DESH, Sadler's Wells, London, review: Akram Khan's own dancing is extraordinary

This solo work created in 2011 by choreographer and performer Khan is his most personal yet

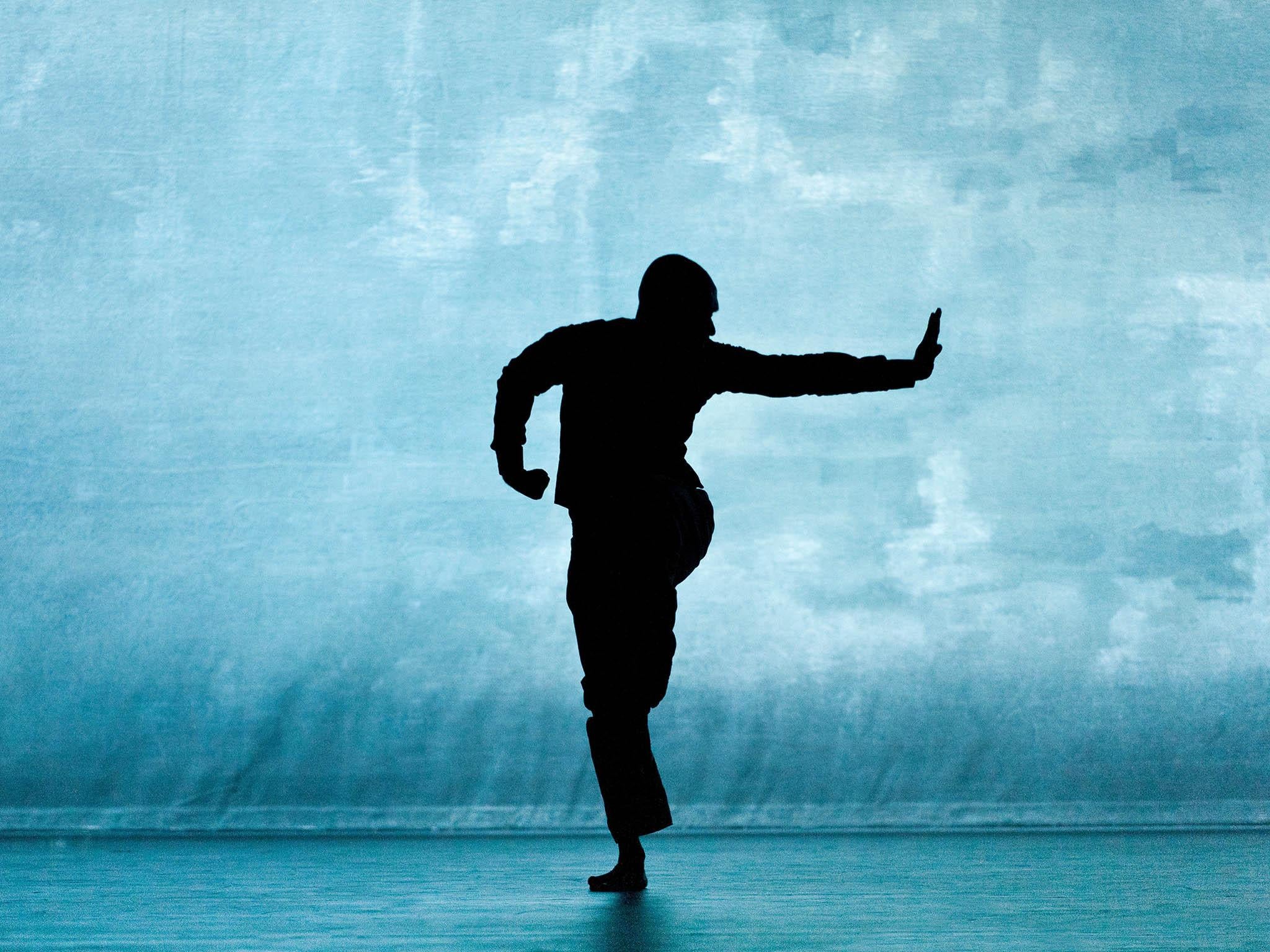

Akram Khan’s DESH is spellbinding. Created in 2011 as his first contemporary solo show, it’s an entrancing mix of storytelling, myth and family dynamics, conjuring worlds and then asking them hard questions. Lyrical and tough, it returns to Sadler’s Wells for its final performances, a well-earned victory lap.

DESH starts with Khan’s own roots. Born in Wimbledon of Bangladeshi origin, he trained in the Indian classical style kathak and in contemporary dance, making his name as a superlative performer and choreographer in both. In one scene, he remembers clashes between teenaged Akram and his baffled father, who doesn’t get why he needs to practise so much. His dances are a blend of classicism and Michael Jackson, his speech full of pop songs and a Northern accent he’s picked up from a soap opera. The family in DESH is a fictionalised version of Khan’s own. It starts with the imagined death of his father, the recognition that the stories he pushed away will one day be beyond his reach. The Bangladesh he goes back to isn’t the place of his father’s tales. He dances through the traffic of a gridlocked city, swerving away from cars and pedestrians, a single body peopling the whole stage. Ringing a call centre, he’s another rich westerner, complaining to a child worker about his phone. When he calls back, he tries to claim a sense of friendship that the child just doesn’t recognise.

Playing with his young niece, Khan wants her to engage with Bangladeshi folk tales – he’s disconcerted when she insists that “the biggest forest in the world” must be in Wimbledon Park – but shocked to find she knows about the war with Pakistan. Respecting his origins, he wants to idealise them, only to find painful facts intruding. In Tim Yip’s ravishing designs, a video forest blooms around Khan, before a tank rolls in among the trees and animals.

Khan’s own dancing is extraordinary. He goes from evocations of family life to a world of gods and goddesses, from anger to sweetness. He transforms himself into a touching, comic cook, his shaved head tilted forward with a face drawn on his scalp. Later we realise that this is his father; later still, that this man was tortured. Put under pressure, each image becomes richer and more complicated.

The world has changed in six years: DESH was made before the pressure of Brexit. Seen again, its exploration of identity, of politics as it impacts on family life, is as powerful as ever.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks