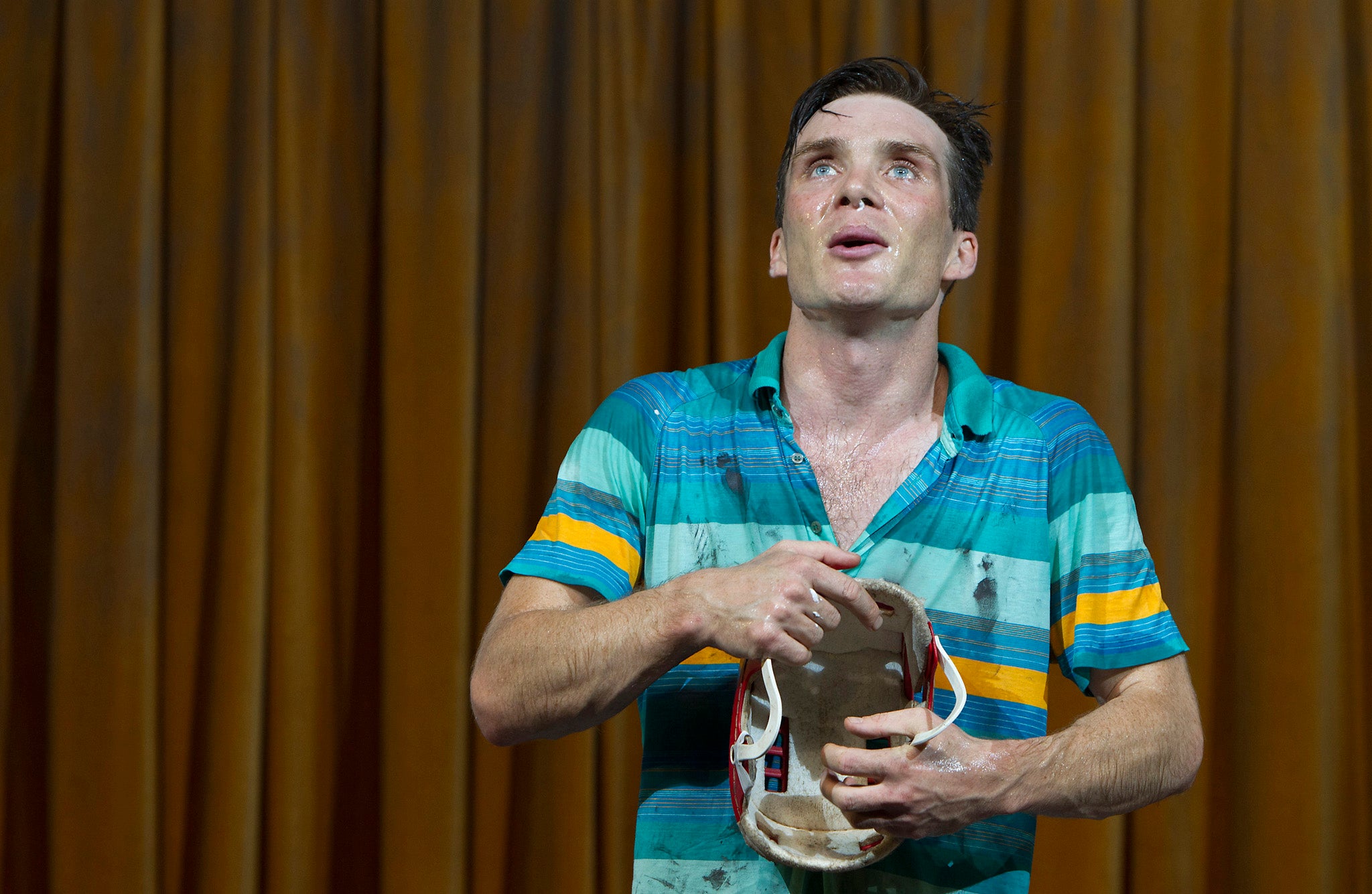

Ballyturk, National Theatre, review: Cillian Murphy is exhilarating to watch

But at several frustrating moments this work feels pointless

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.So, what's Ballyturk all about? Frankly, dear reader, I don't give a damn. Or rather, I've given up trying to figure it out.

The plot, devised in workshop sessions by writer-director Enda Walsh and cast members Cillian Murphy and Mikel Murfi, seems to be a sort of cruelly puzzling joke designed to torment the audience with cryptic messages about death, the power of imagination, making one's mark on the world, the trials of the artist's life and other existential issues, without ever really getting to the point.

In a peak of head-wracking desperation, I thought it might even be about bunnies (they do mention bunnies, malevolent ones, and flies) and how they live their fleeting lives to the full by packing so much into them, and how this should be an example to us all. But then again, no.

Writer-director Enda Walsh is known for locking his characters into airtight rooms where the real world is just a vague and distant notion, and Ballyturk is no different. Murphy and Murfi play two unnamed characters, racing maniacally through the day with a bizarre routine of dressing, undressing, dancing to power ballads, bursting red balloons and playing characters from their imaginary Irish town of Ballyturk.

There's a Beckettian quality to their exchanges — asking his friend to jog his memory, Murphy demands: “tell me something of no importance and the word will come to me, guaranteed.” But instead of waiting for Godot, or waiting for anything, they seem mostly content in their bubble, afraid, even, of what the real world might bring — and there's a childish, fraternal chemistry between them that's very watchable.

The set design by Jamie Vartan is brilliant. It's a brutalist grey concrete room, with a fake stage on the back wall, which later opens onto a “real world” outside. The stage-on-the-stage is framed by vomit-yellow curtains and filled with little scratchy pencil drawings of the Ballyturk characters' faces, like an audience watching us. The actors make good use of the dark wooden furniture fixed to the walls, by slamming into it and clambering over it.

The most remarkable thing about the duo, in fact, is their astounding energy. Mikel Murfi reels through an impressive performance of different Ballyturk characters with artful physicalisation and dramatic vocal gear shifts; it's like watching a drastically speeded up audition tape.

While Murphy flings himself across the stage like a demented Puck — twitching on the floor, bashing his head on a wall then leaping gaily onto a high shelf. It's exhilarating and exhausting just to watch him. The rumour is that he was so enthusiastic in rehearsals he managed to smash a wardrobe to shreds.

There's poignancy in the play, like when Murphy falls into a fit and Murfi silently takes him into his arms, calmly waiting until it's over, or when Stephen Rea appears as an enigmatic, chain-smoking visitor (is he Death? God? Murphy's character's father? I give up) and speaks poetically about the briefness of life and the need for “laying down legacy”.

There's humour too, in the elaborate Jenga tower of biscuits, brought to appease Rea's formidable character, or the surreal running joke about bunnies having five legs.

But without a clear plot to anchor them, these moments of humour and sadness feel like a match lit in a vacuum, they spark and vanish and don’t catch light. Murphy's character says in the final scenes, “there's no life to it. It's filling the room with words.”

At several frustrating moments, this work feels just as pointless.

September 16 – October 11; 020 7452 3000

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments