William Shakespeare's birthday: How the Bard bade farewell through Prospero and The Tempest

'We are such stuff as dreams are made on, and our little life Is rounded with a sleep'

William Shakespeare (1564-1616), perhaps the finest mind to ever put quill to parchment, is famously thought to have been born and died on the same date - 23 April.

This Monday therefore simultaneously marks the 454th birthday of the Bard of Avon and the 402nd anniversary of his death.

Shakespeare was 52 when he was laid to rest at the Church of the Holy Trinity in his hometown of Stratford-upon-Avon, Warwickshire, leaving behind 154 sonnets and the 39 tragedies, histories and comedies that continue to dominate the world's theatrical stages to this day.

The Elizabethan playwright casts an almost immeasurably vast shadow over British culture. He has shaped the English language and our everyday speech to a far greater extent than we commonly consider.

When we commend someone for having "a heart of gold", we are quoting Henry V. When we dismiss something as "neither here nor there", we echo Othello.

Common phrases like "wild goose chase", "dead as a doornail" and "with bated breath" all derive from his plays, the Bard's use of metaphor inexhaustibly inventive.

Shakespeare's knack for saying a great deal in a few words was likewise an extraordinary gift.

The melancholy Jaques' discourse on the "seven ages of man" from Act II, Scene VII of As You Like It (1599) maps out the human condition from infancy to old age, cradle to grave, in one relatively short speech:

"All the world's a stage,

And all the men and women merely players;

They have their exits and their entrances,

And one man in his time plays many parts..."

Hamlet's famous soliloquy pondering suicide or Macbeth's haunted reaction to news of his wife's demise are equally pithy: "Life's but a walking shadow, a poor player that struts and frets his hour upon the stage and then is heard no more."

This uncanny skill is brilliantly demonstrated in The Tempest (1611), his final play, in which the character of Prospero, a sorcerer stranded in exile on an "enchanted isle" with his daughter Miranda, is often taken to represent the playwright himself bidding farewell to his public and meditating on his own mortality.

"Our revels now are ended. These our actors,

As I foretold you, were all spirits and

Are melted into air, into thin air;

And - like the baseless fabric of this vision -

The cloud-capped towers, the gorgeous palaces,

The solemn temples, the great globe itself,

Yea, all which it inherit, shall dissolve,

And like this insubstantial pageant faded,

Leave not a rack behind. We are such stuff

As dreams are made on, and our little life

Is rounded with a sleep..."

That phrase "such stuff as dreams are made on" gave cinema one of its most famous closing lines when Humphrey Bogart's Sam Spade applied it to the titular artefact in The Maltese Falcon (1941), the coveted bird statue standing for the hopeless dreams and grasping ambitions of men in defiance of our own impermanence.

At The Tempest's close, Prospero renounces magic, pledging to break his staff and "drown" his books. He frees his servant sprite Ariel, makes peace with the monstrous Caliban ("this thing of darkness I acknowledge mine") and forgives his usurping brother Antonio, the Duke of Milan, who conspired to banish him.

The mage has engineered Miranda's engagement to Ferdinand, Prince of Naples, and thus secured her happiness and is now turning his attention towards his own fate.

The above passage - from Act IV, Scene I - contains an explicit reference to "actors" and another to "the great globe", often read as a punning allusion to the Globe Theatre in Southwark where many of his plays were performed.

In his final soliloquy, the play's epilogue, Prospero considers the diminishing of his powers and the ravages of encroaching age:

"Now my charms are all o'erthrown,

And what strength I have's mine own,

Which is most faint."

Finally, he asks the audience for their applause, drawing the performance to a close and freeing him from his "project... Which was to please":

"But release me from my bands

With the help of your good hands...

As you from crimes would pardon'd be,

Let your indulgence set me free."

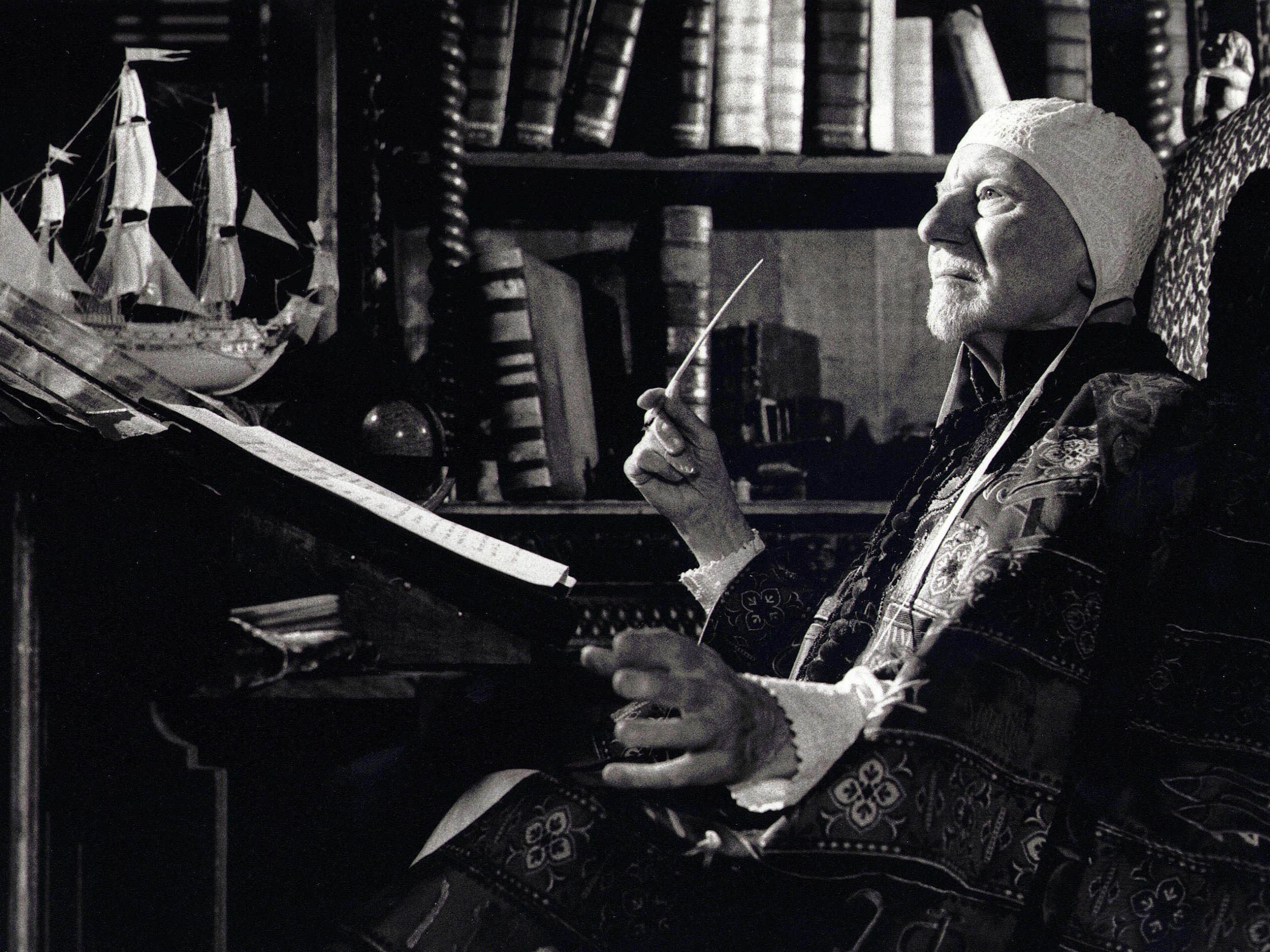

Doubts have been expressed in academic circles over whether Shakespeare really intended Prospero as a self-portrait, with some suggesting he might instead have based the character on John Dee (1527-1608), the Tudor polymath, astrologer and alchemist who attempted to communicate with the spirit realm.

But the parallel was good enough for Samuel Taylor Coleridge and the temptation to interpret The Tempest as an adieu is hard to resist, the broken staff a perfect metaphor for the writer laying aside his pen.

"Our revels now have ended."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks