Monroe, Miller, Montand, Signoret: When golden couples meet

Fifty years on, a new play explores what went on during the four months the quartet spent together in 1960.

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Hollywood, the summer of 1960. In a bungalow at the Beverly Hills Hotel are Marilyn Monroe and her husband, the playwright Arthur Miller. Next door, the golden couple of French cinema, Simone Signoret and her husband Yves Montand. Monroe and Montand are starring in the George Cukor movie, Let's Make Love.

Miller and Monroe's unhappy marriage is reaching its endgame. He has rewritten the script for Let's Make Love and, after Gregory Peck, Cary Grant, Charlton Heston, Yul Brynner and Rock Hudson have all turned down the male lead, Miller suggests Montand, who starred in the French movie version of The Crucible.

Montand is a very French version of the matinee idol: a communist and former lover of Edith Piaf (among many others), a music-hall crooner who marries the country's greatest actress and develops a film career of his own. To shoot Let's Make Love, he and his wife, renowned as a left-wing intellectual as well as an Oscar-winning actress (for her 1959 role as an alluring older woman, in Room at the Top) decamp to Los Angeles.

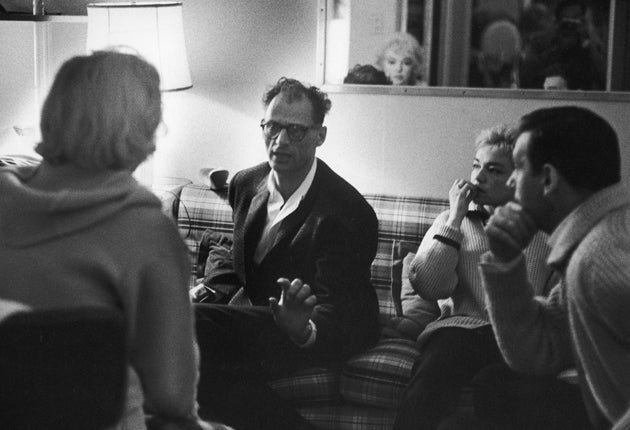

For those four months, their corner of the Beverly Hills is as much of a crucible as Salem in the 1690s. Signoret and Monroe become close friends. They all spend a lot of time together. There are photos of the two couples eating dinner, Montand holding forth while Monroe oozes out of a black dress. Then, once the film has wrapped, Monroe and Montand have a very public affair.

This charged episode has long fascinated Scottish playwright Sue Glover and is the subject of Marilyn, her latest play for Glasgow's Citizens Theatre. "The force of this meeting changed Simone Signoret's life completely," says Glover, best known for her 1991 play Bondagers. "For her, it was never the same again. It was a pivotal moment."

Glover confines the two women into the hairdresser's chair, their roots coated with the aggressive peroxide of the 1960s. With the help of the third cast member, their stylist Patti, the writer combs through the two icons' fraught relationship, while also considering fame, celebrity and the sexual politics of mid-20th century cinema.

"There is the so-called dumb blonde, who isn't dumb at all, and the egghead. And then you find that they've got quite a lot in common."

Signoret, played by Dominique Hollier, was a force in French intellectual life, regularly appearing on political discussion shows and, later in her life, ringing up producers to suggest items they might want to cover. This was her first trip to the US, at a time when McCarthy's anti-communism was a national obsession and no bed was safe until it had been checked for reds underneath. Monroe (Frances Thorburn) would, according to the writer, have struggled to articulate her own political position in a TV debate. But, Glover says, she did it her way, "posing for photographers when Miller was subpoenaed to appear in front of the House Un-American Activities Committee."

"Simone was super-intelligent and sharp but Marilyn sometimes took her by surprise. And although Marilyn's politics were rather vague, instinctively she was on the same side as Simone."

In fact, Signoret and Montand had, in many ways, the life Monroe hoped to have when she married Miller. She had lost her baby while filming Some Like It Hot. Signoret had a daughter from her first marriage. They had a wide circle of friends, respect for their professional achievements and their political activism. Montand found fidelity challenging, but behaved himself while his wife was around, whereas Monroe's husband's idea of a romantic gesture was to write The Misfits, in which she starred as a depressed divorcee. Signoret had an Oscar while Marilyn was appreciated for cleavage and wiggle rather than dramatic monologues.

So what, exactly, did they have in common? "They both depended on the man in their lives, to an extent that seems quite extraordinary to us today." Monroe married three times and allegedly had affairs with John and Bobby Kennedy, among others.

Signoret was different. She famously said of Monroe: "If Marilyn is in love with my husband it proves she has good taste, for I am in love with him too." For Glover, that is key to understanding Signoret. "Simone had to have this man."

Let's Make Love was shot the year Monroe turned 34. Signoret was five years older and, while Patti gives their hairlines their weekly bleach bath, they discuss ageing, how long you can stay young and what, in those pre-Restalyne days, you could do to stretch it out.

According to Glover, "Simone is quite categorical: you don't have to do anything. Look, she says, grey hairs, wrinkles. I don't care – but you know that she does." Approaching 40, she has started playing age-appropriate roles: mothers, countesses, what would now be called cougars. "She didn't like it but she did it wonderfully. She won the Oscar for Room at The Top. Later on, in La Veuve Couderc she is a bitter, lustful widow. In Le Chat she plays the wife of someone 20 years older than she is."

This was not for Monroe, who was determined to preserve her world-class erotic capital. "Of course Marilyn was trying to hold on," says Glover. "What else would she do in Hollywood?"

Fearing that her legendary sex appeal was about to curdle, her marriage to Miller crumbling and her self-esteem in the toilet, Montand never stood a chance. "Marilyn was one of these very damaged people who found reassurance in seduction. Miller was already making her feel inferior and Simone would make anyone feel inferior."

Glover thinks Monroe used sex with intriguing, powerful men to fill these perceived gaps in herself. "She liked special people. Marilyn married Miller partly to gain status and knowledge. She desperately wanted to read Ulysses and play Cordelia. She knew the part by heart."

For Signoret, Montand's public betrayal and the ensuing headlines and hoohah, was an unbearable humiliation and affront to her dignity. "It embittered her, for a while she really lost the place, which is what will happen if you will be utterly devoted to a man like that."

Marilyn's downward spiral gained momentum and she died two years after Let's Make Love. Signoret lived until 1985, continued her distinguished career and was nominated for a César for her role in her last film, L'étoile du Nord in 1982. The summer of 1960 may have been a turning point in Signoret's life but she refused to blame her friend for it. After her death she famously said: "She will never know how much I didn't hate her."

'Marilyn', Citizens Theatre, Glasgow (0141 429 0022) tonight to 12 March; Royal Lyceum, Edinburgh (0131 248 4848) 15 March to 2 April

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments