Benedict Cumberbatch has 1,480 lines in Hamlet - so what's the secret to actors' memory skills?

Benedict Cumberbatch has to remember 1,480 lines to give his new 'Hamlet'. An orchestra is performing a whole symphony by heart for the Proms. How do they do it, and why is it so good for their brains –and ours? Boyd Tonkin elucidates

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference."Remember me!" At midnight, on the battlements of Elsinore, his father's restless spirit transfixes Hamlet with that command. "Remember thee!" Hamlet reflects: "Ay, thou poor ghost, while memory holds a seat/ In this distracted globe." Summoned to vengeance, the Prince of Denmark decides that in order to fulfil his mission, he must clear out his memory-banks. He should erase all the knowledge installed by an elite Renaissance education: "I'll wipe away all trivial fond records,/ All saws of books, all forms, all pressures past,/ That youth and observation copied there".

The duty of revenge means unlearning all that Hamlet knows by heart – a big deal, around 1600. In the second act, memorisation again becomes a plot-pivot. Hamlet writes a speech for the First Player which, he hopes, will terrify stepfather Claudius into admitting guilt: "You could, for a need,/ study a speech of some dozen or sixteen lines, which/ I would set down and insert in't, could you not?" A cinch. In the London theatre Shakespeare knew, star performers had to commit bulky parts to memory within days. Richard Burbage, for whom he probably wrote Hamlet, was a legend for his repertoire of supersized roles.

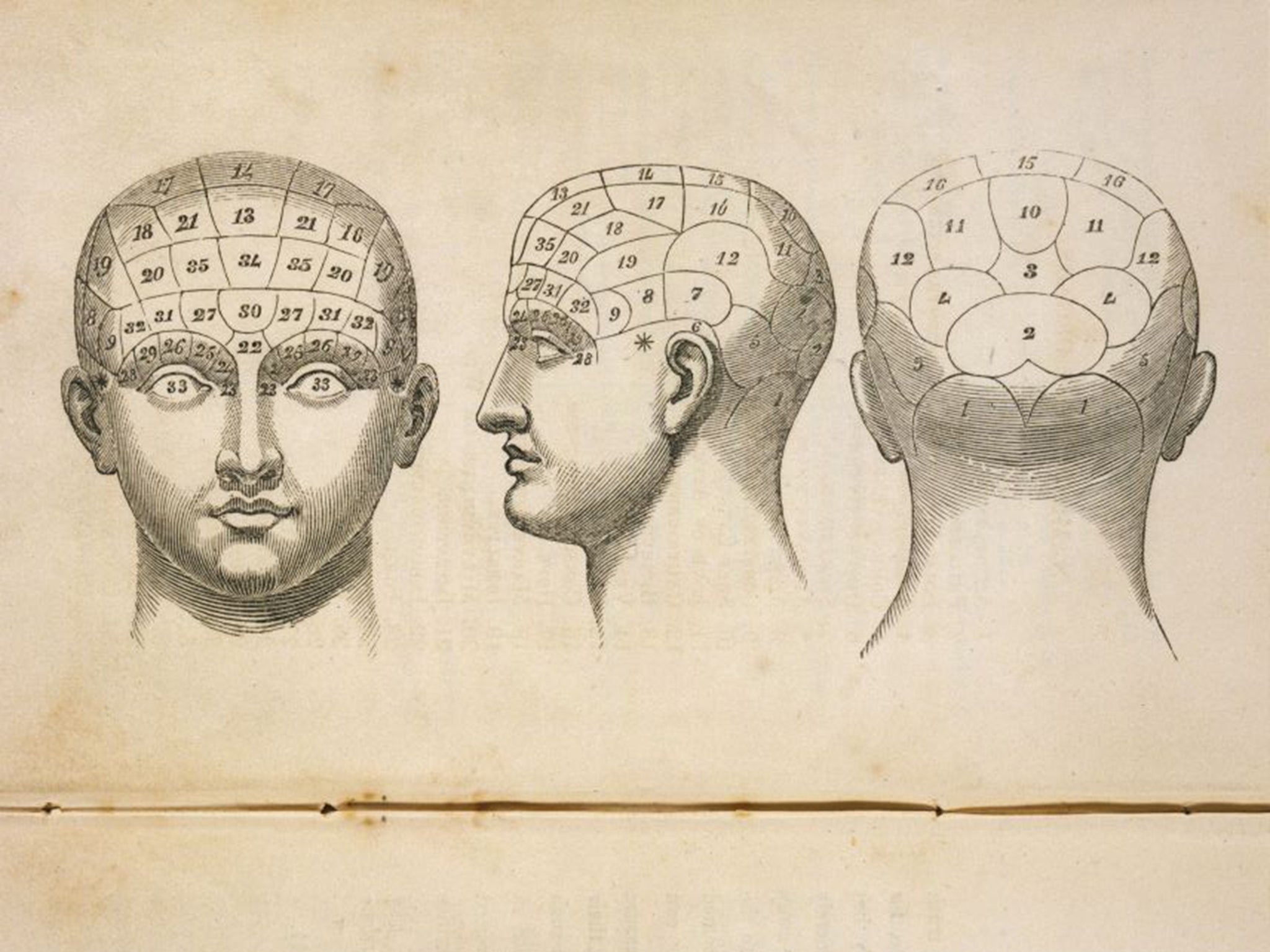

Next week, 415 years on, Benedict Cumberbatch will become the latest actor to scale the peak of Hamlet when he begins his sold-out run at the Barbican Theatre in London. Every Hamlet has to learn, and repeat night after night, around 1,480 lines. The count will vary a little according to the edition used. Compared with this epic stretch, Shakespeare's other tragic leads look almost lightweight: Othello with 890, King Lear 750, Macbeth a slimline 710. If Hamlet stands at the pinnacle of the actor's art for its emotional and intellectual range, it also activates and exercises the hippocampus – the area in the brain that converts short-term into long-term memory – as few other roles ever will.

For civilians, the feats of large-scale memorisation that actors and musicians routinely accomplish remain a mystery and a marvel. In another art form, this Sunday the Aurora Orchestra and its principal conductor, Nicholas Collon, will perform Beethoven's sixth symphony, the Pastoral, entirely from memory at the BBC Proms. This concert follows the acclaim that greeted a similar gig at last year's Proms, which saw the Aurora play Mozart's 40th symphony without scores. Collon writes that the event "ranked as one of our most intense and rewarding musical experiences. In every way it deepened and enriched our relationship with this extraordinary piece of music, forcing us to internalise nuances that can be easily glossed over when reading from the page."

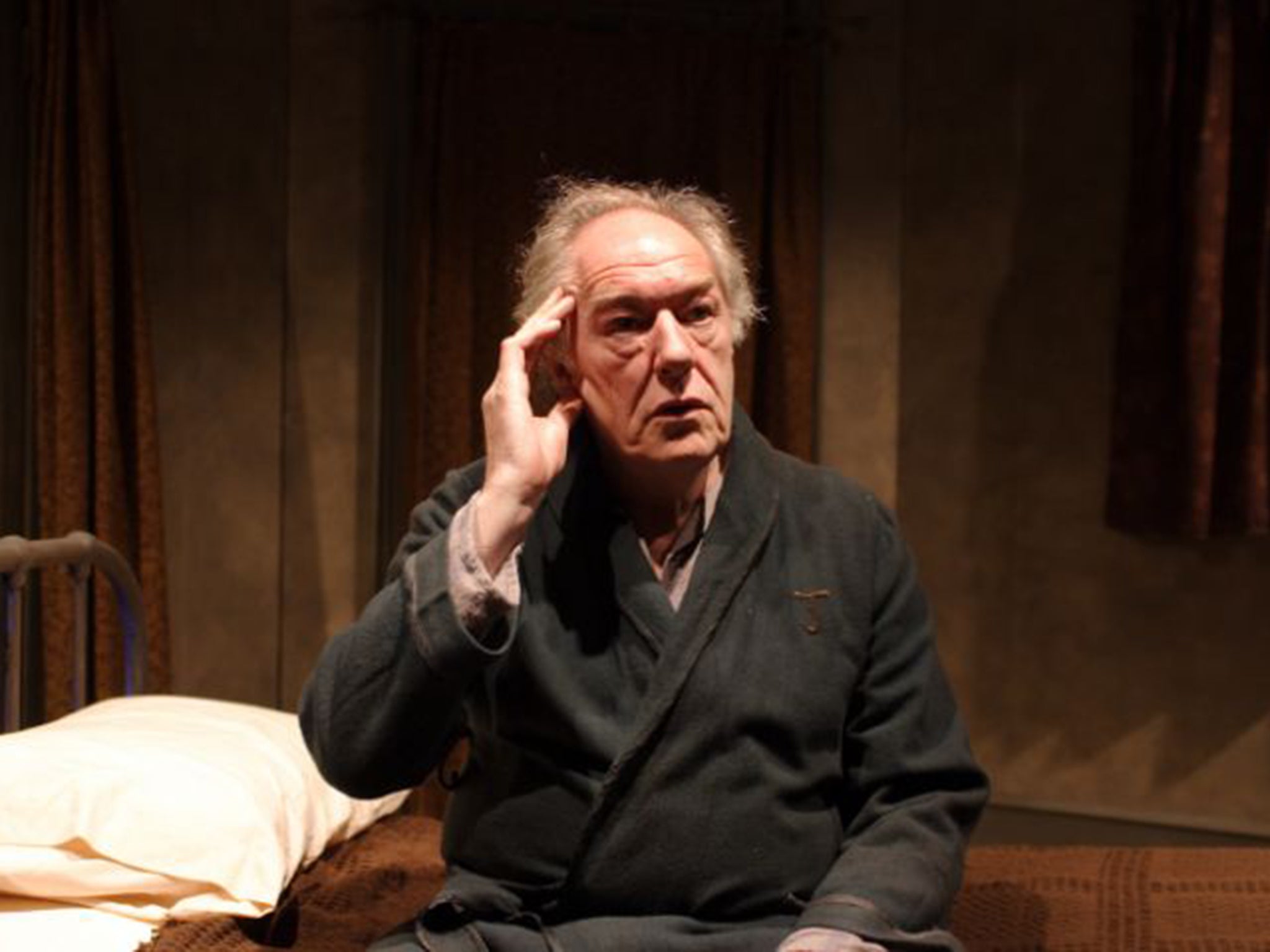

We don't take this heroic level of recall and retrieval on trust in the theatre and the concert-hall alone. The humble hotel-lounge pianist will often know hundreds of pieces by heart, as will the folk singer. The questions "How do they do it?" and "Could everyone do the same?" sound painfully jejune. Yet they fascinate lay people. The actor Michael Pennington was a distinguished Hamlet for the RSC in the 1980s, celebrated for his intelligence and clarity. Since then he has not only practised his art but dissected it in a series of incisive books. "It is the question that everyone asks at a party," Pennington says about the everyday miracle of learning and retaining lines. "It defines the job; it's the bare necessity. But it's still the thing that amazes other people."

Learning by heart continues to thrive in many cultures. Islamic custom cherishes the achievement of the "Hafiz" – the guardian – who can recite from memory every verse of the Koran. Scholars suggest that Homer's Iliad and Odyssey crystallised in their written form around 750BC, out of an already ancient school of oral transmission. In Serbia, as late as the 1930s, the Homeric investigator Milman Parry came across folk bards who could recall, and embroider, traditional stories thousands of lines long.

In the West, however, what was dismissively labelled as "rote learning" began to fade from public education early in the 20th century. For all his back-to-basics rhetoric, Michael Gove's reforms to the GCSE syllabus did not reinstate mass recitation in the classroom, though they do insist that pupils should know well "no fewer than 15 poems". Meanwhile, the Poetry by Heart competition begun in 2012 by former Poet Laureate Andrew Motion this year encouraged pupils from 333 schools to rekindle the ancient art – not as an empty ritual, but as a creative means, argues Motion, of "finding pleasure and confidence in a part of the curriculum where such things can be in short supply". The 2015 national winner was Emily Dunstan of Graveney School in Tooting, who performed poems by Elizabeth Bishop, John Keats and Siegfried Sassoon.

So actors and musicians use – admittedly, at an extraordinary pitch – a near-universal facility that just happens to have fallen out of favour. And the more you hear any text, the easier it becomes to ingest for good. Michael Pennington reports that, when he first studied Hamlet as a professional actor, long years of exposure to the play meant that the part posed no special problems. "By that time, I'd heard it played over and over again, in my mouth and other people's mouths. I hardly had to learn it at all." In contrast to the abstractions and complexities of, say, King Lear or Macbeth, he also found that the punch and snap of Hamlet's own speech helped to make the role stick. "Although it's very long, the language is surprisingly simple to learn – it's very practical, down-to-earth language. What could be simpler than 'To be or not to be ...'?"

Do actors and musicians command a special treasury of recall-and-retrieval secrets – dark arts invisible to awestruck spectators? Almost certainly not. When the leading Shakespeare scholar Professor Peter Holland researched memory and forgetting on the stage, he wrote that: "What I found most remarkable is the virtual silence in the books on actor training on how to remember the lines". By and large, that's still the case. Handbooks of technique will briefly round up useful tips but then move on to website management or the benefits of yoga.

For most performers, the mantra remains what Pennington calls "Repetition, repetition, repetition". Yet that discipline can take a myriad of forms. One size of memorisation by no means fits all. Pennington says that "I always learn late at night. Some people prefer the morning, when you're fresh .... Everyone has their own system, especially when they come across passages that are particularly tricky for them." He recommends acrostics and mnemonics that associate troublesome passages with a memorable story: an approach rooted in the Renaissance "art of memory" that flourished in Shakespeare's day.

Recordings of a single part or of an entire play, committed to MP3 players and listened to over and over again, also find favour. This record-and-repeat method has a long pedigree, but Peter Allday's LineLearner app brings it into the download age. Older forms of technology also have their fans. Lenny Henry speaks for many actors when, in Laura Barnett's book Advice from the Players, he advises: "Try writing down your lines, at least 10 times for each scene." Moving around also helps to fix the words. It seems that the hippocampus likes to have other senses busy while it works. Helga Noice, professor of psychology at Elmhurst College in Illinois, discovered that the physical actions that partner words have a crucial effect in sealing the deal for long-term memory.

All actors agree, however, that the key to mastering lines is not to treat them as lines, but as the ingredients of a character and a story. Grasp the total meaning, and the words will swiftly follow. For Michael Pennington, "You come to know the character that much better. It's like the engineering of a car: you get to see what goes on under the bonnet. It's a matter of cosying up the author – you see how they do it, and you develop a feeling for the music of the language".

That "music" will often serve as Super Glue for memory. As anyone who knows the simplest poem by heart will recognise, we seldom remember via micro-units of sense but through chunks, phrases and patterns, often hammered into place by metre or by rhyme: "Tyger, Tyger burning bright,/ In the forests of the night:/ What immortal hand or eye,/ Dare frame thy fearful symmetry?..."

Over in the musicians' rehearsal room, parallel rules apply. At this year's BBC Proms lecture, neuroscientist and former rock producer Professor Daniel Levitin – author of This is Your Brain on Music – outlined the processes of prediction, recognition and comparison that allow listeners to hear music and performers to reproduce it. A region of the frontal cortex known as Brodmann 47 helps us to understand musical patterning. This inner ear for chunks, lines and sequences will ease the path of singer and soloist. Levitin even suggested that the shape-making capacity of the brain means that Brodmann 47 may be "fundamental to the survival of the species: the ability to predict what's going to come next".

As with those actors who learn via gesture and movement, Levitin reports that "motor memory" also plays its part. Fingers and arms will recall what they did before, and how they did it, in a known piece. "It's the same mechanism that keeps us from falling off a bicycle." Meanwhile, all that predictive activity in Brodmann 47 sensitises musicians to the chords, sequences and scales within a given form. That will work for music that sticks to the harmonic norms. But how much Stockhausen or Boulez could you confidently learn by heart?

On Sunday, Nicholas Collon and the Aurora players will tackle from memory the 40-odd minutes of Beethoven's Pastoral. As the conductor acknowledges when I talk to him during a break between rehearsals, "This is never going to be a very easy or practical thing to do. No beating about the bush: it's a big job." Singers and soloists, he notes, will frequently master recitals, concerti and operas that call for a prodigious exercise of memory. For full-size orchestras and entire symphonies, however, the scoreless performance remains a rare bird.

The Aurora's triumph with memorised Mozart convinced him of its value. "It was an experiment, but it was such a joyful process .... Everyone was immersed in the music in a much deeper way. It forces you to learn the structure of the piece," right down to the tiniest details. "You actually have to embody every note." Collon adds that, "There's one very obvious benefit: the visual communication between the orchestra and the audience. There's no barrier between them – no music stands." For him, the expressive quality of a scoreless concert matters far more than the element of high-wire act without a safety net: "I have tried to get away from thinking about this as a feat or as a challenge." Rather, "It gets you thinking about the music in a different way".

However much we know about the universal endowments of the brain, a sense of mystery still lingers. With that comes the ancient dread of forgetting. Peter Holland cites a story about the great 18th-century Shakespearean actor Charles Macklin. One night, when he was already in his late eighties, after more than half a century of playing Shylock, Macklin dried on stage. The beloved veteran turned to the audience to apologise, for "a terror of mind I never in my life felt before. It has totally destroyed my corporeal as well as mental faculties."

Every performer will carry a fragment of that terror – even Cumberbatch, when, with a mountain in front of him, he first whispers, "A little more than kin, and less than kind." Michael Pennington says: "It's vast. It's huge. A real nightmare – it's like falling at Becher's Brook." In fact, audiences will often overlook slips and lapses: "I've heard people deliver five or 10 lines of made-up blank verse before they get back on track. But it's still what we most fear."

Age does make a difference. For Pennington's acclaimed King Lear in New York in 2013, "I had to take precautions". Lines that in youth adhere effortlessly have to be chased, captured and securely locked down. In his recent book about playing Falstaff, Year of the Fat Knight, Antony Sher recalls how he used to scoff at the naïve playgoer's query, "How do you learn all those lines?" Now, "I've stopped laughing. It's an age thing." Earlier this year, Michael Gambon revealed that he has given up stage roles because of creeping memory loss: "It's a horrible thing to admit, but I can't do it. It breaks my heart."

Such a cri de coeur ought to remind us how much we take for granted. Every night, we expect art, practice, training, teamwork and trust to fuse seamlessly into a note-perfect or line-perfect rendition. "I don't know how it's done," muses Michael Pennington. "It just becomes as normal as breathing." In the meantime, those of us who never hold a tune or tread the boards could still do more to keep that hippocampus happy. Pennington notes that the actor Dame Gwen Ffrangcon-Davies, who lived to the age of 101, never ceased to commit fresh lines to memory. "She would learn a new piece of poetry every day until she died. It has got to be good for the brain."

'Hamlet', with Benedict Cumberbatch, runs at the Barbican Theatre 5 August-31 October, with live transmission to cinemas nationwide on 15 October. BBC Prom 22, with the Aurora Orchestra and Nicholas Collon, is at the Royal Albert Hall at 3.30pm on Sunday 2 August, with a BBC4 broadcast on Sunday 9 August. Michael Pennington's book 'Let me Play the Lion Too: How To Be an Actor' is published by Faber & Faber. He will be appearing in the Kenneth Branagh Theatre Company's production of Shakespeare's 'The Winter's Tale', which opens at the Garrick Theatre on 17 October

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments