Trevor Nunn: How the genius Terence Rattigan made a comeback years after his unjust rejection

Nunn, who returned to Rattigan following the huge success of ‘Flare Path’, talks about his love of the British dramatist, as his new production of ‘Love In Idleness’ transfers to the West End

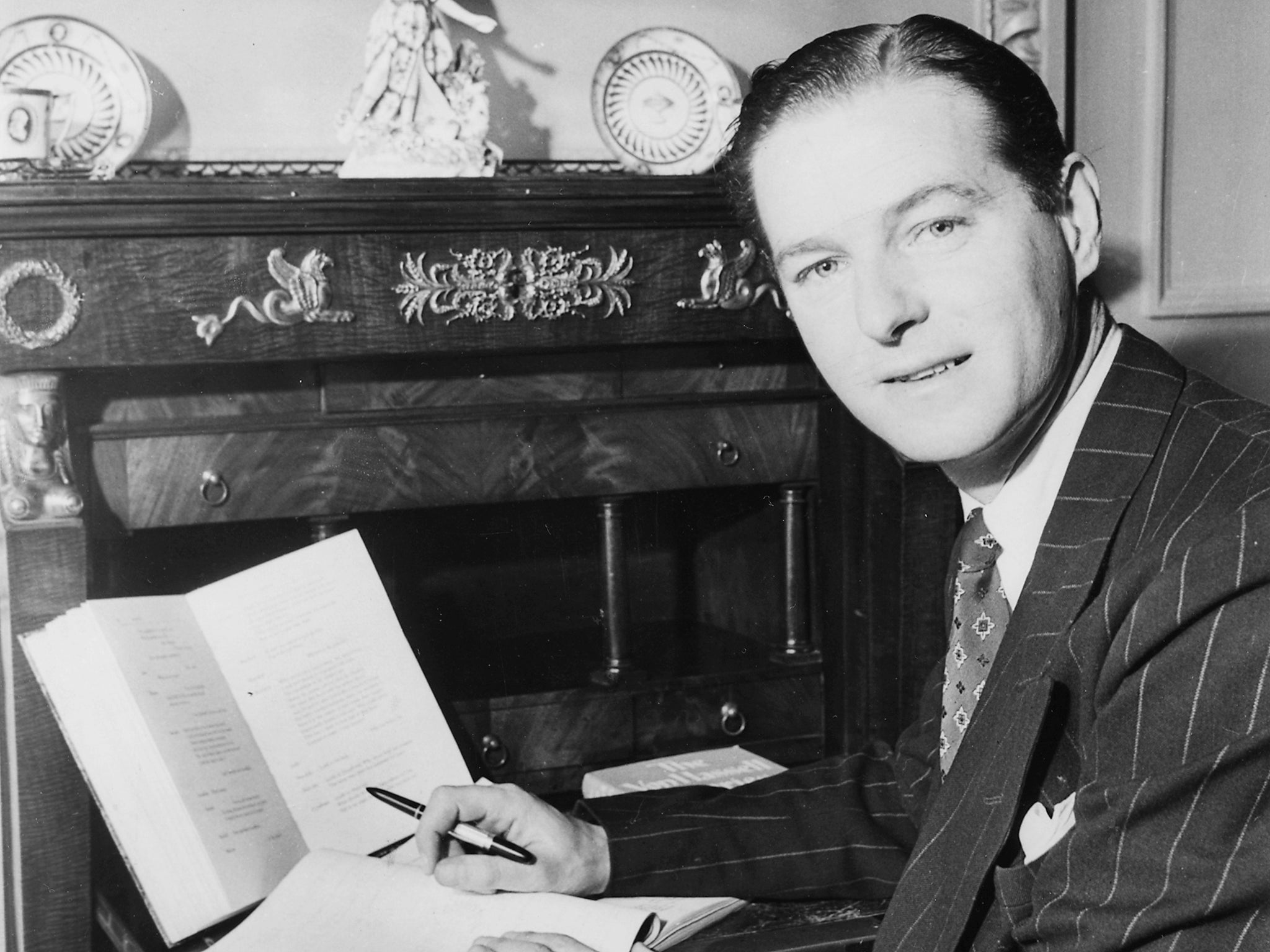

Terence Rattigan is a dramatist of genius. There, I have said it straight out – no ifs or buts, no shilly-shallying. I am, of course, expressing my opinion, but I venture to suggest that we of that opinion are now becoming increasingly numerous.

During the middle years of the previous century, the attribution of genius to works of Terence Rattigan would have attracted pretty universal agreement. Along with Noël Coward, he was the most famous and successful, daring and original English playwright of the age.

Having become known as a confectionist of romantic comedy, Rattigan went on to write about fear, despair, loneliness, illicit relationships, suicides and social politics. He never lost his ability to create comic situations and expertly crafted comic language, but his priority was increasingly the creation of character, complex, contradictory and cogent. There is, in my estimation, one other C-word to describe his achievement: Chekhovian.

To have been, as he was, educated at Harrow, suggests a privileged background, but he was there in fact as a scholarship boy. He held left-wing views and at one early stage of his career tinkered with the possibility of joining the Communist Party.

He bravely joined the RAF early in the Second World War and served as a gunner in Bomber Command. Like many of his theatre colleagues at the time, he knew he would sacrifice his writing career if he declared his homosexuality, and thus, more than once, he was persuaded into adapting a relationship that he had written originally for two men into an “acceptable” heterosexual story.

This, then, is the dramatist who, at the pinnacle of his fame, was suddenly discarded as passé, middlebrow and no longer relevant. What happened to Rattigan was more abrupt and, in many ways, cruel than being erased by time. He was rejected by certain newspaper critics, who had rightly hailed the arrival of Look Back In Anger but who, in the process, declared that any play from then on not written by or about an Angry Young Man was worthless.

Chief among these was the always flamboyant and frequently shocking Kenneth Tynan, who announced that Look Back in Anger by John Osborne was the beginning of the future, relegating everything that had gone before to the past.

But the unkindest cut of all was still to come. Tynan was then appointed as the dramaturg of the new National Theatre, advising and influencing Olivier on what should and should not be programmed. Noël Coward was celebrated and brought back within the fold. Inexplicably (especially as Olivier had been such a close friend and colleague), the doors of the new National Theatre at the Old Vic slammed shut on Rattigan. He was out. He died believing that he would not be remembered, nor readmitted to the roll call of our national theatre.

Who laughs last, laughs longest. Fashion operated as ever, the plays of the Angry Young Men were largely consigned to social history, to be followed by the period of plays demanding revolution and then the much admired state of the nation plays, but Rattigan is now being rediscovered as a writer who defies the century’s onrushing escalation of social, political and scientific change, because his human insight was and remains so penetrating.

I first encountered a Rattigan play when, still unversed in the ways of both the world and the theatre, I directed a professional revival of The Deep Blue Sea. My youthful response to this shocking and shattering play was that it derived directly from Ibsen – that is, a personal story with huge social implications. I thought of it as a masterpiece, yet I failed to turn that admiration into a decision to read everything Rattigan had ever written.

When I came to inherit the directorship of the RSC from my mentor, Peter Hall, I became obsessed with the rediscovery and the vindication of neglected and lost works. We found Boucicault’s London Assurance, unperformed since its original production and O’Keefe’s Wild Oats, untouched since 1699; we excavated a series of plays by Gorky, every one of them as original as they were epic; we gave life to neglected Shaw plays; we retrieved Harley Granville Barker from outer darkness – but we didn’t rescue Rattigan. I admit it, but I can’t explain or defend it.

As the rediscovery of Rattigan began in earnest a decade ago, I was lucky to be asked by producer, Matt Byam Shaw, to look at Rattigan’s war play, Flare Path, untouched by the London theatre since the year of its original production. Again, I thought “this is a masterpiece”.

More recent productions have underlined and increased the sense of Rattigan’s sublimity – After the Dance and The Deep Blue Sea at the NT, Cause Celebre and The Winslow Boy at the Old Vic, Variation on a Theme at the Finborough – each play seeming to say something enduring and relevant to our 21st century selves.

A few months back, in discussions with the Menier Chocolate Factory, I was lucky enough to stumble upon a little-known Rattigan called Love in Idleness, a play which had not been performed on the London stage since 1944. I was magnetised by its subject, and yet... and yet... something about the play seemed to be soft-edged.

The volume I was reading contained another Rattigan I had never heard of, called Less Than Kind. My incomprehension doubled as I realised the names of the characters in these two plays were pretty much identical. It transpired that Less Than Kind was a finished Rattigan work that had failed to find favour and thus had been unperformed. But this play was picked up by the world famous acting duo of Alfred Lunt and Lyn Fontanne, who were interested in the concept, but who required it to be less political and more audience-friendly. So Less Than Kind was rewritten and became Love in Idleness.

At the time, Rattigan expressed immense gratitude to the Lunts for helping him to revive and give successful West End and Broadway life to his earlier failed effort. But decades later, he confessed that he wished he had been stubborn and brave enough to stick to his guns. His rewrite, he feared, had sacrificed political edge, seriousness and emotional complexity.

All this I discovered by reading an introduction to these two plays by Dan Rebellato. Fatefully, the editor had written that perhaps “an enterprising director will come along and make a synthesis of the two versions”. Feeling immensely enterprising at the time, I locked myself away and a made a “conflation”, thankfully accepted by the Rattigan estate and the Chocolate Factory.

As we moved forward with the reworked ‘version’ of both plays – every word written by Rattigan – we realised that in effect, we were embarking on a world premiere.

The fact that the show is now moving to the Apollo Theatre in the West End is a matter of great joy for all involved – but the joy we collectively feel is for Terence Rattigan.

In London, at present, we have so many theatres named after the titans of a previous age – the Coward, the Novello, the Gielgud, and more recently, the Pinter. Is it not time for London theatre to celebrate an enduring genius by naming a West End theatre The Rattigan?

Trevor Nunn directs ‘Love in Idleness’, which runs until 1 July at London's Apollo Theatre (www.nimaxtheatres.com)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks