Exhibition of Scottish art shows the characteristics of the artists work with wit, populism and colour

Forget the referendum: artists north of the border have already won the vote of Adrian Hamilton as 25 years of their past and present work goes on show

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Scotland is on a roll at the moment, although a visit to Edinburgh suggests that the excitement over the referendum may have peaked. Not in art, however. Inspired as much by the Commonwealth Games as politics, the summer has seen an immensely ambitious and rewarding effort to put on a display of Scotland’s art of the last quarter-century.

With an overarching title of Generation, it is being held in over 60 galleries, museums and special locations around the country covering everything from solo shows of new work to group exhibitions of past highlights.

Is the lady trying too hard? The simple answer is no. Scotland has had a fine tradition of home-grown and resident art for the last century and more. It has no need to boast or to strain to put itself on the map. It’s already there with a dozen or so winners and shortlisters for the Turner Prize and an art school in Glasgow that is one of the best in the world. What you see in this extraordinary exercise – too little noticed south of the border – is just how self confident and how international it is.

Strictly speaking Glasgow is the beating heart of contemporary art in the country, and long has been. But Edinburgh has the national museums and some of the best commercial galleries. With the annual Edinburgh Art Festival in full swing you get as good an entry into the artists and works as any. The starting point is the recreation in the National Gallery of Steven Campbell’s appropriately named On Form and Fiction.

First shown in Glasgow’s Third Eye Centre in 1990, it startled the art world then and still has the power to surprise today. Presented as a full museum room with benches and a musical soundtrack of Serge Gainsbourg and Jane Birkin’s infamous song “Je t’Aime”, the viewer is surrounded by walls covered with book illustration-styled ink and sepia drawings of magical and horror scenes. In the centre are a dozen large acrylic paintings on paper monumentalising some of the scenes suffused with Campbell’s particular interests in architecture, art and comics. Campbell, who died in 2007, grew darker with age and events. But this work from his most expansive years remains totally engrossing.

The curators see On Form and Fiction as a pivotal moment between the largely naturalistic painting of the previous generation and the installation and performance art of the younger generation. That may be in terms of its impact but installations of this sort, including by Campbell, had been going on for well over ten years by then. Far more telling was the sheer sense of energy and self assurance of the moment. If you had to look for characteristics that were particular to Scottish art of the last 20 years or so – and it’s always an artificial construct to do so – it would be in the wit, populism and colour of the work.

You see it most joyously in the exhibition of sculptures by Jim Lambie in the Fruitmarket Gallery in Market Street. Lambie, who takes the ordinary objects of diurnal life, and gives them new life and humour by the way he presents them, has taken his trademark “Zobop” floors of vinyl tape to cover the stairs and floor of the upper gallery in psychedylic colours that energize the whole space. “This is what I call art,” cried an eight- year-old, too young to concern himself with such abstractions and blithely ignoring the sign which admonished patrons “Do not touch. Please respect the work and keep children in hand”. That may be true as a means of protecting the potato sacks, leather jackets and record sleeves which Lambie re-arranges and paints over with vinyl to make them afresh but it rather runs counter to an art that invites you, in the best traditions of Arte Povere, to interact with the art on display.

The fascination with textures and everyday objects and how they can be used to redirect the eye of the beholder is a constant theme of these shows, the most persistent indeed. Alison Watt, who was Associate Artist at the National Gallery in 2006-8 and has an OBE to her name, does it breathtakingly with paint in her series of Folds from 1997, on display at the more extensive Generation rooms of the National Gallery of Modern Art. The paintings are just that, of the folds of fabric, monumentalised by scale, ultra-realistic in their Ingres-inspired precision and suggestive of person in their implication of the hand or body that has crumpled them. Quite, quite brilliant,

Whether this interest in fabric and diurnal objects is something special to women artists is a question that arouses a splendidly apologetic explanation by the curators of Karla Black’s polythene installation, even more tendentiously entitled Forgetting Isn’t Trying, Don’t Depend, At Base, Walk Away from Gilded Rooms. At Fault, Brains Are Really Everything. If you can get your minds round that mouthful, the curators add: “The artist’s regular use of pale pastel colours, in particular her fondness for baby blues and pinks, is not intended as a comment on gender.” Quite so.

Installation art gives rise to such flights, of course. Fortunately most of the actual works by Karla Black and others, in installation, video or performance, are not in need of explanation. Compared to the self-consciousness of some of the Young Brits to whom they might be compared, Scottish artists and those resident there are largely up front and imbued with a strong sense of the absurd.

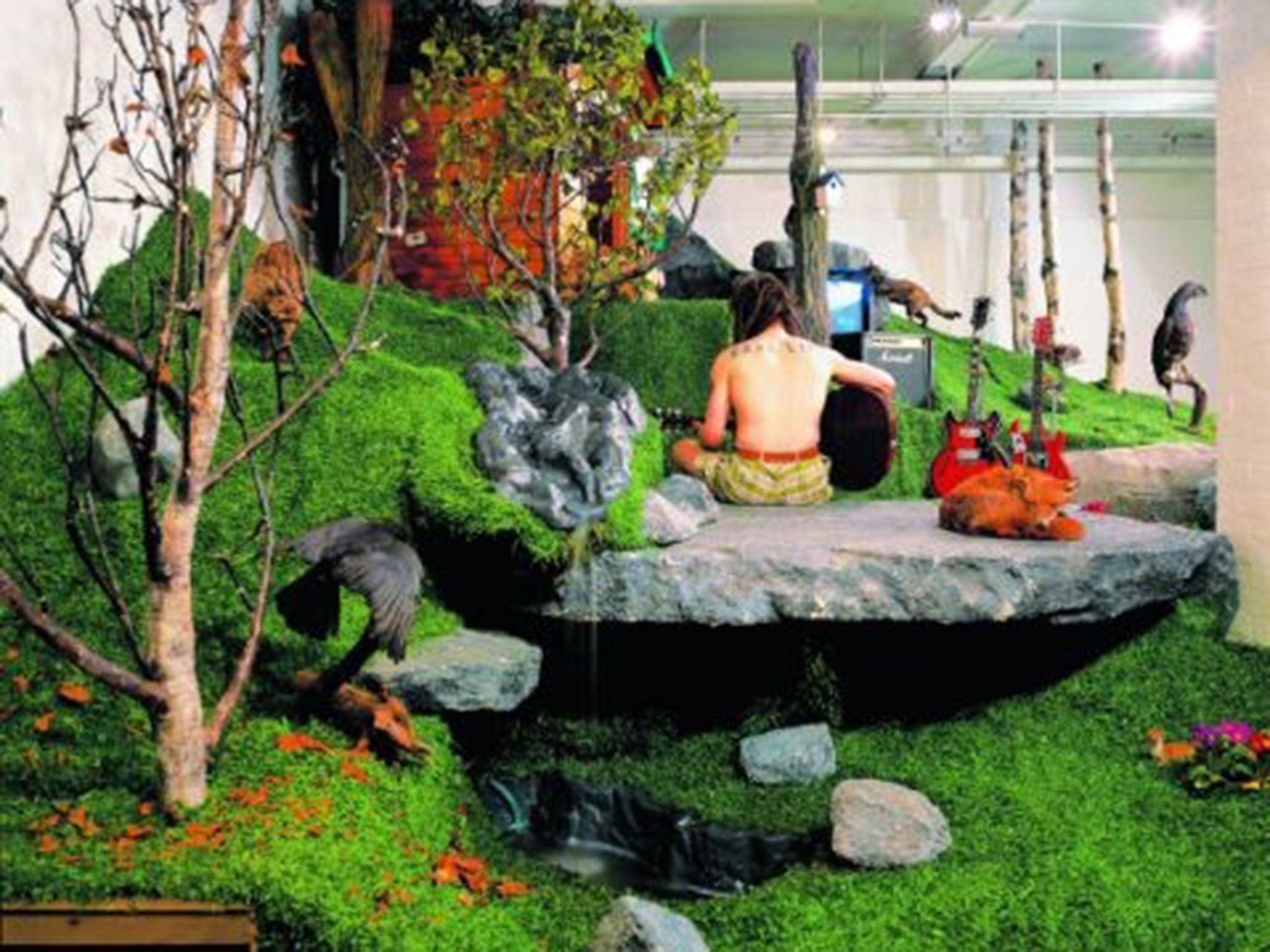

Works such as Ross Sinclair’s joyously kitsch immersive installation, Real Life Rocky Mountain,and the Turner Prize-winning Simon Starling’s grouping of object associations, Burnt Time, make their points with humour as well as humanity. So too with David Shrigley’s darkly humorous woodcuts and giant boots and Charles Avery’s detailed drawing of his imaginary town of Onomatapoeia.

What does strike one about Generation is how much of Scottish art is devoted to on-site installation, in which words, design and imagery are shaped to the ceiling, the stairwell or the room. Richard Wright, another Turner Prize winner, is justly known internationally for his site-specific paintings, as for the contempt of the art market which has driven him to destroying them as soon as they are painted. But his stairwell of the Museum of Modern Art has been preserved and is wonderfully refreshing in its use of space, line and image.

If one longs, amidst all this deliberateness, for a bit of old-fashioned socialist Scottish political assault, then you can find that at the City Art Centre, where a themed showing of art on architecture, Urban/Suburban, includes two coruscating videos of the post-war housing inflicted on the Scottish population. Graham Fagen’s Nothank interweaves the promotion film of a new housing complex with the less than complimentary comments of the inhabitants, while, with devastating effect, Nathan Coley’s overlays a visual tour of a suburban house with the commentary made for Corbusier’s modernist masterpiece outside Paris, Villa Savoye.

If you look to art to tell you something about art and place then what Generation is telling us is that Scotland is not suffering from an identity crisis or from introverted nationalism. It’s quite at ease with internationalism and itself. If only we could say the same about England.

Generation: 25 Years of Contemporary Scottish Art, Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh (www.nationalgalleries.org) to 25 January 2015; Scottish National Gallery, Edinburgh (www.nationalgalleries.org) to 2 November; ‘Urban/Suburban’ at City Art Centre, Edinburgh (www.edinburghmuseums.org.uk) to 19 October; Jim Lambie, The Fruitmarket Gallery, Edinburgh (www.fruitmarket.co.uk) to 19 October

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments