Author Sandra Cisneros explains how writing is a therapy

Veteran writer Sandra Cisneros speaks to Alexandra Tirado Oropeza about her career, independence and making her bed

Sandra Cisneros never thought she’d own a home. Growing up with six brothers and her two parents in an immigrant neighborhood in Chicago, she always dreamt of a place of quiet, where she could be alone, have messy hair and not have to make her bed.

She had dreamt of a land of solitude where her thoughts could be put to paper and her laundry didn’t have to be neatly folded every time. A place where she could be creative, a place where she wasn’t frightened. But never for one moment thought it’d be a house.

As a writer, she was living paycheck to paycheck in her mid-thirties before her book, “The House on Mango Street”, became an international best-seller. It was then that her agent and accountant broke the news to her: you can afford to buy a home now.

“It was beyond my dream, you know? I was scared, and every time I would finish paying the house for one year, I said I hope I can do it again [next year]” Cisneros said.

That house was in San Antonio, Texas, and she did end up paying it full. It was the house where she wrote her short story book “Woman Hollering Creek and Other Stories”, her memoir “A House of My Own”, and many other works.

“You don’t need a husband, but you need an agent, an accountant and a financial planner,” she said with a laugh.

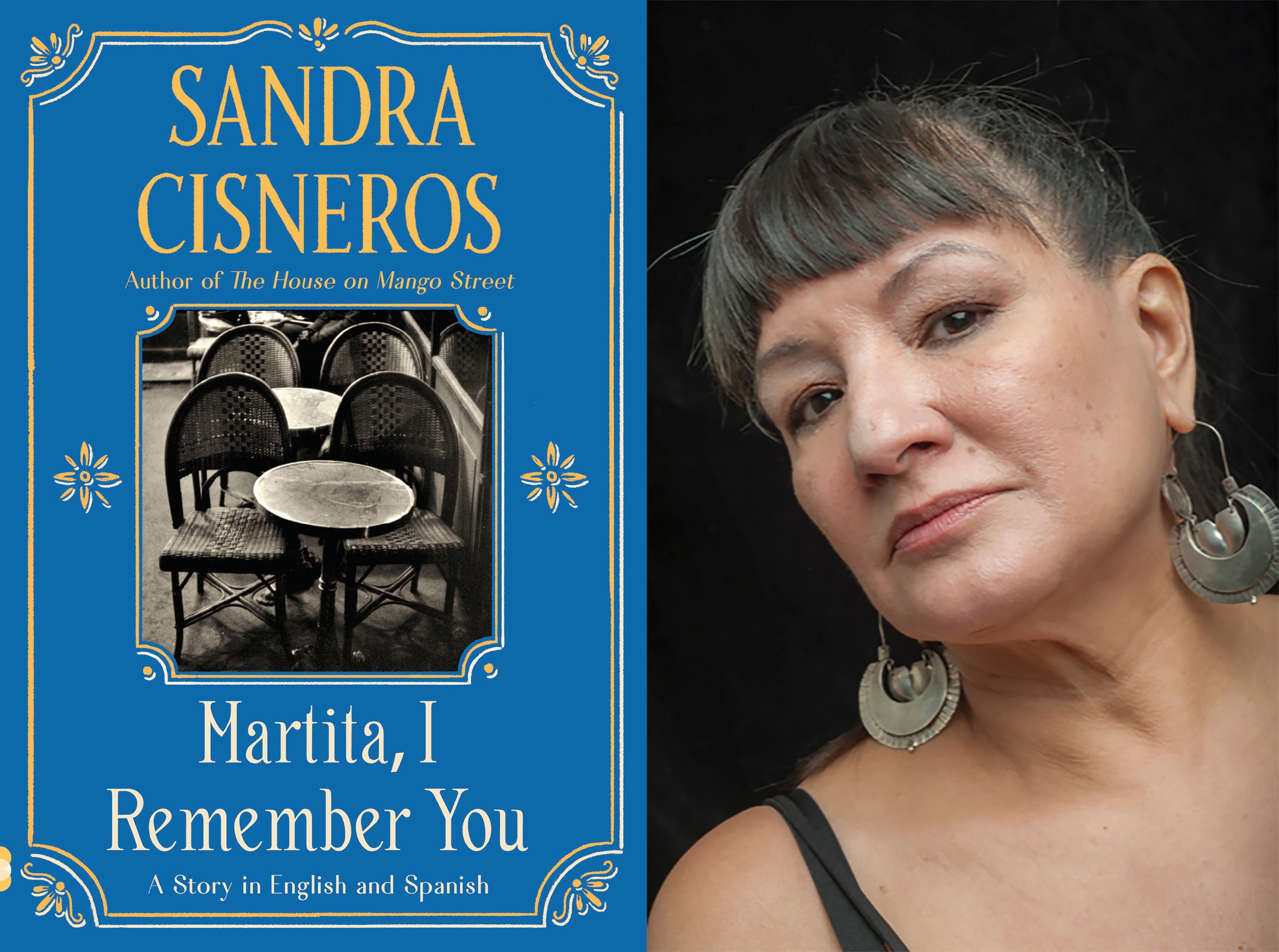

These days, Cisneros lives in San Miguel de Allende in Mexico, in a different house. She just finished a series of press junkets for her latest novel, “Martita, I Remember You/Martita, te recuerdo” and is in the process of adapting “House on Mango Street” into an opera with composer Derek Bermel.

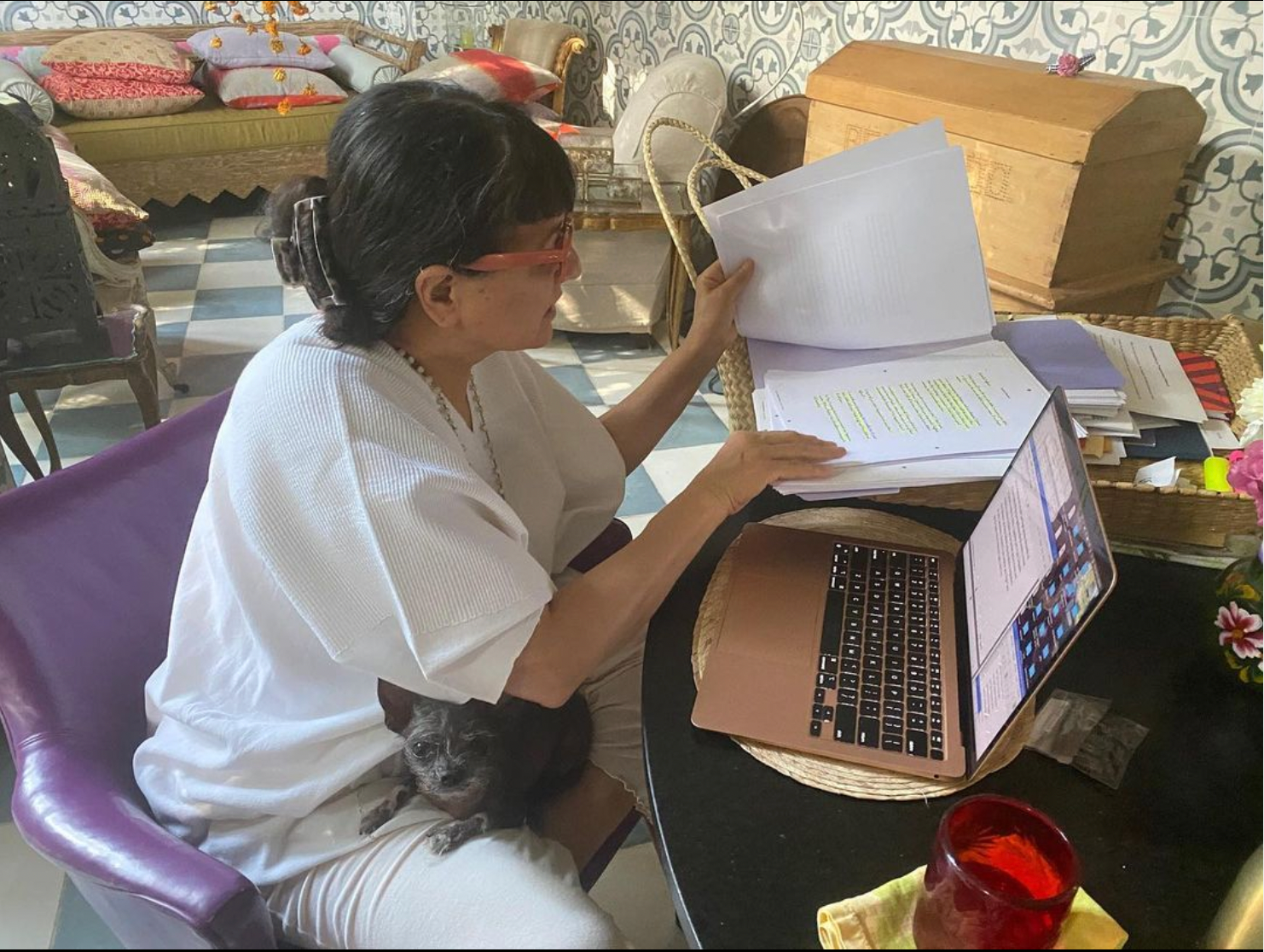

Through our conversation, she is calm and inviting. As we speak, she has her dog Nahui with her, and she is filing her nails as she talks to me from her unkept bed.

“My mother would say, ‘look at you, you didn’t make the bed,’” Cisneros says, smiling. “My mother made the bed every day, but she wasn’t writing – if you’re writing, you don’t have to make the bed, that’s what I say.”

Speaking with Cisneros feels a lot like having a conversation with your favorite tía. She gives advice about maintaining a youthful face (‘writing and facials”), writing (“write what no one writes”) and her three golden rules for young women: earn your own money, cherish solitude and control your fertility.

On the latter, she says, “I have a choice in this lifetime. I’m going to either be alone and raise a child or I’m going to raise books, but I can’t have both.”

There is something that feels irreverent about her because in many ways, the way she’s lived her life contradicts what is often expected of a Latina. In latin culture, there are always certain expectations for women: you should know how to clean, you should know how to cook, and you should have a husband.

But from a young age Cineros had decided she didn’t need to learn how to cook, she wanted to clean only when she felt like it and she didn’t want a husband, either. Instead, she chose to study and become a writer, a decision that was greatly encouraged by her mother, who pushed her to be independent and make her own money.

“My mother was very limited by the opportunities and the generation that she was born in,” Cisneros said. “I think my mom’s life taught me what I didn’t want to be and also gave me the strength to be who I am. Like, I didn’t want to have seven kids with no birth control, you know, eight live births and a couple of miscarriages.”

In life, Cisneros’ mother, Elvira, was a lover of art, always dragging her family to museums and getting all her kids library cards before they could even read. But she was also frustrated with her life, and the fact that she could never become an artist. In death, Cisneros says, she is much happier with her time on Earth.

“That’s beautiful to know that, you know, we can go to our deaths despondent but still develop after we’re dead. So I’m grateful to my mom, especially now in spirit. She has been very supportive and visits me and dreams.”

Cisneros is deeply spiritual, and she believes her loved ones are still with her, even if not physically. But what has really gotten her through her most desperate times is her writing.

“Some people go to therapy, I write,” she says. It was in fact the main reason for wanting to own a house so badly, so that she could write, so she could shut down the noise and discover her feelings through the pen. Anything that takes Cisneros away from writing is almost physically painful.

But for the last decade, her life has been filled with meetings, workshops, speeches, manuscripts, advice, interviews and noise. The woman that cherishes solitude more than most has been put in a position of endless social parade. She calls it being “the ambassador of everything.”

“I felt I had to represent,” she said. “And I think that caused me to do a lot of things that made me stray from my desk; the foundations, the big city gatherings of the writers’ workshops. It’s just, you know, I had to do everything. It was exhausting.”

Certain things are expected after you become a known writer in your community, she says. But is it specifically hard because she is a writer of color?

“I mean, I don’t think writers like John Updike had to be the ambassador for all white men,” Cisneros cheekily points out.

Still, her commitment to the future generations in writing is outstanding. She still leads workshops, she still reads manuscripts and she still writes blurbs for up and coming poets. So when it’s time to read for her own pleasure, she doesn’t have time to read any books that don’t serve her.

“You know, my Uber driver may be coming any moment. Say ‘time to go’,” she says, referring to her own mortality. “So I only want to read like the Latino women, and especially want to read books by the younger Latina writers. I want to read all the Latin American writers I didn’t get because I was reading the men.”

She pulls out the book she’s currently reading (Wild Tongues Can’t Be Tamed), and examines the authors’ page. They are all women writing about their experience in the Latino diaspora, and she is determined to absorb their words. She wants to witness them.

“I’m so glad because there’s like 15 writers, and [I only know] two of them,” she says as she goes through the names. “Every time I pick up an anthology that I know two and I don’t know the rest, that’s a good sign because that means that they can be the ambassadors. And I can be the ambassador of me.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks