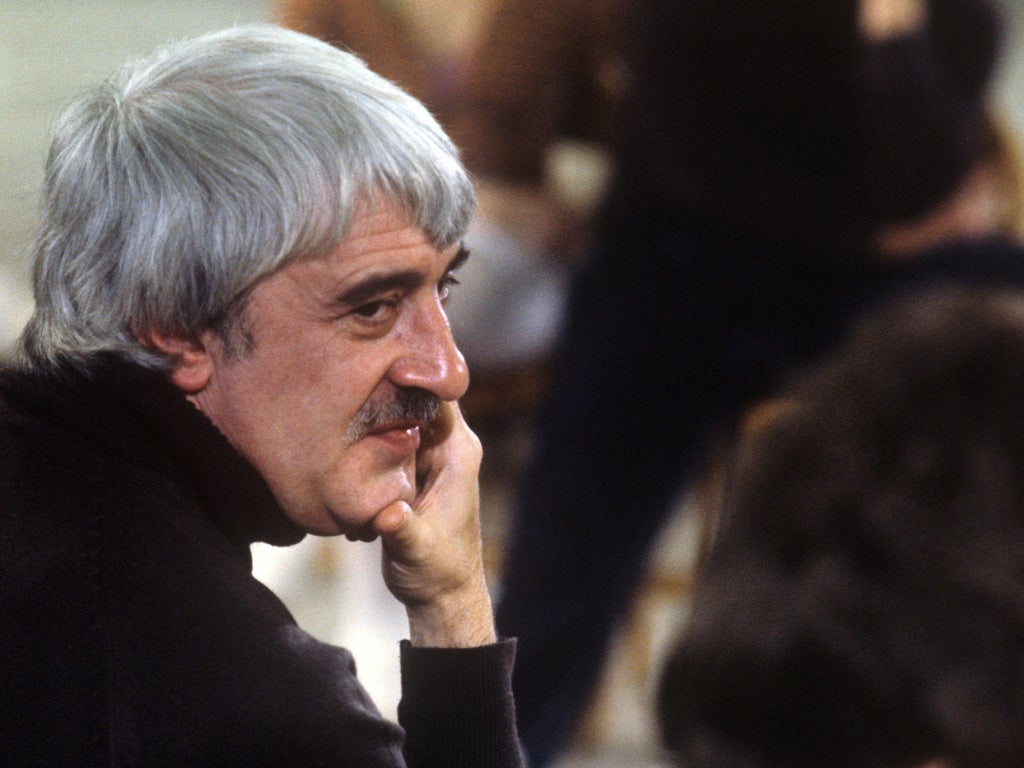

Kenneth MacMillan: Still the Royal Ballet's prince of the pas de deux

Kenneth MacMillan's influence is all around this season

Twenty years ago Sir Kenneth MacMillan suffered a heart attack at the Royal Opera House during a performance of his ballet Mayerling. At the end of the evening, the stunned audience was informed of the great choreographer's death. Two decades on, his star is shining brighter than ever.

English National Ballet is currently on a national tour with his production of The Sleeping Beauty, and the Royal Ballet, with which he spent the lion's share of his career, is about to pay tribute to him in a new triple bill of contrasting works – Concerto, Las Hermanas and Requiem – which opens on Saturday. Involving two abstract works and one very dramatic, this programme displays MacMillan's eclectic scope: he pushed the boundaries of drama in dance further than had ever been seen before in classical ballet.

MacMillan's ballets were of their time, dealing with issues such as repressed sexuality and complex familial relationships that were in vogue during his heyday between the 1960s and 1980s. One might have expected them to seem dated by now.

Not a bit of it. His Romeo and Juliet holds a status second only to Swan Lake. Manon, slated by critics on its unveiling in 1974, has been taken up by some 20 companies worldwide. Initially controversial, too, Mayerling (1978) has become a perennial favourite. Even his version of The Rite of Spring (1962) has not been superseded, despite Aboriginal-themed designs deemed inappropriate by some, and despite reconstructions elsewhere of the original Nijinsky choreography, as well as famous reinterpretations by experimental choreographers such as Maurice Béjart and Pina Bausch. The Judas Tree, his last work for the Royal Ballet, scandalised audiences with its violence – but today, like Mayerling, is sought after by enthusiastic young dancers for the tremendous challenges it poses.

Lady Deborah MacMillan, essentially the custodian of her late husband's ballets, credits their longevity to his insights into human psychology and interaction. "Kenneth revealed himself by what he did on stage more than he ever did in life," she comments. "He was a quiet, even taciturn man, very subtle in his responses. But his understanding of people and how they react to one another still astonishes me. He believed you could do and say anything through dance."

Sometimes he even forgot that the human body has limits: "He once said to Lynn Seymour, 'I want your knees to bend that way.' She had to tell him they just couldn't!"

He often felt crushed by hostile reviews: "Despite this, he kept doing what he felt he had to do. That takes some bravery. He wasn't afraid of tackling whatever felt right to him – whether it was The Judas Tree, which was extremely challenging for everyone, or The Prince of the Pagodas, which threw some people because he went back to a classical language they didn't expect from him."

Just before he died, MacMillan again took his audience by surprise: he choreographed Carousel for Nicholas Hytner's production at the National Theatre. It included a pas de deux showing a boy slowly winning round an antagonistic girl, progressing from combat to passion. Lady MacMillan recalls Hytner telling him: "What you do in a pas de deux is something that takes a novelist or playwright pages to convey."

"It was nice for him to hear that, because he wasn't particularly well by then," she says. "A week later he was no longer with us."

And so, extraordinarily, MacMillan's very last piece of choreography was "June Is Bustin' Out All Over". "It's full of life," says Lady MacMillan. "He went out on a high."

The Royal Ballet's triple bill of Kenneth MacMillan ballets opens on 17 November (020 7240 1200)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks