Boy Blue Entertainment, Blak Whyte Gray, Barbican Theatre, London, review: It's strict, bold and brilliant

Olivier award-winning East London hip-hop dance group, Boy Blue Entertainment, perform an abstract triple bill with new work and ditch the narrative

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Boy Blue’s new show Blak Whyte Gray is strict, bold and brilliant. The east London hip-hop group made its name – and won an Olivier award – with sharp moves and big, bold storytelling. This time, however, the company leaves narrative behind, with a programme that explores identity through fiercely distilled dancing.

Blak Whyte Gray is a triple bill, but each work leads into the next, developing moods and themes. Boy Blue’s directors, choreographer Kenrick “H2O” Sandy and composer Michael “Mikey J” Asante, keep the focus tight, with stripped-down staging.

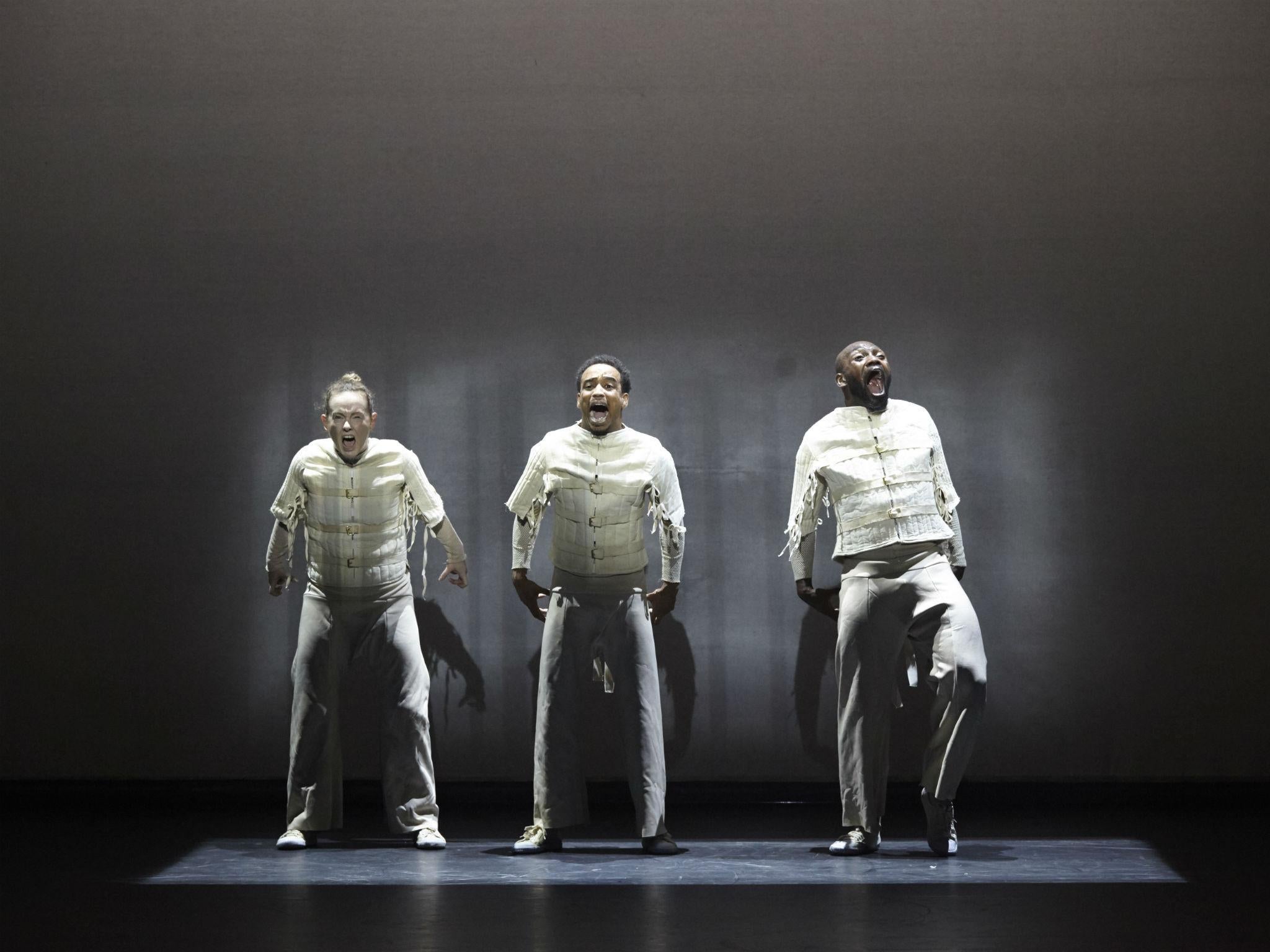

In Whyte, three dancers stand in a square of light, twitching through robotic moves. Ryan Dawson Laight dresses them in boxy white, with padded detailing and buckles that suggest both formal dress and straitjackets. Ricardo Da Silva, Gemma Kay Hoddy and Dickson Mbi dance with crackling precision, bodies pulsing to the distorted soundtrack. When they circle from the hip, they look fluid and jerky in the same moment, both united and trapped by their shared movements.

In Gray, Lee Curran’s lighting design expands the box into a broader grid. If the first trio were robots, the eight dancers of Gray suggest soldiers. There’s a military edge to the costumes, while the dancing has a pumping aggression, with movement driven from the chest and gestures that suggest preparing and firing guns. Yet the cast never lose their hip-hop fluidity, an ability to twist a four-square action into something unpredictable.

After these images of control and discipline, Blak explores struggle and transformation. The group holds one man up, arranging him in a heroic pose. As soon as they let go, he falls, only to be caught and rearranged. At last he learns to stand alone, following the group’s lead.

Blak suggests the creation of a hero by a community: he learns his authority from the people who hold him up. A red cloth is brought on and draped around him, like a toga; markings are painted on his face and torso. They shine brightly under UV lights, which also show up tribal patterns on the masks lowered from above. The final dances are influenced by African moves, adding a new freedom to the tight hip-hop steps.

Blak Whyte Gray is packed with images of power, of constraint and release. Without literal storytelling, there’s political bite to its pictures of strength and community, identity and change.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments