Is it right for artists to demand their work is destroyed after their death?

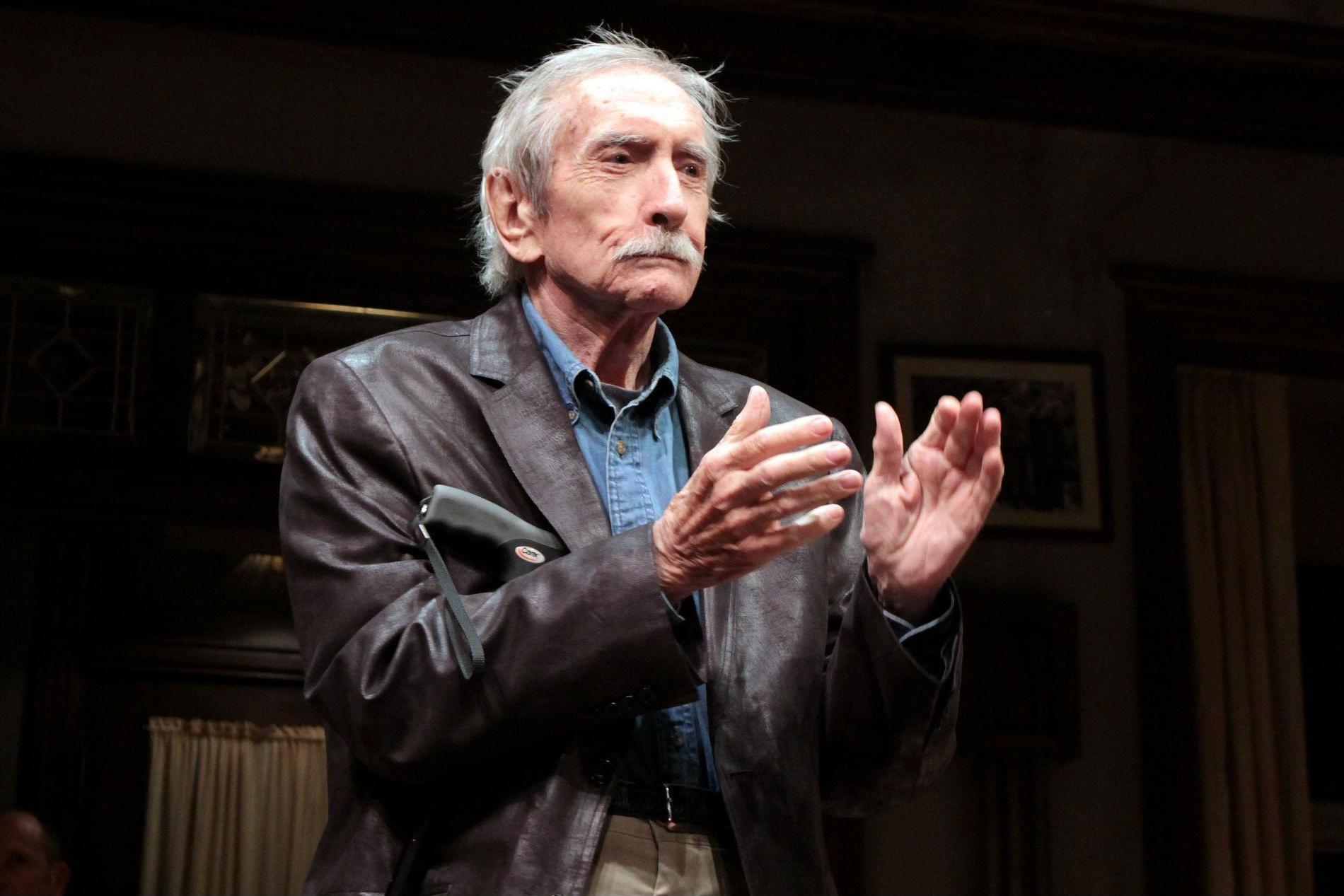

Playwright Edward Albee instructed his friends to destroy any unfinished manuscripts, but could the law step in to save them for posterity?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Edward Albee died last year. But the renowned playwright is making one last request from the great beyond. Albee wants two of his friends to destroy any incomplete manuscripts he left behind.

The instruction – included in a will Albee filed on Long Island, New York, where he lived and died – is unusual but not unprecedented. There is a term in the legal world for such instructions – dead hand control – and, although compliance has varied and enforceability is debatable, they have been attempted by artists from Franz Kafka to Beastie Boy Adam Yauch.

For now, the impact of Albee’s will is a mystery. The executors – an accountant, Arnold Toren, and a designer, William Katz, both longtime friends of the playwright – declined through a spokesman to answer questions. They would not discuss whether any papers had already been destroyed. But the executors have been carrying out other aspects of Albee’s will.

This autumn, at the request of the estate, Sotheby’s will auction off more than 100 artworks collected by Albee; the proceeds, estimated at more than $9m (£7m), will benefit his namesake foundation. (The playwright, who was gay, never married and had no children or close relatives. His foundation, which maintains a residence for artists in Montauk, New York, is the primary beneficiary of his estate.)

The executors have made clear they plan to honour Albee’s desires, even when they might be controversial. In May, for example, they refused to allow a tiny Oregon theatre to cast a black actor as a blond character in a production of Albee’s most famous play, Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, citing the playwright’s intentions as expressed during his lifetime.

Now at stake, at a minimum, are the latest drafts of Albee’s final known project, Laying an Egg, about a middle-aged woman struggling to become pregnant. (One plot element concerned her father’s will.) The play was twice scheduled for production at Signature Theatre, an off-Broadway nonprofit in New York, and twice withdrawn by Albee, who said it wasn’t ready.

Even if the executors destroy Albee’s draft, other copies may exist – a Broadway producer, Elizabeth Ireland McCann, said she had at least a partial version of the script – but it is not clear whether Albee had done work on the project that only he had seen. It is also unclear whether Albee left any other incomplete manuscripts behind or whether the language in the will could be interpreted to apply to early drafts of his published plays.

“Am I disappointed? Yes, because every tiny bit of everything that a writer has written provides insight into that writer’s creative process,” says David A Crespy, president of the Edward Albee Society and a professor of playwriting at the University of Missouri. “But am I surprised? No. He maintained very strict control over the materials that were available to the public.”

Albee is best known for Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, a penetrating 1962 drama that was adapted into a film starring Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton. He won the Pulitzer Prize three times – in 1967 for A Delicate Balance, in 1975 for Seascape and in 1994 for Three Tall Women – and the Tony Award twice, in 1963 for Virginia Woolf and in 2002 for The Goat, or Who Is Sylvia? He also won a Tony Award for lifetime achievement in 2005. His work is frequently staged; a revival of Three Tall Women, starring Glenda Jackson and Laurie Metcalf, is to open on Broadway next year.

The playwright died in September at the age of 88. His will, which he signed in 2012, was filed in Suffolk County Surrogate’s Court; the provision in question says, in part: “If at the time of my death I shall leave any incomplete manuscripts I hereby direct my executors to destroy such manuscripts.”

Until the manuscripts are destroyed, the will says, the executors should “treat the materials herein directed to be destroyed as strictly confidential and to ensure that such materials are not copied, made available for scholarly or critical review or made public in any way”.

Some artists back Albee’s right to decide the posthumous disposition of his writings. “For writers, drafts of unfinished work can be quite sensitive,” says Doug Wright, a Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright (I Am My Own Wife) who is president of the Dramatists Guild of America. “These drafts are not public property; they belong to the author, and the author has the right to determine their fate.”

And James Bundy, dean of the Yale School of Drama, says: “Edward’s choice strikes me as entirely in keeping with his own exacting standards.”

“It’s no more our business than it would have been if he had made a little bonfire of his work before his death or shredded some manuscripts one day long ago – perhaps he did,” Bundy says. “It’s ultimately a good thing for artists to negotiate their own artistic destinies within the framework of the relevant laws. They have no more, and no fewer, rights than would you and I in the same situation.”

But lawyers who study the intersection of estate law and intellectual property say the issue is actually murkier. There is a long history of heirs substituting their own judgments for those of deceased artists and little case law about whether that is OK. Kafka, for example, asked his friend to burn his diaries and manuscripts, but the friend instead allowed publication of the writer’s unpublished novels; Eugene O’Neill did not want Long Day’s Journey Into Night published or performed until 25 years after his death, but his widow allowed it within three years; and Adam Yauch, one of the Beastie Boys, included a provision in his will barring the use of his music in advertising, but the provision’s validity was quickly questioned.

“It presents a moral and legal quandary,” says John Sare, a partner at Patterson Belknap Webb & Tyler and the co-author of Estate Planning for Authors and Artists. “You may feel a moral obligation to do as you’ve been asked, but that may be in competition with a moral obligation to do what’s best for the history of arts and letters and a legal obligation to conserve the assets of the estate for the beneficiaries.”

Eva E Subotnik, an associate professor at St John’s University School of Law, argues for some skepticism about such provisions. “There is something special about these kinds of assets,” she says. “They’re not just like a mansion or a fancy watch, but they’re socially valuable, and that has to play into the calculus. “I definitely argue against full-throttle enforcement of artistic control after death.”

But another expert on the subject, Lior J Strahilevitz, a professor at the University of Chicago Law School, disagrees. “Part of what we value in a great artist is not just raw ability but the ability to curate, and it’s frequently the case that artists build great reputations by being selective about what they show to the world,” he says. “It’s problematic to force Albee to share these plays when he didn’t think they were good enough.”

© The New York Times

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments