Philip Ridley on how to combat Donald Trump, his love of Jude Law, his new fantasy play Karagula and how he’s fascinated by other people’s conversations

Philip Ridley's latest work is a dark assessment of modern culture, set in a fantasy world similar to 1950s America. He tells Emily Jupp why he find the modern world terrifying

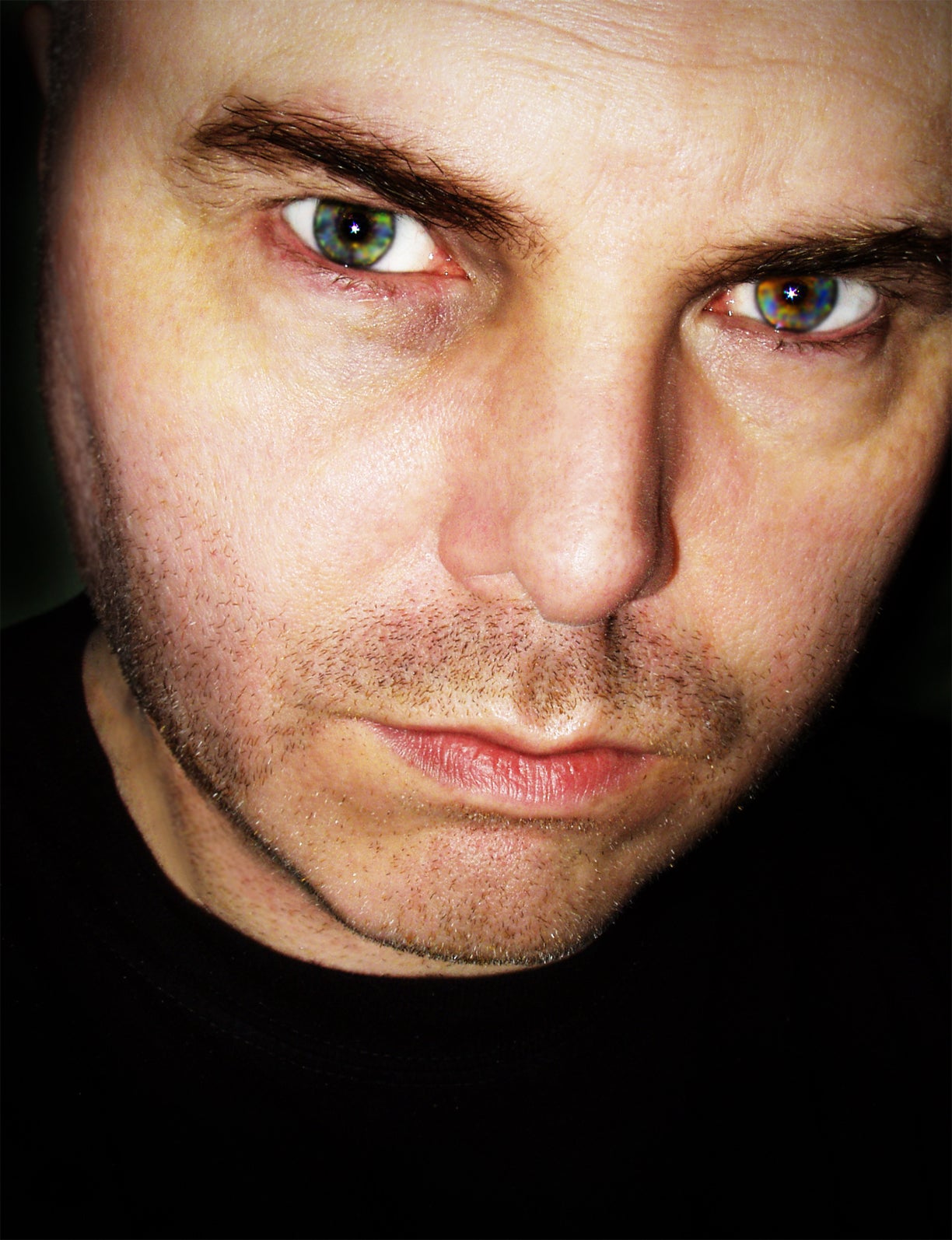

Philip Ridley, 51, is one of Britain’s greatest living playwrights (although he might squirm if you said that to his face, as he is relentlessly modest). He is the only person ever to win both the Evening Standard’s Most Promising Newcomer to Film and Most Promising Playwright awards. He crashed onto the theatre scene in 1991 with his controversial debut play, The Pitchfork Disney, which altered the course of theatreland and which is now published as part of the Methuen Drama Modern Classics range, recognising it's huge impact on British theatre. Aside from several ground-breaking plays which surprised and shocked critics with their uncomfortable versions of modern society, Ridley is also an artist, painter and film-maker. He studied at St Martin’s School of Art and Design and identifies with the YBA movement, being a contemporary of Damien Hirst and the Chapman Brothers. His new work, Karagula is a vast theatre project with a cast of 70 characters, set in an Americana fantasy world. The Independent caught up with him the week before Karagula opened.

Where are you?

At my mum's, in Hackney. You can’t get Wi-Fi or signal here. There is just one small area that has mobile signal and I am standing in it.

And where are you living now?

In Ilford, I moved two years ago. I needed more space to do painting in. I am going to build a shed at the bottom of the garden but it is just finding the time to get things done... I moved about 18 months ago and there are still boxes that I haven’t unpacked. I had been living in Bethnal Green since I was a student and every project gives you about six boxes of stuff, so it had accumulated and I was living in what was basically a store room. When friends came round I had to give instructions as to how to navigate it all.

Tell me about your workspace, pre-shed.

I tend to completely cocoon myself with a piece of work and I have one back room here with charts and images for the project I’m working on. People know when I go into that cocoon that they won’t see me for three months. You get immersed in it. You start in spring and when it ends its already winter. You need to not panic. I do panic though. It’s amazing how much fun you can have by yourself, but the thing is I am not by myself. As a writer you have to crave solitude, because you’ll ever create anything otherwise, but I am the least lonely when I am writing because I know those characters inside out and I am surrounded by people I know and empathise with, but in the real world I don’t have that, I don’t know anyone in real life as well as I know my characters.

Details are scarce but from reading around, it sounds like your new play, Karagula, will be a cross between The Hunger Games and Star Wars with a touch of The Drowned Man thrown in. Am I wrong?

Yes, you are. It is not that kind of thing. I didn’t sit down and think I was going to write an epic. I don’t plan and I never know where anything is going I have always worked like that, I just let the work tell me what it wants to. I teach, and I tell my students you can’t pre-judge where your ideas come from, you have to just live as intensely as you can and something will hopefully spark or build up. Don’t pre-empt where inspiration comes from.

The fantasy format is a way of saying something about the world around us but it’s a way of doing it by not directly naming anything. It is not Star Wars, even though that quite appeals.

And there are two moons in this world?

The first real scene you think you’re in 1950’s Americana and you are in that high school world and there is a clue that is slipped in, where one character says “oh look both moons are full,” but the rest of the world is as you might expect. It’s only as the play progresses that you realise the world is very different from ours.

What does it have to say about the state of the real world?

We have entered a period where the world is astonishing and terrifying and one thing Karagula deals with is that the old world doesn’t apply any more and as an artist that is very exciting. The play is questioning how you deal with the emergence of Donald Trump, for example, because he is not playing by the usual rules of human etiquette. How can you rationally and intellectually react to something that isn’t intelligent or rational, like Trump? How do you combat that? So it’s a strange and chaotic world that we inhabit.

You imagine that the court of Caligula must have been similar; how do you react when an emperor brings his donkey into the Roman Senate?

Karagula opens on 10 June, so are you just putting on the finishing touches?

I’m going in and polishing and reshaping and cutting and it is really scary! We are in the final week now. I am talking to Max Barton, the director, about the changes and I will do that up to the wire and through the wire as well, because you don’t know what you’ve got with a stage play until you have an audience. There are some things you think you need to hammer home to make your point but then the audience understands it in a couple of seconds and you don’t need to clarify it, so it is a process of storytelling clarity. Then if they don’t like it, that’s fine but at least they are seeing it the way you intended. It is very different from making a film which is kind of fossilised but theatre requires an audience in the way other art forms don’t require one. The paint on a canvas doesn’t change because of people looking at it.

Most of what you write is set in the east end of London. Why did you decide to set Karagula in a parallel world? You aren't bored of London, are you?

No, I don’t think it means that but a friend said to me a while ago that “a lot of your plays are quite fantastical but you can chart your biography in them” and the first play I wrote after I moved from Bethnal Green was Radiant Vermin, about a couple buying a new house, and for me, maybe in the back of my brain, moving out of Bethnal Green is like moving to another world.

You're working with a new theatre company, PigDog, for the production. Tell me about them.

They are really exciting. Max Barton, the Director of Karagula, directed Piranha Heights, my play at the Old Red Lion a few years ago and it was breathtaking. [It was nominated for Best Production, Best Director and best Set Design at the Off West End Awards]. I felt he really understood the work and he has a great visual and sound sense. Max has now founded PigDog with Shawn Soh and I think they are really at the forefront of change in new British theatre.

Who are the actors involved?

There are nine incredibly diverse actors; they are all new to me. [Theo Solomon and Emily Forbes are playing the leads]. It is the biggest number of people I’ve had in a rehearsal room for years. The nine actors are playing about 70 parts between them.

A lot of people you’ve worked with early in their careers have become household names.

Ben Wishaw wasn’t a known name, nor was Helen Baxendale or Jude Law. Jude Law’s first leading role on stage was on The Fastest Clock in the Universe and Viggo Mortensen was in The Reflecting Skin.

All those people that have gone on to be major talents, you could feel it the first time you clapped eyes on them. Jude Law’s audition for The Fastest Clock in the Universe will be one of the defining moments of my life. It was only my second play, so that style was new and Jude read a speech of Foxtrot’s and got the rhythm, the pacing, the feel of it spot on and suddenly the world felt less lonely, because someone else understood what I was trying to do.

Jude Law auditioned for my second play and got the rhythm, the pacing, the feel of it spot on and suddenly the world felt less lonely, because someone else understood what I was trying to do. Everyone knew then that he was one of the most talented actors of his generation.

Everyone knew then that he was one of the most talented actors of his generation. I adore actors, as you can probably tell, and to be in the presence of them is one of the most wonderful feelings in the world.

You have a wonderful knack for dialogue and I've read that you used to hide a Dictaphone under the sofa as a kid so you could listen to your parents’ conversations after you went to bed at night. Is it true?

I still blush with embarrassment at this but I must emphasise it was a long time ago, when I was 14 or 15, I wanted a reel-to-reel recorder as a Christmas present, it was a toy thing and you could carry it around, it was a lunch box size. I used to hide it under the sofa in the living room and it recorded for an hour. I used to record my parents’ conversation and write it up every night as a transcription, as though I was taking notes for Watergate or something.

Also I was ill when I was young, I suffered from Asthma and people used to monologue at me basically, because I couldn’t get enough air in to reply properly to them. I became fascinated by how Aunt Rita spoke differently from mother and my father spoke differently from my uncle Bill, and I became obsessed with that very early on and that is the start of drama; how a person reveals more about them than they realise, simply through their choice of words.

You're a polymath, working across art, theatre, film, everything. Have you ever thought you might be better off just focusing on one thing?

I have never seen it as different art forms. I am doing one thing, I am telling a story and sometimes you use different ways of telling a story so I can't say I prefer one form over another. It is our culture that feels a need to put a label on it. I don’t think art should be divided in the way I hope we don’t divide up gender and sexuality in the future. Having said that, with everything I do, people sit down, look at it and say "Oh God what is this?" and it makes it hard to sell.

When I did The Pitchfork Disney I wasn't part of that theatre world, I was an outsider and so my work was influenced by other things. I think the reason it caused such outrage was it appeared out the blue and wasn’t in the tradition of theatre work at the time or following the direction theatre was headed in.

Is there anything else you can reveal about Karagula?

We have to be a bit secretive because it’s a new play and it’s changing and morphing at the moment but also I quite like the mystery. I hope you enjoy it. I have pushed myself. I always think if I dare and scare myself then I have a chance of daring and scaring others.

‘Karagula’ by Philip Ridley is performed at a secret London location. Tickets available from www.sohotheatre.com or 020 7478 0100; £15 - £28.50; Friday 10 June – Saturday 9 July.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks