillating. There was Jonathan Miller's Bristol staging as well, which made Jamie Ballard's name. Now here come two more stars – the NT's Rory Kinnear and John Simm at the Crucible.

Yet the role is so infinitely mercurial, the variations are what's fascinating. Certainly, Nicholas Hytner's modern-dress Hamlet at the NT proves gripping and full of sharp insights.

In the grey neoclassical chambers of Elsinore, the regime run by the usurper, Claudius, is rife with surveillance and image conscious speech-making. Patrick Malahide's lean and sleek-suited Claudius, looking uncannily like Vladimir Putin, is a calculating bureaucrat with military backing. Armed security men, with earpieces, hover in every doorway – no sustained privacy allowed.

In his head office, Malahide delivers his first royal pronouncement – on marrying his brother's widow – as a stage-managed public broadcast. He smooth-talks, to camera, while Gertrude (the ever superb Clare Higgins) smiles awkwardly at his side – screeching with relief and grabbing some champers as soon as it's a wrap.

Kinnear's bereaved Hamlet stands in a corner, shocked and fuming, though neatly dressed (black suit, white shirt). When he speaks out – his escape back to Wittenberg University having been thwarted – he is caustic. When alone he fights back tears.

This actor doesn't have the lithe sparkiness of Tennant, but he can be explosive and is always penetratingly intelligent. His lunacy is clearly a mocking act, switched on and off. At the same time, those antics spring from depression as he plays suicidal with Polonius, rising from his unmade bed like a ghoul, wrapped in a duvet. Alone, his philosophising is quietly, brilliantly lucid as he thinks through "To be or not to be," occasionally puffing on a cigarette.

Though Hytner and others have staged Elizabethan political dramas with contemporary suits and televised broadcasts before now, this Hamlet is often cleverly innovative. His cast work closely on their lines, and between them, to add twists and explore how far the totalitarian culture might impinge on these private lives. So David Calder's Polonius has had Ruth Negga's Ophelia and Hamlet under observation. He waves a file of photographs at his mortified daughter. When she goes troublesomely insane, we see her surreptitiously purged by Claudius's henchmen. Therefore Gertrude's poetic account, to Laertes, of his sister's drowning is an elaborate cover-up, uttered under pressure with Higgins shooting bitter glances at Claudius and slugging whisky. Some of these novel takes are strained, and not all the supporting roles remain strong. Considerable tragic poignancy is lost too, as this Hamlet is more livid than loving toward his womenfolk. But all in all, outstanding.

In contrast, John Simm's Hamlet is most touching in his tenderness towards Michelle Dockery's Ophelia, kissing her as if forgiving her paternally enforced aloofness without a second thought. In other respects he's less electrifying, and Paul Miller's slow-moving production – similarly in modern dress and set in a grey neoclassical palace – is no competition for Hytner's.

Simm's verse-speaking skills are respectable, though, and his high-pitched voice makes him sound as if he's still an angst-ridden youth. Yet it's neither endearing nor persuasive. The problem is that his emotional intensity comes and goes. Every so often he burns brightly, with flashes of loathing and despair.

His philosophical soliloquies – delivered to the audience, holding a book – hover between heartfelt confession and mini-lecture. Woefully, however, Dockery's delivery is terrible: rushed, flat, nothing heartfelt, mere words, words, words. Barbara Flynn's Gertrude has none of her counterpart Higgins's rich detailing, though John Nettles's Claudius is more interesting than the arid Malahide, being expansively affable and amorous, only gradually worn down – by Hamlet's hostilities – to reveal his nasty side. By the way, there's another big-name Hamlet on the horizon. Michael Sheen next year at the Young Vic.

Meanwhile, Enlightenment marks a new dawn for Hampstead Theatre, after a pretty dismal patch. This new play by Shelagh Stephenson is the first production by the venue's new artistic director and potential saviour, Edward Hall. Alas, it seems we'll have to hold out a bit longer for a blinding success.

Stephenson's scenario sounds engrossing enough. The 20-year-old son of a British, middle-class couple has vanished into thin air. He went backpacking, and they've heard nothing for months. He may have been kidnapped, fallen down a ravine, or chosen to disappear. His mother, Julie Graham's Lia, is grief-stricken and increasingly irrational, drawn in by a psychic (feeble comedy) and an even more morally suspect documentary-maker (caricatured conniver).

The young man who eventually returns is mentally damaged and there's at least one sociopath under Lia's roof. Enlightenment does, belatedly, develop into a disturbing web of lies. But Hall's white ovoid set with electric-blue lighting hardly generates domestic authenticity. When Stephenson's characters discuss liberal guilt, her dialogue often sounds like a string of authorial jottings: "There's a Bermuda triangle where materialism and capitalism meet the fatal concept of good taste" and so forth. Worse is Lia's appended analogy from physics, the theory of non-locality about diverging particles: a dire case of science superficially applied.

'Hamlet' (020-7452 3000) to 27 Oct then touring in 2011, it will be broadcast in participating cinemas on 9 Dec; 'Hamlet' (0114 249 6000) to 23 Oct; 'Enlightenment' (020-7722 9301) to 30 Oct

Next Week:

Kate Bassett hangs out with Aristotle Onassis in a new biodrama

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments