William Shakespeare: Experts 'deeply unconvinced' by claims that the earliest portrait of the Bard has been discovered

Country Life's editor had called it the “literary discovery of the century”

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Grandly presented to the world as the first known image of William Shakespeare to have been produced while he was alive, a 400-year-old drawing said to depict the Bard in his prime and with “film star good looks” has taken dubious scholars by surprise – not least because of its source.

Experts immediately raised doubts over whether a botanist writing in Country Life really had cracked a complicated Tudor code to make one of the most startling discoveries about the playwright in generations.

The commonly known likenesses of Shakespeare, found in the First Folio and his monument at Holy Trinity Church in Stratford, were both created after his death.

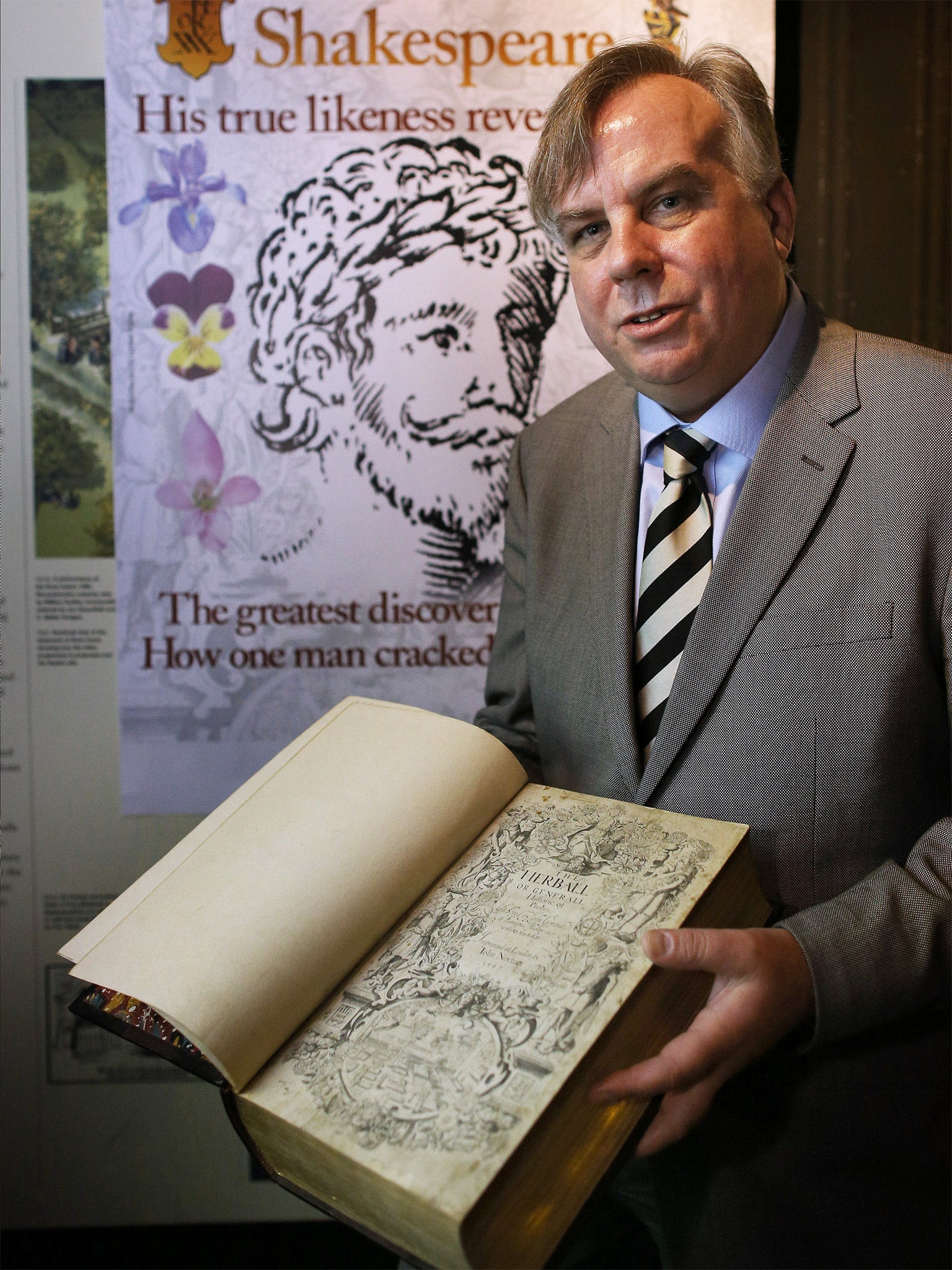

But Mark Griffiths, who also works as a historian, has claimed that he had discovered an image of the playwright made during his lifetime in a celebrated Elizabethan book on plants.

Just 10 first edition copies of John Gerard’s The Herball or Generall Historie of Plantes from 1598 – which first introduced the potato to a European audience – are known to survive with the elaborately engraved title page.

A handsome, bearded man on the right of the image is shown wearing a laurel wreath on his head while carrying an ear of sweetcorn in one hand and flowers in the other.

Around him are symbols and cryptic clues “of the kind loved by the Elizabethan aristocracy” that point to his identity being the world’s greatest playwright aged 33, Mr Griffiths said.

“We have a bunch of identifiers, the names of which are indisputable and unique to Shakespeare. We have basically a caption underneath, coded in the style of clever men of the time, which says William Shakespeare,” he said. “Drawn from life, in the prime of life, this is what he looked like. Finally we know what he looked like.”

Arguing that he had not taken assumptions about the picture too far, Mr Griffiths – who has spent five years testing his theory which had involved unlocking the meaning behind ciphers, heraldic motifs, rebuses and emblematic flowers – said: “It’s algebra, it’s a simple equation.”

He also claimed to have found new work by the playwright – a small entertainment commissioned by Queen Elizabeth I’s spymaster Lord Burghley – saying he will reveal more information next week.

Mr Griffiths’ argument may not have been helped as it was made in a magazine better known for its coverage of gardens in stately homes, but Country Life’s editor Mark Hedges called it the “literary discovery of the century”.

The claims were also supported by Edward Wilson, emeritus fellow of Worcester College, Oxford, who said: “It is sensational and we don’t think anyone will disprove this.”

Yet Shakespeare Professor Michael Dobson, director of the Shakespeare Institute, said he was “deeply unconvinced” by the claims, and called it a “hallucination”.

“I can’t imagine any reason why Shakespeare would be in a botany textbook,’ he said, adding: “I don’t think very many people are going to take this seriously.”

Lucy Monro, Shakespeare lecturer at King’s College London told the BBC the picture was “unlikely” to be the Bard, adding: “The idea you would have the writer depicted from life in quite this way, would be pretty much unprecedented.”

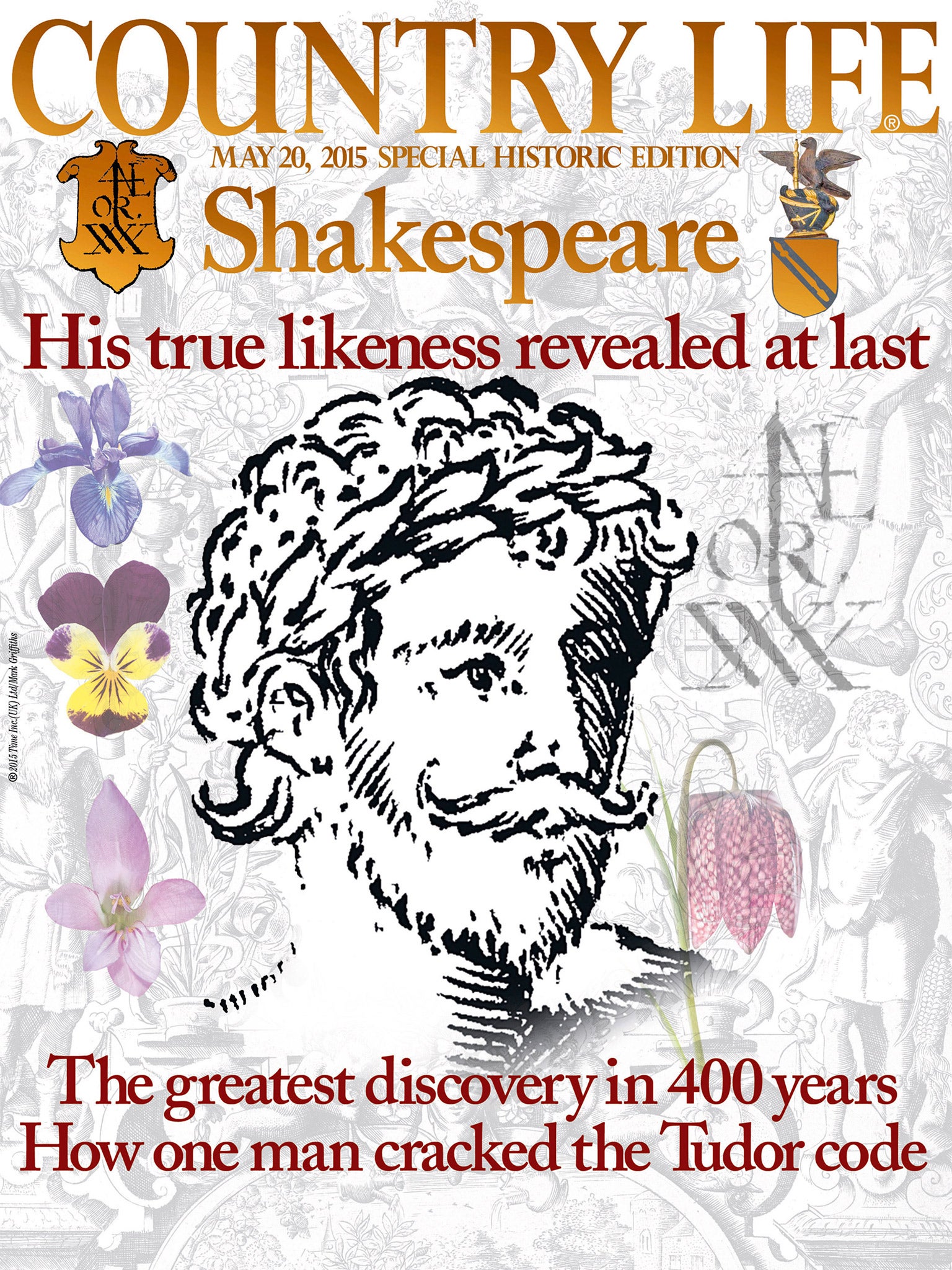

Tudor mystery: ‘Herball’ portrait decoded

The engraving at the front of John Gerard’s Herball or Generall Historie of Plantes has three figures, but the interest lies with the last, which botanist and historian Mark Griffiths called the “Fourth Man”. Mr Griffiths identified the 16th century book’s author John Gerard, Flemish botanist Rembert Dodoens, and Lord Burghley as the first three figures depicted by interpreting the symbolic allusions in the image. A similar strategy of decoding the varied symbols point towards the “Fourth Man” being a 33-year-old William Shakespeare, he said. First of all is a laurel wreath marking the figure out as a writer – being an allusion to Apollo, god of poetry.

In one of the figure’s hands is a Snakes Head Fritillary, a rare flower from the lily family, which is referenced in Shakespeare’s earliest poem in print: “Venus and Adonis”, published in 1593. The flower is unusual in re-tellings of the myth from the time as Adonis usually changed into an anemone. An ear of sweetcorn in the bearded man’s other hand refers to his earliest published play, “Titus Andronicus” from 1594, as it is referenced in a speech given by Marcus Andronicus.

The irises next to him are referenced in “Henry VI part I”. The plinth on which the figure stands has a “W” for William and “OR” engraved. Mr Griffiths believes the latter refers to Shakespeare’s family crest after his father got a gold coat of arms (OR is the heraldic term for gold).

The theory becomes more complicated with the other markings on the plinth: the “Sign of Four” – similar to a coat of arms used by trades including printers and stationers – with an “e” next to it.

Mr Griffiths says the Elizabethans used the Latin term for four – “quater” – and adding the “e” creates the word “quatere” which translates as “to shake”. A rebus showing a spear is also on the plinth, and combining the words creates “shake-spear,” Mr Griffiths said. “I realised there was a method to these figures. Their identities were encoded in the plants around them,” he added.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments