The dancers voting with their feet

The rise to power and brutal rule of Robert Mugabe is the subject of a daring ballet choreographed by a Zimbabwean exile – but can dance ever express such horrors? Alice Jones reports

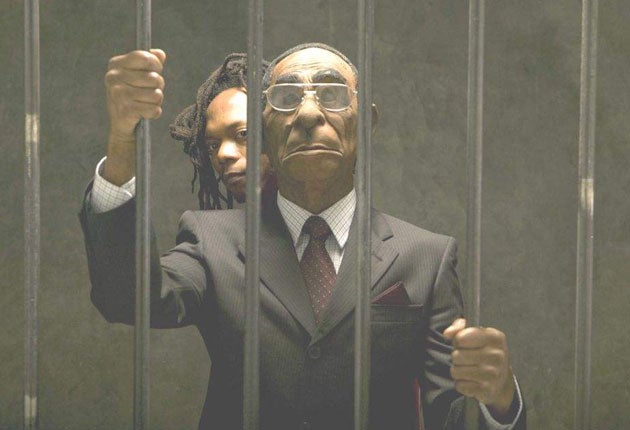

A man pushes a wheelbarrow full of bricks on to a bare stage bordered by corrugated iron shacks. Opposite him stands a dancer wearing a pinstripe suit, checked shirt and maroon tie. The ensemble is topped off by a rubber mask. The belligerent, bespectacled face is unmistakeable – it's Robert Mugabe.

The first man is joined by others who, slowly and deliberately, begin to hurl the bricks at Mugabe. In a stylised sequence of steps set to soothing, swooping classical strings, the President is brutally stoned by his own people. He sinks to the ground, tries to get up and cries for help but his desperate pleas fall on deaf ears. The curtain falls.

So runs the final scene of My Friend Robert, a new ballet about the rise of the Zimbabwean President, Robert Mugabe and the gradual disintegration of the country under his controversial leadership sandwiched into the Heart of Darkness performance. Choreographed by Bawren Tavaziva, who left his native Zimbabwe 10 years ago for a new life in London, the work tackles the last 30 years of his country's troubled history.

From the heady early days of independence in 1980 when the election of Mugabe as the country's first black leader empowered ordinary Zimbabweans, it moves, via last year's violently chaotic elections, to the present day and a nation ravaged by a spiralling economy, food and oil shortages, drought and twin epidemics of Aids and cholera. That the government has so far refused to acknowledge these crises makes Tavaziva's work daringly outspoken. Its ending, envisaging a violent end to the Mugabe regime, pushes it into the territory of the dangerously dissident. "I usually go home every year. Now that I've choreographed this work, I can't go home", says Tavaziva, who grew up in a township outside Harare. "It will be just too dangerous. I'm not going to risk my life."

Tavaziva created the piece during the Zimbabwean elections last year. "You know when you get to the point when you think things aren't going to get any worse and then they get worse. I didn't think it would get this bad. Everything's out of control."

Driven by anger and frustration, it took him just four weeks to complete. Mugabe is played by Everton Wood, a 39-year-old dancer from Wolverhampton who worked at the Royal Opera House before joining Tavaziva Dance's five-strong company last year. Wearing a Spitting Image-style mask, Wood marches on to the stage at the start of the ballet and strikes a variety of bombastic poses. While the rest of the piece combines contemporary African dance with classical ballet, Mugabe, appropriately, remains a rigid figure. More power than pirouettes, his dance style might best be described as militaristic.

Clips from Mugabe's rousing speeches (including the "So, Blair, keep your England and I'll keep my Zimbabwe," riposte to the Prime Minister's declaration that Africa was a "scar on the conscience of the world" at the 2002 Johannesburg earth summit) and Tavaziva's interviews with exiled Zimbabwean journalists are mixed with the national anthem to create an evocative soundtrack. The choreographer, who honed his musical talents as a child on a guitar fashioned by his brother from a 5-litre tin can and some fishing wire, has added his own choral and percussion-based compositions and the dancers hammer and beat out rhythms on the corrugated iron set.

Can dance do justice to such a political hot potato? "Yes. With my background, stories are told through dance. It's obvious why this government failed – it stayed in power for too long and Mugabe started to abuse his power. Now everybody needs a change, everybody is desperate to get rid of Mugabe and is waiting for him to die. But I also hope this will change people's opinions of Zimbabwe."

It is not, on stage at least, all doom and gloom; Tavaziva's work also has moments of jubilation, celebrating the rise of black power in Zimbabwe. He hopes that his own story, of a "normal black Zimbabwean" who came to the UK and now runs his own company, might act as an inspiration.

"Under white rule... I would not have had the opportunity to get an education or come to England. So there's a positive message, too."

The overriding emotion behind My Friend Robert remains, though, angry protest, particularly in the wake of the country's latest humanitarian crisis which has seen the death toll from cholera rise to nearly 2,000. "I'm angry because it's a country that used to feed everybody else and now we are really suffering," says Tavaziva. "You see it on television and it's an embarrassment. The government is still claiming there's no cholera. It's the same thing they did with Aids and now they can't control it." Most of Tavaziva's family remains in Harare, including his octogenarian parents, brothers and "about 20" nephews and nieces. There have been, he says, "lots of incidents" involving his brother, a campaigner against the Mugabe regime. "He's always in trouble, always running away..." Other friends and family were beaten up by government troops in the run-up to the elections, some of them blinded, their eyes gouged out with screwdrivers. "It's brutal," he says. "If I had the opportunity to get my parents out of the country for a while, that would be fantastic, but everyone's seeking asylum."

Tavaziva's own route out of the ghetto came when the National Ballet of Zimbabwe paid a visit to his local community hall, offering contemporary dance classes to under-privileged children. Tavaziva leapt at the chance. As a child, he had dreamed of dancing, forming a group, New Limits, with his two brothers, performing routines and lip-synching American pop songs on the streets. He soon gained a place with the City Youth Dance Group. From there he joined Tumbuka, a company set up by Neville Campbell who had left his job as artistic director of the British company, Phoenix Dance to set up a new troupe in Zimbabwe. Tavaziva stayed with Tumbuka for four years until moving to the UK in 1998 to work with Phoenix, Ballet Black and Union, among others. In 2004, he was a finalist for the prestigious Place Prize and as a result received Arts Council funding to establish his own company.

In the decade since Tavaziva left the country, the opportunities for contemporary dance in Zimbabwe have dwindled. Tumbuka survives only thanks to international funding and all the other companies have either closed down, operate part-time or offer only traditional African dance. "There used to be a national dance company in Zimbabwe but the government pulled the funding. They only fund football. They don't fund the arts." This is perhaps unsurprising in a country in the grip of hyper-inflation, where a newly-launched Z$50-bn note is worth just 84p, but it makes Tavaziva's mission all the more important. "There is no chance I could do what I do here in Zimbabwe. Most of the artists back home don't say what they want and they can't produce work like this. They would just get killed. Being here in England it's really an opportunity to share where I come from and what it's like."

While Tavaziva took his company on tour to Zimbabwe two years ago, a trip home remains out of the question for the moment. "They would attack me. If this piece gets too big and it starts to make an impact, it will start affecting my relatives. I am really worried about it but I felt that it was something that had to be done."

'Heart of Darkness' opens at the Paul Robeson Theatre, Hounslow on 29 January and tours to 1 April www.tavazivadance.com

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks