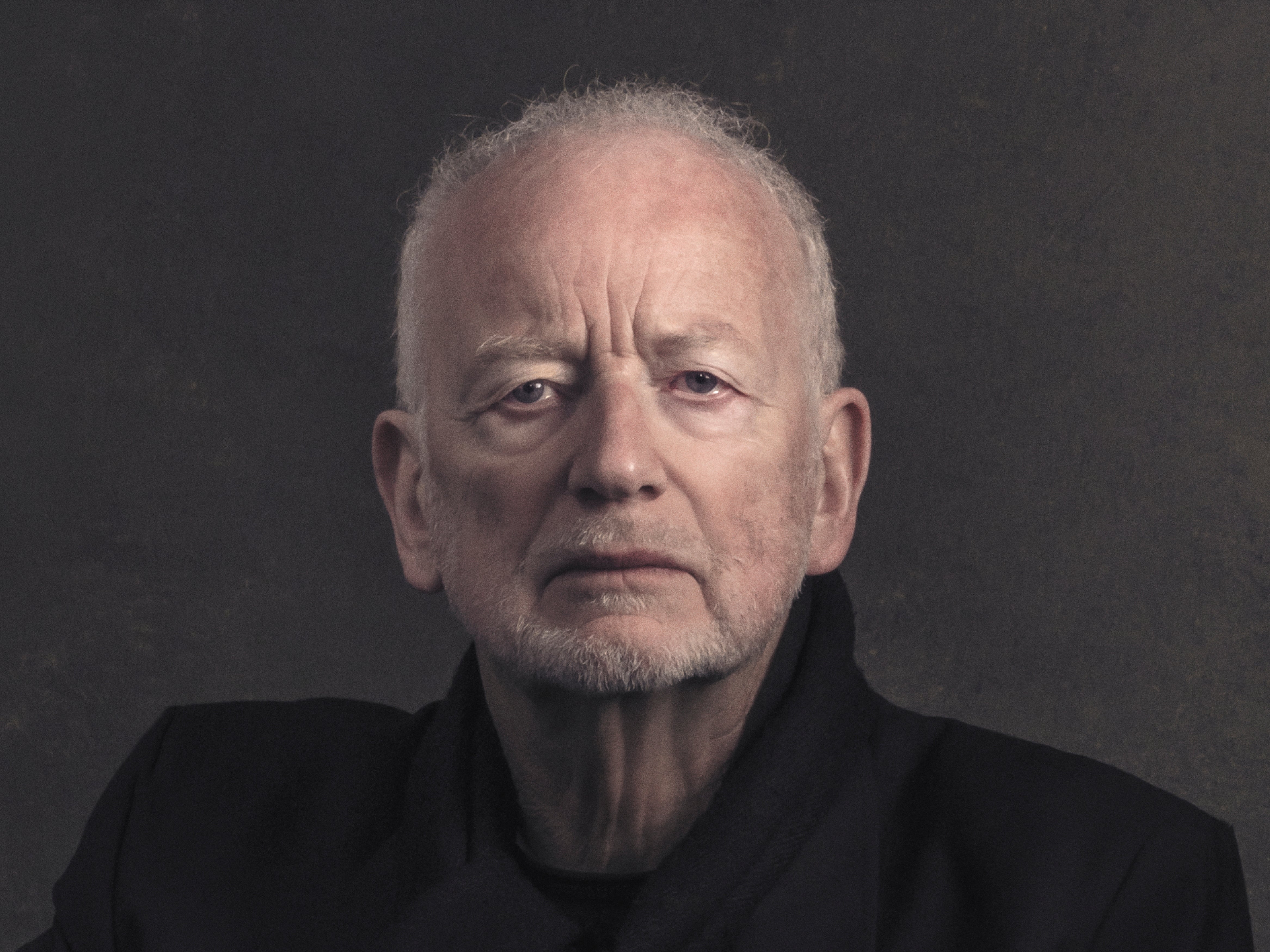

Ian McDiarmid: ‘Why should older people go quietly? We’ve still got things to say and things to do’

The Olivier-winning actor who plays Emperor Palpatine in the Star Wars series talks to Kate Wyver about the fight against ‘end-of-life serenity’, adapting Julian Barnes for the stage, and how he got his best-known role – ‘I’ve out-evilled Satan’

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Ian McDiarmid does not feel his age. “I feel younger,” the 77-year-old actor says. “People who are trying to be nice say, ‘Oh no, you look sort of...’ and I think, ‘Can I maybe get a 55? … in your sixties?’ OK, we’ll settle for that.”

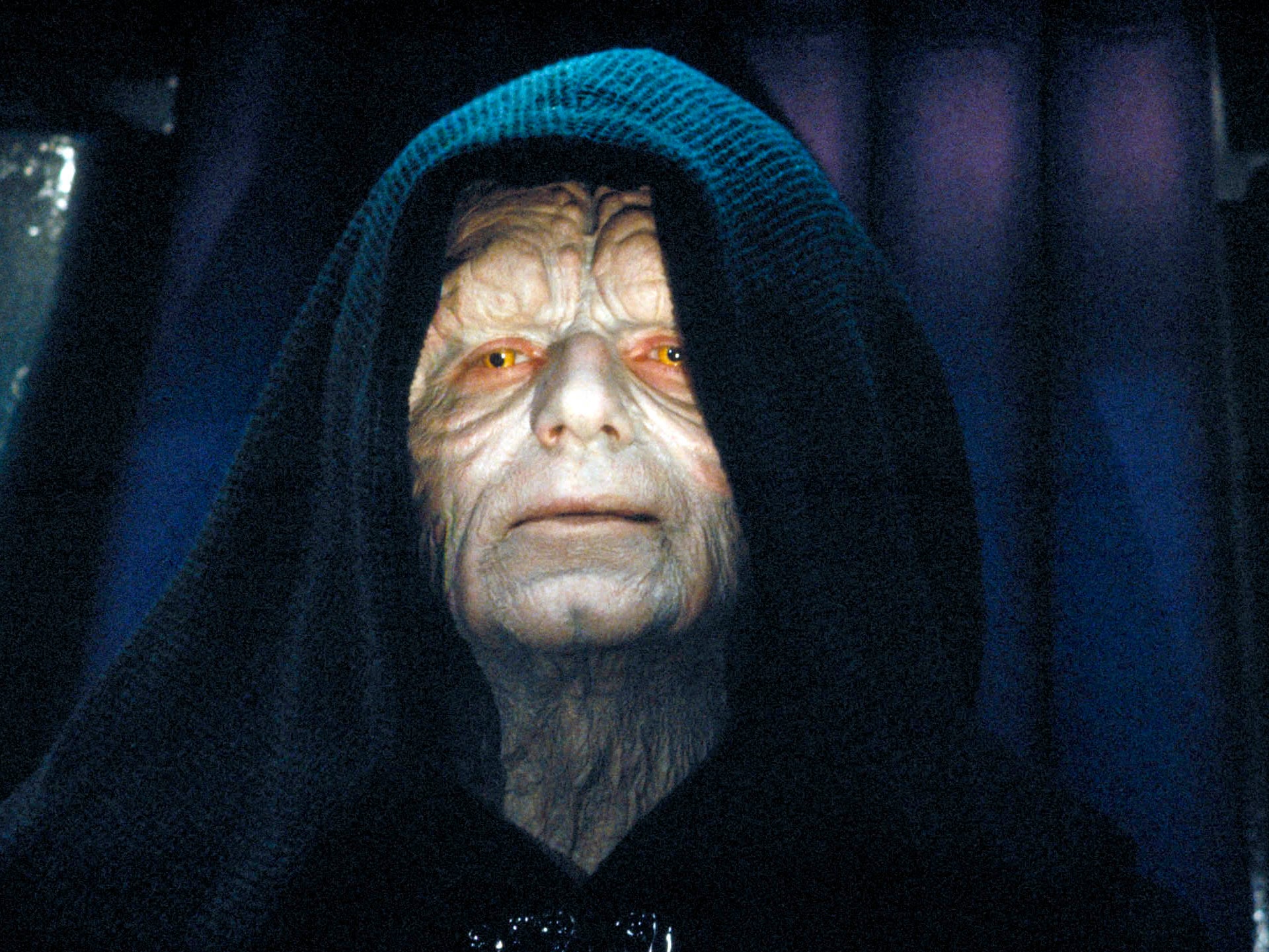

There’s an irony in this, because for decades McDiarmid has been known for playing a character much older than himself – the Emperor Palpatine in all three Star Wars trilogies, a role he first took on in Return of the Jedi way back in 1983, when he was still in his thirties.

To non-Star Wars fans, the Scottish actor is probably better known for his stage performances – he has both an Olivier and a Tony – and as a theatre director, having previously run the Almeida Theatre in Islington for 13 years. I catch up with him in an airy rehearsal room with a heavy wooden table and costume shots pinned up on a wall. He’s in rehearsals for The Lemon Table, a play made up of two short stories by Julian Barnes.

McDiarmid has adapted both pieces into monologues for the stage and will take the show, directed by Michael Grandage, on a regional tour throughout late autumn. Through the eyes of an ageing concertgoer and the composer Jean Sibelius at the end of his life, the stories take an unsentimental approach to death and old age. McDiarmid performs both parts, with the secondary roles – Sibelius’s wife (“gently reproving”) and the concertgoer’s ex (“he’s a real bitch”) – represented alongside him through clever lighting design.

Though playing roughly his own age in these monologues, McDiarmid has long been prematurely aged onstage. It was his ability to play an old man when he was young that bagged him the part of the blood-lusting emperor in George Lucas’s films. That, and some dodgy contact lenses. “Nothing is certain in the Star Wars universe,” McDiarmid cautions, but he thinks this is what happened.

Mary Selway, who had cast Raiders of the Lost Ark and would go on to cast Notting Hill and Withnail & I, had seen McDiarmid in Sam Shepard’s play Seduced at the Royal Court, playing an ageing version of the famously obsessive-compulsive American tycoon Howard Hughes. “I didn’t have a great deal of make-up,” McDiarmid says. “I was pale, I had a wig and fingernails. That was it. I guess Mary said to George Lucas, who at that time was looking for a very old person, ‘I know this guy who’s in his late thirties, but he could probably be convincingly old.’” The person who’d originally been cast couldn’t take the contact lenses, which were then made of glass, and put in by an optician aptly named Richard Glass. “George took Mary’s word for it.” McDiarmid shrugs. “I got in as a result.”

He met Lucas briefly for lunch. “Not over lunch, at lunchtime. He didn’t have time for lunch.” When McDiarmid got home, the phone was ringing, and he was told he’d got the part. “I said, ‘What’s the part?’” He mimes flicking through papers. “‘Apparently it’s called the emperor of the universe.’” He has played the role since Episode VI, reprising the cloaked figure for every chapter of the prequel trilogy, and then once again in 2019 for Episode IX – The Rise of Skywalker. “I like the fact that I am responsible in those nine films for everything bad that happens,” he laughs. “I think I’ve out-eviled Satan.”

As he gets older, McDiarmid believes less and less that people are either goodies or baddies. “Like Julian Barnes, I’m not sentimental about this. I don’t look for the good in people. I look to see what they’re really like, as far as one can judge. You hope that by and large people will tell you the truth. That’s one thing, as you get older, you cannot waste time with people who are deliberately blind or trying to blind others by not telling the truth.”

Long a fan of Barnes, McDiarmid first thought of staging the author’s work when he was asked to read The Silence for BBC Three. The 2001 short story traces the last years of Sibelius’s life, his drinking problem, the search for silence, and the pressure he faced to write his eighth symphony. McDiarmid’s reading was aired in the interval at a Proms concert, and he felt it had dramatic potential. Barnes wrote him an encouraging letter.

At the time, McDiarmid was co-running the Almeida Theatre in Islington with Jonathan Kent; he wondered if there would be a way to incorporate the piece into their annual contemporary music festival. But while Sibelius hadn’t died that long ago – he passed away, aged 91, in 1957 – he couldn’t be considered a contemporary composer, “so it fell away”.

When McDiarmid read The Lemon Table again a few years ago, he noticed another first-person narrative in the book, Vigilance. “There’s a sort of play between these two pieces about the nature of silence and the nature of relationships,” he says. “So I thought if I could string them together, I might make an entertaining evening of it.” He showed it to Grandage, wrote to Barnes, and planned to perform the two stories at the Edinburgh Festival. “We were all set, and then Covid happened. They did ask us back this year, but their spaces were mainly outdoor, and as this is primarily about silence, I wasn’t going to get that.” Instead, Salisbury Playhouse came on board and suggested co-producing a regional tour with Grandage’s company.

Both pieces are centred on music. While The Silence is a gentle exploration of loneliness and silence through Sibelius’s eyes, Vigilance sees a misanthropic man taking his hatred of people making noise during concerts to an extreme. “Everybody’s had a mobile phone go off,” McDiarmid says. “[British actor] Richard Griffiths, when he was performing in New York, once had a phone go off three times. So he said, ‘Right, you’re going now, and I’m going now too, and I will come back when this matter has been resolved.’” He laughs. “I’ve also seen a concert with Simon Rattle where he stopped at the end of a movement, turned to the audience, and said, ‘Please can you control your coughing. It’s impossible to do what I’m doing, which, you may not realise it, is often about creating silence.’” He doesn’t take such a direct approach to a noisy audience. “I’m one for continuing really, because you know the rest of the audience is on your side. I won’t answer back, but I think in character I could give them a really withering stare.”

The two plays are also, he says, about the benefits of silence. “I’m dead lucky because I’ve got a house in Scotland on the North Sea, where I go a lot.” He was born in Carnoustie near Dundee, and studied in Dundee and Glasgow, before moving to England, where he joined the Royal Shakespeare Company and directed at Manchester Royal Exchange, before moving on to the Almeida. “Lockdown for me was much easier than it was for many, many people. But even there, after a while, silence becomes oppressive rather than a delight. The sea and the birds can only take you so far after a year and a half – although they take me quite far. I didn’t really miss much, except people’s company.”

McDiarmid is a well-decorated performer, having won an Olivier (“It was called a SWET [Society of West End Theatre Awards] in those days, aptly named”) for playing The Professor – based on Albert Einstein – in Terry Johnson’s Insignificance, in which Marilyn Monroe (The Actress) walks into the scientist’s bedroom – the improbable situation hinted at in film star Shelley Winters’s autobiography. McDiarmid also won a Tony for his performance opposite Ralph Fiennes in Brian Friel’s Faith Healer in 2006, about the egocentric healer Frank Hardy; a play named by The Independent as one of the 40 best of all time. “When his narrative strays into descriptions of humiliation and loss,” The New York Times wrote of his performance, “the hurt breaks through the bravado like a fist through papier-mâché.”

McDiarmid has worked with Fiennes a number of times throughout his career, bringing him onboard at the Almeida when he was running it with Kent – a job he loved but doesn’t miss. “It was hair-raising while it lasted,” he says. “The thing about it being two of you, you can phone each other even at three o’clock in the morning, and go over how terrible it’s going to be, and how you probably can’t pay the wages at the end of the week, so what are we going to do?” He pauses. “That happened once.” His and Kent’s tenure was celebrated as vibrant and successful, with the theatre winning 45 awards under their leadership, and they were praised for bringing big names to a small theatre. “Glenda Jackson [who twice won the Oscar for Best Actress] said she’d come for 165 quid a week. It set a kind of benchmark.” They got Cate Blanchett for David Hare’s Plenty, Juliette Binoche for her British theatre debut in Pirandello’s Naked, Fiennes for Hamlet. “We kept being bolder and bolder,” McDiarmid says. “That’s what theatre needs to do now. People need to make big, bold choices. You want people to say you can’t get this elsewhere.”

Though he doesn’t have a list of what he wants to do next, he says “a big bold provocative new play” would do the job. “The old saying is: the essence of drama is conflict. I think the essence of drama is contradiction, with a good smattering of provocation for good measure.” His last play certainly caused a stir. In Chris Hannan’s What Shadows, McDiarmid played Enoch Powell, the Birmingham MP whose inflammatory 1968 “Rivers of Blood” speech appealed to anti-immigration feeling, and saw him kicked out of the Conservative shadow cabinet.

The Telegraph called the play “the most provocative theatrical act of the decade”, the BBC caused controversy by getting McDiarmid to read the speech on the radio to mark the speech’s 50th anniversary, and McDiarmid didn’t help matters by claiming that Powell was not racist – a remark he stands by. “That speech was there to do something, and he did it. He went out of the way to stir controversy, and I think, to draw attention to himself,” he says. “At the first performance, I thought there might be a lot of seats going up. But nothing happened, except the quality of silence was extraordinary.”

It’s safe to say The Lemon Table is less controversial. Its concerns are gentler and more straightforward, its first character distracted by the lives of others so that he doesn’t really deal with his own, the second focused on the matter of living when there’s not long left to do so.

McDiarmid himself has figured out how best to approach this stage of his life. “I am old,” he says reluctantly. “I’m made aware of that in little things, day by day. But I think the thing is not to surrender to it. I never describe myself as old. If I knock over something I say it’s not my age, it’s just me knocking over something. That’s how I’ll deal with it.” A few years ago, a heart attack left him feeling vulnerable, although he says he doesn’t like to go on about it. “You have terrified moments,” he says quietly. But, he insists, you can’t give in to them.

The stories in The Lemon Table have a similarly indignant attitude towards ageing. “Why should we go quietly?” McDiarmid says. “We’ve still got things to say and things to do. What I think he’s against in the book, and what the two plays are against, is a kind of end-of-life serenity. These people, whatever you think of them, are still fighting. They haven’t come on stage now to confess. They’ve come to assert, not to atone.” Towards the end of The Silence, Sibelius says matter-of-factly, “Cheer up! Death is round the corner” – a note the composer had written in his diary. “We all know it’s going to happen,” McDiarmid says, “and yes, it’ll be odd and strange when it does, and we want to avoid the pain. But it’s part of life.” For now, he says, “Let’s carry on.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments