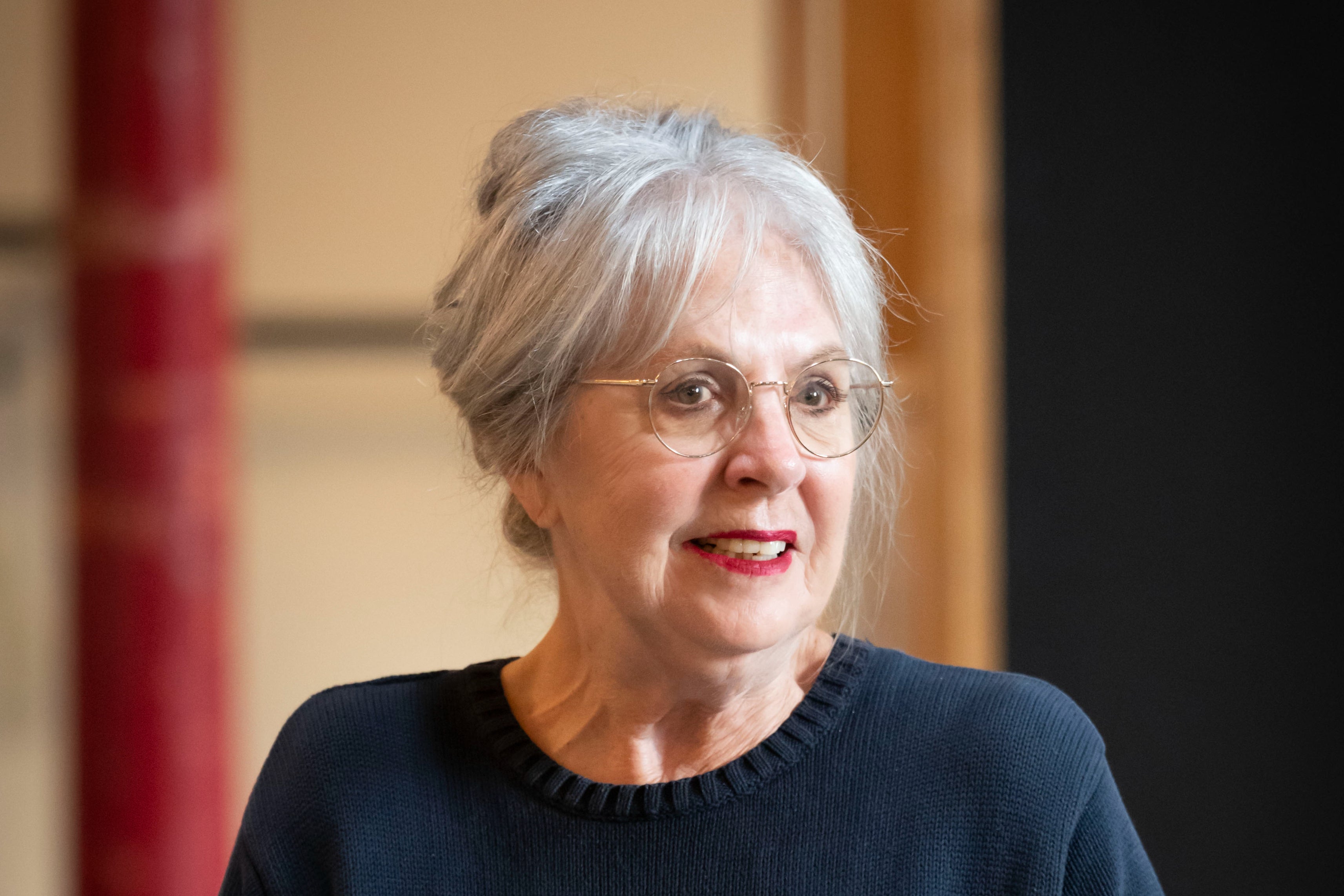

Penelope Wilton: ‘The royals are there because we want them – not the other way round’

She doesn’t like standing ovations and thinks taking up the role of Queen Mother in her late Seventies is less work compared to being a working royal – but Penelope Wilton has never been one for an easy life. Here, she talks to Sarah Crompton about her marriage to fellow actor Daniel Massey, ‘Downton Abbey’ and what it was really like working with her best friend, Michael Gambon

Penelope Wilton is considering the behaviour of theatre audiences, as she prepares to embark on a stint in the West End. “It must be awful when people start being drunk and everything. I can’t think of anything worse,” she tells me, raising both eyebrows.

She isn’t fond of the growing craze for standing ovations either. “Everyone getting up at the end seems an odd thing to do, too. I am quite happy sitting there myself. I don’t expect people to get up, but everyone seems to now. It’s another phase everyone is going through.”

She laughs. It’s quite likely that Wilton, returning to the stage at the age of 77, will herself be the subject of a standing ovation at the end of her performance as Queen Elizabeth, the Queen Mother in Backstairs Billy, a new play by Marcelo Dos Santos. But it’s equally typical that she doesn’t anticipate one.

During a career that took her from playing Cordelia opposite Michael Hordern’s King Lear in 1969, through leading roles in many of Harold Pinter’s later plays, to television fame in the sitcom Ever Decreasing Circles, the period drama Downton Abbey and Netflix’s dark comedy After Life, Wilton’s remarkable talent has somehow never achieved the mega-stardom of, say, Judi Dench. There’s a quiet modesty about her performances that makes it easy to overlook her brilliance.

We’re talking in one of the warren of rooms at the Union Chapel in North London where she is rehearsing. Despite a long day, she looks impeccable and unruffled, in a blue jumper and elegant necklace. She doesn’t, it has to be said, look much like the Queen Mother. “I’ve had to change my shape with my costume,” she says, with that familiar quick smile. “She was much smaller than I am and had a much fuller figure. But I have this most wonderful designer Tom Rand who knows exactly what she would have worn and the kind of materials.”

In any case, she adds: “I’m not an impersonator. You have to play with what you have, which is a script.”

She loved the play the moment director Michael Grandage sent it to her. Set in 1979, it focuses on the relationship between the Queen Mother and her servant William “Billy” Tallon, played by Luke Evans. Tallon became a member of the royal household in 1951 when he was 15, joined the Queen Mother’s staff at Clarence House in 1960, and stayed loyal to her until she died in 2002 at the age of 101. “It’s about their friendship,” explains Wilton. “They never crossed the line, there was a hierarchy. But he made her life much more entertaining.”

She has had the occasional encounter with royalty herself. The late Queen Elizabeth II presented her with an OBE in 2004 and she was made a Dame in 2016 by Prince William. “A lovely, tall young man,” says Wilton, with another quick smile. She’s also been to both Buckingham Palace and Clarence House, to perform in charity events. “They are very welcoming. There is nothing austere about the palace. It’s a very large house but you feel you are coming into somebody’s home.

“They [the royal family] are there for us, you do feel that. They are there because we want them to be there, it’s not the other way around. I am a believer in a head of state that hasn’t been voted in. It’s non-political and it’s wonderful for bringing people to the country with all the pageantry. They do extremely good work. I would hate to have the job. I couldn’t bear it, talking to all the people they have to talk to, being interested all the time and all the hard work that goes into that.”

For all her friendliness, there’s a polite reserve that wraps itself around her as Wilton talks. You sense she doesn’t much like talking about herself, yet she has had an exceptional career, one that required more steel than she perhaps reveals.

I am a believer in a head of state that hasn’t been voted in. It’s non-political and it’s wonderful for bringing people to the country with all the pageantry

Born in Scarborough, her family had theatrical links. One great-grandfather owned a cinema in Newcastle, and her uncle was Bill Travers (of Born Free fame). More significantly for Wilton, her aunt was Linden Travers, star of films such as No Orchids for Miss Blandish, while her mother began a career as an actress and a dancer before leaving the stage to bring up Penelope and her two sisters, one older and one younger.

Her mother was delicate – she died of cancer when she was 60 – and so the girls were sent to “a terrible boarding school”. “I think if we had been boys, we would probably have had a better education, but for that generation, women’s education wasn’t that important. We were sent to these second-rate places and one got absolutely nothing out of it. I’ve always been rather cross about it but there’s nothing you can do about it.” She laughs again, almost apologetically. “We all educated ourselves really.”

Acting seemed an obvious choice of career. “I was a bit dyslexic, so I liked to hear language. I wasn’t good at anything else.” But after training at the Drama Centre in London, she worked in a shop for 18 months, before landing a job at the Nottingham Playhouse. It was there, in 1969, that she was Cordelia opposite Hordern’s Lear, before arriving in London to work at the Royal Court, where she played opposite another eccentric theatrical giant, Ralph Richardson, in John Osborne’s West of Suez.

At curtain calls, Richardson used to ask her whether she had anyone watching her that night and tell her he had a friend called Mr Gordon who used regularly to visit his dressing room. “It was only on the last night that his dresser came all the way upstairs to my dressing room carrying a large gin on a silver tray for me, that I realised he was just teasing me,” she says, with a grin. “He had a large gin at the end of the show! He was a very nice man and I was very young.”

Her great breakthrough came in 1978 when she was cast in Harold Pinter’s Betrayal, as a woman loved by her husband (played by Daniel Massey, her real-life husband at the time) and his best friend (Michael Gambon). It’s a legendary production – and one that altered Wilton’s life, leading to a long working relationship with Pinter. “He was a wonderful man. People like him, [Czech filmmaker] Karel Reisz, Alan Ayckbourn – they were a great influence on me. Their taste, their courage about what they did, the taking risks and the talent. Harold was a big figure in my life for a long time.”

Yet she nearly turned the part down. After suffering a stillbirth of a son, Wilton had three months previously given birth to a severely premature daughter, Alice. “I was in the hospital from 12 weeks until I had her at 30 weeks. She was 2lbs and 9oz. But she’s never looked back.” Wilton’s smile widens as she remembers how her daughter thrived. “She’s sick of that story. She always says, ‘Mum, don’t tell it’.”

It was her older sister Rosemary who persuaded her that if she refused the opportunity to play Emma because she was worried about her baby, then she would regret it her whole life. “I thought about that because she always gave me very good advice,” she says. “I don’t know what would have happened if I had turned it down, but it would have been a silly thing to do. So I just had to manage it.”

Not that it was easy. The first night was a crisis because the stagehands were threatening to strike, but Wilton was coping with her own emergency. “My nanny had left, and I was dashing around trying to find somebody to look after the baby while I went on and did the show. It was unbelievable. I found someone who had been in hospital and who also had a premature baby, and she took her in until I got home.”

Michael Gambon was very quick, very deft, and he had the best timing. You can’t learn any of those things – you either have them or you don’t

She loved working with her husband Massey who stayed part of her life even after their divorce, eventually marrying Wilton’s younger sister, Linda. “He was very loved by the family, but he was a depressive and he had a very difficult childhood. Both he and [his sister] Anna. They seemingly had all the money in the world, but they had absolutely no mothering or fathering, so both of them were very anxious.” Linda also had two children from a previous relationship, and they were close to Alice. “They were all together and my father was very fond of Dan. I don’t want to go into it, but it was all fine.”

She also maintained her bond with Gambon, with whom she also worked in Alan Ayckbourn’s The Norman Conquests and Sisterly Feelings, in Shakespeare’s Much Ado about Nothing, and then later on television in the Elizabeth Gaskell adaptation Wives and Daughters. His recent death led to a general outpouring of affection.

“He was a friend,” Wilton says, simply. “He was very quick, very deft, and he had the best timing. You can’t learn any of those things – you either have them or you don’t. He was also very romantic. He didn’t look like a romantic person but when he played Jerry in Betrayal it was heartfelt and surprising from him. As a person, he was incorrigible. He was the best company, witty, and he did terrible things.”

A famous practical joker, Gambon took advantage of the fact that the course of the action in Sisterly Feelings was determined by the toss of a coin. He made a coin with two heads, so that every night Wilton would have to change in an onstage tent, which meant the men in the company could go off for the interval and have a drink because they didn’t have a costume change. Finally, she realised what was going on – and simply called “tails”. “I caught him out there,” she says, with a laugh, mimicking his double take. “He was such good fun.”

The sense of being part of a company, of making work together, is why Wilton loves her work. The same spirit infected the Downton Abbey set, where long days of filming bound the whole cast together. Wilton particularly relished the time her character Isobel Crawley spent with Maggie Smith’s Lady Grantham.

“I was an admirer of hers when I was a young actress and saw most of the things she did at the National Theatre,” she says. “It was just a thrill for me to work with her. It is so good to work with someone who is a great deal better than you are, everything is real. She’s marvellous.” Off-screen, the pleasure continued. “She likes stories and I like stories, so we made each other laugh. We played a lot of Bananagrams. All of us played Bananagrams, it’s a great game to play because you can do it quickly and then go off to do a scene and come back.”

The success of Downton means that she is occasionally noticed in the street. Other people know her from her role in The Best Exotic Marigold Hotel films. But Wilton’s first real fame came when she starred opposite Richard Briers in the 1980s sitcom Ever Decreasing Circles. “I didn’t actually think I was famous because I was too busy doing it, but when it was on, people used to recognise you a bit more.”

Briers, she says, was wonderful. “He absolutely knew how to do it,” she says. “It’s agony doing those things because you go along happily all week and then on Saturday you record it live, in front of three cameras. It’s like a car crash. You can’t go wrong because if the audience see you are worried, then they stop laughing. It’s not one thing or another, it’s not theatre and it’s not television. Dickie hated it, but he did it a lot.”

As for the Queen Mother, she was not politically correct, she was an Edwardian lady so she had views that probably wouldn’t be acceptable nowadays, but that’s how it was

Wilton rates Ricky Gervais’s talents as highly as she does those of her past collaborators. She played Anne, the stranger who befriends Gervais’s grieving widower in After Life, offering gentle comfort in his despair. “There are a lot of men who are very moved by that relationship,” she says, thoughtfully. “We started it before Covid and then Covid came along, and it seemed to relate to what people were dealing with at the time. It was wonderful working with him because the buck stops with him. So it’s very spontaneous.”

In Backstairs Billy, Wilton once again exercises her gift for comedy. The play, she says, is part romp and part critique of the times. “It’s set in 1979, which seems a similar time to the one we are going through now, with a lot of difficulties politically and the country having a nervous breakdown. Mrs Thatcher was about to come in, and there was a lot of unrest.

“As for the Queen Mother, she was not politically correct, she was an Edwardian lady so she had views that probably wouldn’t be acceptable nowadays, but that’s how it was. We have to be true to the time we are working in, otherwise there is no point.”

She doesn’t fear exhaustion in performing night after night. “I find filming much more tiring and much more boring. The theatre, when we get it up and running, is only two hours. It’s hard going,” she tells me, “but having done it all one’s life, that’s what you’re used to.”

‘Backstairs Billy’ plays at the Duke of York Theatre until 27 January 2024

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments