Richard III: Celebrating the most deliciously wicked study of political ambition and intrigue

In the right hands, this 'tragedy' boasts almost as many laugh-lines as a play by Oscar Wilde

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Soon after Kevin Spacey played Richard III at the Old Vic in 2011, he began to work on the US remake of House of Cards. Over four series now, the Washington-set TV series has given him the scope to mould the charming, calculating, savagely ambitious senator-turned-president Frank Underwood not only into a Shakespearean villain but – in his wise-cracking, bone-crunching fashion – a Shakespearean tragic hero too.

If the partnership in power-lust with his wife (played by Robin Wright) has more than a touch of the Macbeths, Spacey’s ghoulishly witty relish for confidences and conspiracies has another source. In 1996, Al Pacino directed a film about his quest for Shakespeare’s most charismatic tyrant, called Looking for Richard. Just now, Pacino would find him streamed – to critical plaudits and commercial success – on Netflix.

Richard of Gloucester endures because power and politics – in parliaments, in boardrooms, in offices, in colleges – has not in its human essence changed since Richard Burbage brought the “bottled spider” to the stage in 1593. Smart, pitiless, cynical and (finally) self-hating opportunists driven by some real or imaginary grievance still clamber up the tottering greasy pole. In the play, Lord Hastings likens the perch of power to “a drunken sailor on a mast,/ Ready, with every nod, to tumble down”.

Actors and directors can choose either to magnify or minimise Richard’s hump. Does the “deformity” lie chiefly in the body, or the mind? Antony Sher made the “spider” a sinister reality. Ian McKellen’s stiff-limbed but strapping fascist despot focused on the mental scars. However you interpret the injury that drives him, at the top of that mast Richard finds not contentment but panic, paranoia and – most of all – soul-eroding solitude. “There is no creature loves me,” he laments on the eve of Bosworth, “And if I die, no soul shall pity me.”

Critics and play-goers sometimes find Richard’s brief reign – after he has plotted, betrayed, lied, seduced and slaughtered his way to the throne – something of an anticlimax. True, Shakespeare can no longer treat Richard (and us) to breath-stopping displays of mafioso charm such as the scene in which he sweet-talks the newly widowed Lady Anne into his clutches, and his bed: “Was ever woman in this humour woo’d?/ Was ever woman in this humour won?” His gags are killing jokes. What the finale delivers is the fearful emptiness of power, as the ghosts of his victims return to haunt the usurping king and goad him to destruction. “Despair and die,” they all ritually intone.

Often hurled by royal women, figures both commanding and constrained, curses punctuate this play. None freezes the blood more than the icy vat of poison flung by Richard’s nightmare mother, the Duchess of York, at her scapegoat son: “Thou camest on earth to make the earth my hell./ A grievous burthen was thy birth to me;/ Tetchy and wayward was thy infancy…”

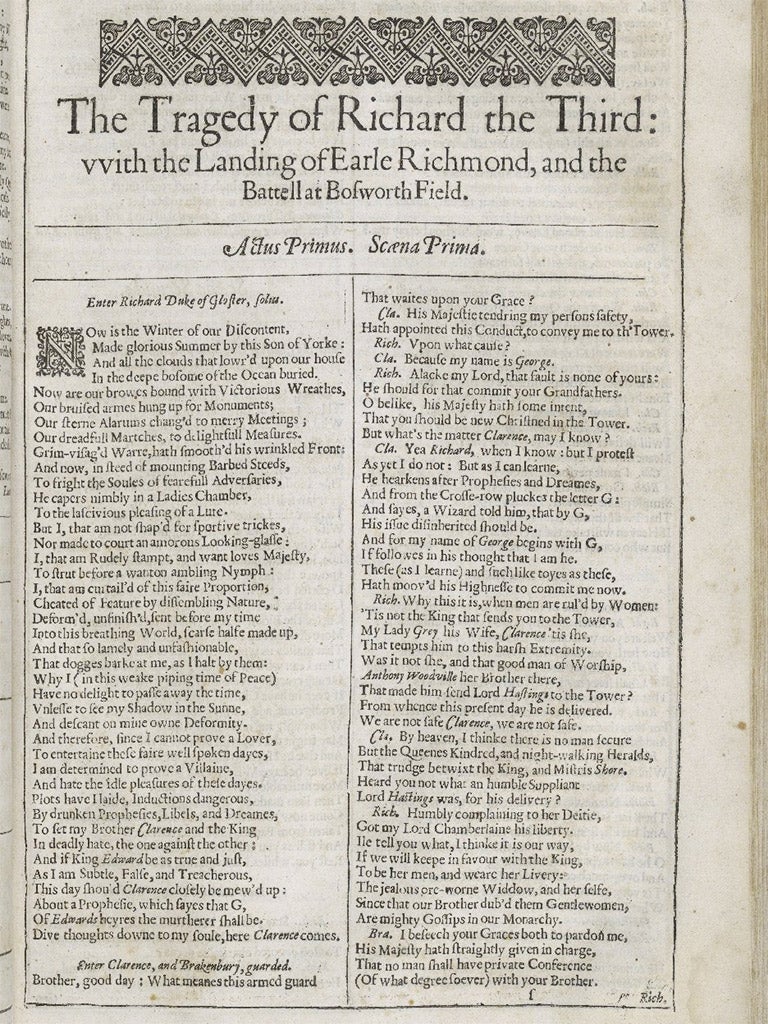

These moments sharpen an ongoing quarrel over the nature and origin of evil. Has Richard entirely chosen his blood-stained trajectory, or can we trace it back deep into a damaged past? When, in the opening soliloquy, he announces that “I am determined to prove a villain”, the first verb captures the ambiguity. From the domestic abuser through the mayhem-spreading terrorist to the genocidal dictator, the same puzzle presents itself in every day’s headlines. The First Quarto edition calls this work not a history but The Tragedy of King Richard III. Ultimately, it feels like one. Yet in the right hands, this “tragedy” boasts almost as many laugh-lines as a play by Oscar Wilde.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments