David Harewood: ‘If I had my breakdown in America, somebody would’ve shot me’

The British actor had £80 in his bank account when he was cast in ‘Homeland’ and his career changed overnight. He tells Alexandra Pollard why a racist and narrow-minded British TV industry forced him to turn to America

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.That was probably the start of my breakdown,” says David Harewood, rubbing his hands up and down the top of his head. “Understanding that I’d fallen for the subtle misconception that I could play anything, and do anything, and be anybody. Suddenly understanding that parts were off limits, and for no reason other than the fact I was Black.”

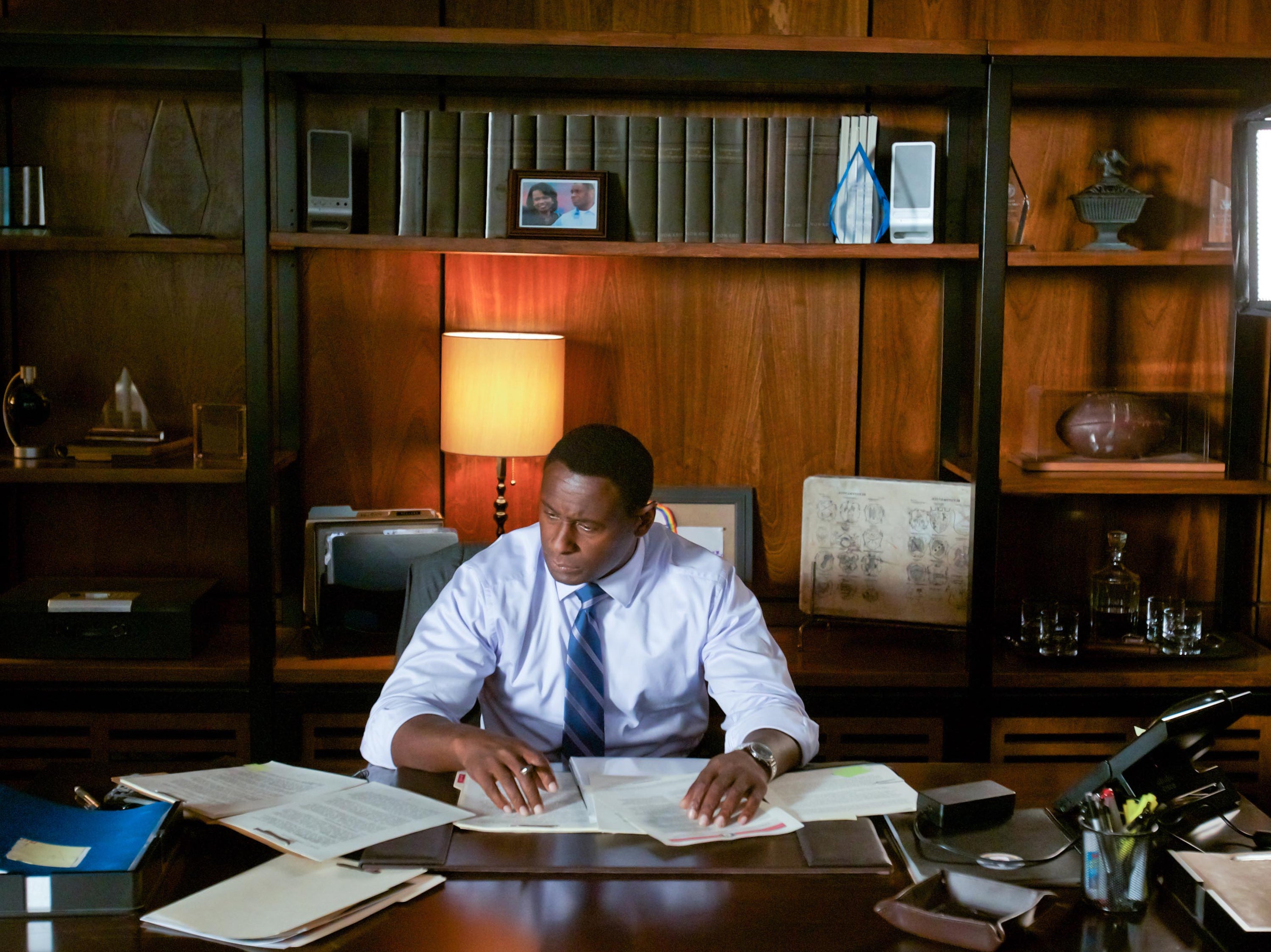

It wasn’t exactly a misconception. Over the past 15 years, Harewood has shown that he actually can play anything: spies, superheroes, warlords. He was Captain Poison opposite Leonardo DiCaprio in the Sierra Leone-set Blood Diamond, the shapeshifting Martian Manhunter in Supergirl, a US agent who flirts with Olivia Colman in The Night Manager. Perhaps most famously, he was Homeland’s formidable CIA director David Estes. But all of that only happened after he gave up on his home country and tried his luck in America.

“I couldn’t even get arrested in England,” says the 55-year-old. This is his first proper stint back in London in a decade. He’s between rehearsals for his new play, Best of Enemies, so we’re in the empty upstairs cafe of the Young Vic, Harewood taking big hungry bites of a croissant. Dressed in a black fleece zipped up to his neck, his face framed by thick black glasses, he is polite, incisive, but a little distant – he didn’t sleep last night, and I get the distinct impression he’s worried he’s bitten off more than he can chew. Somewhat improbably, he’s playing the white, ultra-right-wing political commentator William Buckley Jr – a role he wouldn’t have had a look in for when he first left Rada 30 years ago.

At drama school, he had played King Lear. After he left, he would have struggled to get cast as Lear’s fool. “I was seeing my white peers get lead after lead after lead after lead, turning work down for bizarre reasons like they didn’t want to film in Bolton,” he says with a sigh. “And I’m broke and getting offered two lines in some dodgy drama. And there’s no difference between me and them other than the colour of my skin.”

The experience dislodged long-buried memories of racism from his childhood in Birmingham. Memories of being hit in the head with a rock at the age of three; of white neighbours throwing bricks through the window and posting faeces through the letterbox; of an old white man telling him to “get the f*** out of my country, you little Black bastard”. Those recollections, combined with his career frustrations and a lot of marijuana, led to a breakdown – more specifically, a psychotic episode that led to him being sectioned when he was in his twenties.

He doesn’t remember much about the weeks that led to it, but he does know that he travelled around London talking to strangers and performing “street theatre”; that he heard the voice of Martin Luther King; that a casting agent witnessed him pacing up and down saying he was an alien. He ended up being restrained by half a dozen police officers. “I guess I’m just lucky that there wasn’t a stray elbow or stray knee,” he says. “There was six of them. Six. I was very lucky.”

He suspects that had it happened in America, he wouldn’t be talking to me now. “You only have to look online and type in ‘Black mental illness, police’, and you just see people getting shot, people getting tasered, people being really violently restrained. I was clearly disturbed for months. I think if I’d been doing that in America, somebody would have called the police and… f*** me, a large black man acting bizarrely? They would’ve shot me or tasered me. I don’t think I’d have made it.”

In the 2019 BBC documentary Psychosis and Me, which Harewood followed up this year with a memoir, Maybe I Don’t Belong Here, Harewood says that the breakdown made him a better actor. But when I mention that, he shakes his head. “I’m questioning that now,” he says. Everything feels different since he wrote the book, delving into his history, his breakdown, and the breakdown of his own father, who came to the UK from the Caribbean in the Fifties. “How do I put this? Coming straight from doing this” – he mimes ripping open his chest – “where I soul-search and peel all the layers back to suddenly putting all those layers back on and putting all these fake ones on… it’s been a lot tougher than I thought. Maybe I needed to have six months off. ” He laughs. “Maybe it’s because of who Buckley is.”

The play begins in the aftershock of Buckley’s infamous 1968 clash with Gore Vidal on live TV. The nadir of a series of nightly debates at the Republican and Democrat conventions, Vidal accused Buckley of being a “crypto-Nazi”; Buckley called him a “queer” before threatening to “sock you in your goddamn face”. The ratings were off the charts. The encounter is widely considered to have paved the way for adversarial political TV.

“I turned it down at first,” says Harewood of James Graham’s play, a co-production with Headlong Theatre, which was inspired by the 2015 documentary of the same name and opens in less than a week. “I just couldn’t see it. A white, conservative, right-wing politician? It didn’t make any sense.”

It was Kwame Kwei-Armah, the Young Vic’s artistic director, and the play’s director Jeremy Herrin, who persuaded him that it would be “fun”. It helped that the Sewell Report had just come out, a government-commissioned report which concluded that Britain does not have a problem with institutional racism, and in so doing denied Harewood’s lived experience – and that of millions of others. “I saw how some of the Black people selling that were just talking garbage,” he says. “And I didn’t think it was that much of a stretch that people who look like me would have those politics. You’ve got people in the current administration, the Kemis and the Kwasis and the Pritis” – that’s Tory MPs Kwasi Kwarteng, Kemi Badenoch and Priti Patel – “who espouse that sort of politics.”

Once he’d been talked into it, though, he realised what a big undertaking it would be. “First of all there’s an enormous amount of lines. I found that quite tough. And now the politics are starting to sink in and… f***.” He wonders whether he’s made Buckley too sympathetic. “Because I’m affable, charming, people like me… those lines coming out of my mouth is strange. You find yourself going, ‘Oh I agree with you.’” Himself included. The other day, he ran through one of Buckley’s particularly egregious speeches with his voice coach. “At the end of it, she said, ‘God he’s a f***ing awful man.’ It jarred with me, because I’ve gone that far to see his perspective. I have crossed the river to play this man. But there’s a bit of me that keeps going, ‘Hang on a minute. Who the f*** is this guy?’”

Maybe it’s important to understand the other side’s point of view – although sometimes I find that hard. “Absolutely,” says Harewood. “It is important that we do that, but it’s really difficult because there’s so much hate. I can’t listen to [Nigel] Farage. I can’t listen to [Boris] Johnson. I can’t listen to most Tories. But working-class people are. Having been in America for 10 years and come back here, I simply don’t recognise the place. I don’t recognise what’s happened to the left – people seem to have fallen out of love with it. I just can’t understand how people vote against their own interests. They have fallen hook, line and sinker for lies.”

That decade in America began with Homeland. The show, about a former prisoner of al-Qaeda (Damian Lewis) who may or may not have been turned by the enemy, and the bipolar CIA officer (Claire Danes) who becomes obsessed with him, was a phenomenon. It won Golden Globes, Emmys, praise from Barack Obama. The taut, explosive first season – one of the greatest seasons of television ever made – topped most “best TV” lists that year. At the end of the second season, Harewood’s character (spoiler alert) was killed by a bomb, which was probably for the best – the show somewhat jumped the shark after that.

“I had 80 quid in the bank when I got Homeland,” says Harewood. “I was broke. I hadn’t worked in nearly a year. And from being at my lowest ebb to winning an Emmy and going to the Golden Globes… it was literally from my lowest to my highest point.” He doesn’t think it would have happened if he had stayed in the UK. “It’s just difficult to achieve in this country,” he says. “Even now, you turn the TV on and there’s still not that many… I mean there’s a lot of diversity on TV but it’s sort of random and sporadic. There’s no shows with leading Black actors still. Two or three, even in my life. Whereas in America, there’s a whole host of shows with leading Black actors.”

He hasn’t worked much in England since then. “My career’s exploded in America. It’s nice to be getting in rooms that I wouldn’t normally get in, and be courted and respected. I get straight offers, which is not something that I got when I was here. I was still having to audition. F*** that. F*** off.” Even after Homeland? “There was one post-Homeland thing that I had to read for, and I just said ‘No, tell them to f*** off. I don’t need it.’”

Why does he think the UK is so behind America? “That’s the thousand-dollar question,” he says. “I think executives and audiences are very literal. Everything has to look like this and be like this, fit into these regimented boxes. It’s surprisingly difficult to break that. You know, you’ve got the Conservative MP being threatened by a woman playing Doctor Who...” A few weeks ago, during a debate in the House of Commons, Tory MP Nick Fletcher declared that “female replacements” in shows like Doctor Who were robbing young men of role models, hence why they are turning to crime. “When there’s a whole f***ing host of male role models in Marvel and DC,” says Harewood. “It’s just ridiculous.”

He believes bigoted attitudes linger for generations. Take blackface: for a while, it was one of the most popular forms of entertainment in Britain. “They were the biggest shows in the West End in the 1800s,” explains Harewood. “Shows like James and the Giant N*****, Billy and the C****... Huge, packed audiences. At the same time, you’ve got the American civil rights leader Frederick Douglas coming to London and people saying, ‘You’ve got to tone down your intelligence because people think Black people are like that.’ That stuff perpetuates. Intelligent, strong Black people really get up people’s noses. Particularly Black women. Meghan. People really don’t like it.” And yet most people are in denial. “The amount of times I see white people go, ‘It’s not racist.’ What the f*** do you know? When was the last time you f***ing experienced it?’.”

He was relieved, then, that when he met the Earl of Harewood recently, whose direct descendant enslaved Harewood’s descendants, the earl fully accepted his family’s history of racism. “He has done a lot of work to make amends – giving articles that he found in the house back to Barbados; running bursaries for local black school kids to go to college. What he said is: ‘I’m not responsible, but I can be accountable.’”

Harewood’s great-great-great-great-grandparents were named Harewood by the people who enslaved them. And because there were no records kept of slaves until emancipation, he doesn’t know what his ancestors were called before that. The name Harewood, he says, “sits uncomfortably as I get older. I’ve spoken about it with my kids.” He has two daughters with his wife, Kirsty Handy. “If they wanna change it, it’s completely up to them. Because it’s not ours. I have it, but it’s not mine.”

He’s done his ancestry DNA. It told him he originated in Benin, on the west coast of Africa. “One day I’ll go there,” he says, “and meet some elder. They’ll give me a name.”

‘Best of Enemies’ is running at the Young Vic until 22 January

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments