Andrea Dunbar: The short, troubled life of the prodigal Bradford playwright

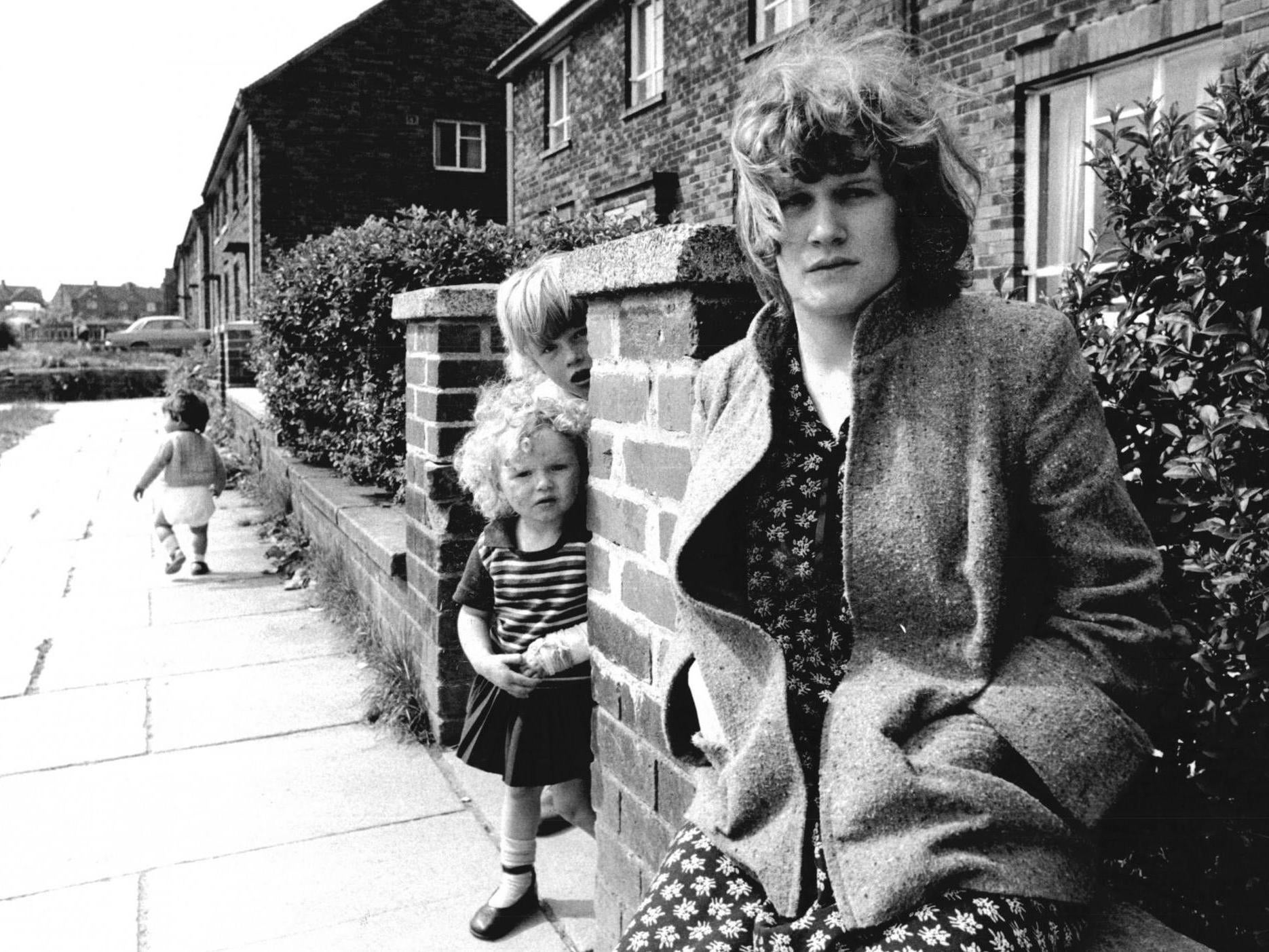

Dubbed a ‘genius straight from the slums’ prior to her death at the age of 29, Dunbar led a difficult life. As the new play about her life, ‘Black Teeth and a Brilliant Smile’, tours theatres, Alexandra Pollard explores her complicated legacy

This is my story,” says Andrea Dunbar (Emily Spowage) in Black Teeth and a Brilliant Smile, a new touring production based on the troubled playwright’s short life. “Not yours, not anybody else’s.”

It is a necessary assertion. The working-class prodigy – problematically dubbed “a genius straight from the slums” – had her life and career co-opted, fetishised and exploited throughout her 29 years. Celebrated, too, but at a cost. A heavy drinker, she died in 1990 a few months shy of her 30th birthday, leaving behind three children and three completed plays.

Since then, Dunbar’s legacy has waxed and waned. But though her plays are out of print and rarely performed, fascination in Dunbar’s story has reignited of late. Indeed, following a successful revival of Rita, Sue and Bob Too at the Royal Court last year, not only is Lisa Holdsworth’s Black Teeth and a Brilliant Smile (based on Adelle Stripe’s novel of the same name) set to tour the country once it finishes its residency in Bradford on 8 June, but a new Radio 4 drama based on Dunbar’s life, Rita, Sue and Andrea Too, will air on Friday.

Born and raised on the Buttershaw council estate in Bradford, Dunbar wrote her first play, The Arbor, as a school assignment at the age of 15, around the same time she became pregnant and gave birth to a stillborn baby. She had no clue then that her homework, scribbled in green biro on pages torn from an exercise book, would be performed at London’s Royal Court Theatre three years later.

The Arbor tells the story of a Bradford schoolgirl living on a racist estate with an abusive, alcoholic father. The girl falls pregnant after being coerced into sex by her Pakistani boyfriend, and the play’s dialogue is insightful and unflinching. “You shut your mouth or do you want a punch in the teeth?” her father says when he discovers she’s pregnant. “That’s all you’re f**kin’ fit for isn’t it?” she shoots back. “Yes, belting women.” It was, rather unsubtly, cribbed from Dunbar’s own life; the protagonist, written as “Girl” in the stage directions, is referred to as Andrea by her fellow characters.

By the time theatre director Max Stafford-Clark stumbled upon the play, after Dunbar entered it into a national writing competition, the 18-year-old had a baby daughter, Lorraine, and – just like her protagonist – was living in a refuge for victims of domestic abuse. Stafford-Clark tracked her down. “Andrea was taciturn and ungiving,” he wrote, somewhat loftily, in Taking Stock: The Theatre of Max Stafford-Clark. “She had watchful eyes and a strong chin. She received the news that we were to produce her play at the Royal Court with no particular enthusiasm.”

By the time her play was in production, Dunbar had mixed feelings. “She enjoyed rehearsal,” recalled Stafford-Clark, “and was amazed to find how much she laughed at the scenes she had written. ‘It weren’t so funny when it were happening,’ she commented...” But she was also distracted by her dire living situation. She wasn’t paid much for the supposed honour, and what she was given had to be sent surreptitiously lest her father steal it. “And life kept taking priority over art: there was a row with her boyfriend; her daughter Lorraine was poorly; there was a court appearance for assault; the windows had been put out after a row with some neighbours.”

Still, the play was a success, and Dunbar was swiftly commissioned to write a follow-up. The result, Rita, Sue and Bob Too, the troubling story of two teenage girls having affairs with the same married man, was also semi-autobiographical. It caught the attention of director Alan Clarke, and a film version was soon underway. But it was not a happy experience for Dunbar. She was banned from the set, even when they were filming outside her own house, and Clarke brought in a team to re-write large sections. The ending was changed so that the two girls, so clearly groomed by Bob, ended up going back to him. Black Teeth and a Brilliant Smile dramatises Dunbar’s horror at this. “It’s not f**king real,” shouts Dunbar, played by Emily Spowage as an adult, and Lucy Hird as a teenager. “Bob should be left with nothing. Listen to me! You don’t go back to someone who’s rejected you. They’d never go back to Bob.”

The film – released with the tagline “Thatcher’s Britain with her knickers down” – was met with positive reviews from critics, and horror from the people of Dunbar’s hometown. They saw her as a traitor for depicting Bradford in such an unkind light. On one occasion, according to an interview with her daughter Lisa Pierce years later: “She was sat on a bar stool in the Cap & Bells pub. I had just come out of school when this person we knew just dragged her off the stool by her hair and threw her to the floor and then walked out.”

Dunbar claimed not to be bothered by her neighbours’ vitriol – “If they are attacking me they are leaving some other poor bugger alone,” she said in an interview, “I can take it” – but she was deeply rattled by the situation. She was bothered, too, by the fact that she was being forced “to perform her identity as an impoverished and unlikely genius” to middle-class theatre-goers and critics, as Girls creator and star Lena Dunham observed in a piece for her feminist newsletter Lenny Letter.

After her third play, Shirley, Dunbar’s inspiration dried up. She was an apparently neglectful, sometimes deeply unpleasant, mother to her children, having succumbed to alcoholism (her daughter Lorraine, who was later convicted of manslaughter after her own child ingested a lethal dose of methadone, claimed that she once overheard her mother saying she didn’t love her as much because she was mixed race). She seemed to have become disillusioned by writing, too. “The dreams I had are all finished,” she said at the age of 26. “There were just one thing – as a kid, I always thought, ‘One day, I’ll be on telly.’ I was, and after that, it were gone.” In December 1990, she collapsed in her local pub, and died of a brain haemorrhage.

Nearly 30 years on, though, Dunbar remains an inspiration. “She’s still a symbol of something to a lot of writers,” said Lisa Holdsworth, who went to a comprehensive school in Leeds and got her first break writing an episode of ITV drama Fat Friends, in an interview with the i. “A symbol of – it can be done, perseverance will pay off, and your voice is just as important as someone with 15 degrees and all those people who come from a certain degree of privilege. The working-class voice is just as important, just as entertaining, just as vibrant, just as literary as anyone else’s. So that I think is why she perseveres and hasn’t sunk into obscurity.”

In Holdsworth’s adaptation of Black Teeth and a Brilliant Smile (which, it is worth noting, the surviving members of her family have disavowed), she imagines Dunbar’s answer to the question: “What advice would you give to young working-class writers?” It is characteristically blunt. “Get a proper f***king job. Seriously. Learn to be a bricklayer, work in a shop... you’ll be happier, healthier and you’ll probably be better off. Writing is the hardest thing I’ve done. You see me up here, and you think I’ve made it. But it’s not all it’s cracked up to be. You make money, but then you spend it. Come up with a good idea and they’ll only want you to come up with another and another and another. And then when you haven’t got another decent thought in your head... that’s when they’ll send you back where you came from. Because you’ll always be an outsider to them. A novelty. You see, they think they want to hear the true voice of the north. But they don’t. Because the truth hurts.”

The truth does hurt, but thank goodness Dunbar chose to tell it. “They’ll forget about us by tomorrow,” she once predicted at the height of her success. She was wrong about that.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks