Riverdance at 25: How a Eurovision performance sparked an Irish cultural phenomenon

Ben Kelly looks back at six minutes that reinvented Ireland’s traditional dance and its image on the world stage

From ABBA and Celine Dion to Russian grannies and a singing turkey, the Eurovision Song Contest has dazzled, entertained and confused us endlessly over the decades. Twenty-five years ago, it was also the stage that first gave us that most essential Irish cultural phenomenon: Riverdance.

In 1994, Ireland was preparing to host Eurovision for a second year running. After inviting Europe to the tiny Cork village of Millstreet for a rural affair in 1993, this time around RTE were bringing things back to Dublin.

Executive producer Moya Doherty was in charge of overseeing the broadcast. In an attempt to modernise the show, Doherty introduced the practice of countries delivering their votes on camera via satellite link. But her pièce de resistance was the interval act.

“I decided early on I wanted dance – we’d have singing all night,” she explains. “Irish dancing is our tradition. People start at the age of four, it’s very much part of our past. This performance was born out of a particular moment in Ireland’s cultural development.”

The Point Theatre venue sits on the city’s docks, at the gateway from the River Liffey to the Irish Sea, and Doherty exploited this geographically to find a theme for the entire show.

“The Liffey was my jumping-off point, so everything we used that night fed itself out of the flow of the river. I wanted to create something that reached back, that touched the face of our grandparents, but also had a hand reaching forward as well.”

Doherty brought together composer Bill Whelan and the Irish-American dancers Michael Flatley and Jean Butler, who were at that point bringing a new energy and athleticism to Irish dance in their own work. The piece they built from scratch would bridge that gap between the traditional and the modern.

Breandan de Gallaí was one of the dancers picked for the performance. “It was a big, top secret thing,” he says. “I was picked initially with the dance captains and choreographers, and then they did a wider audition to get the rest of the company.

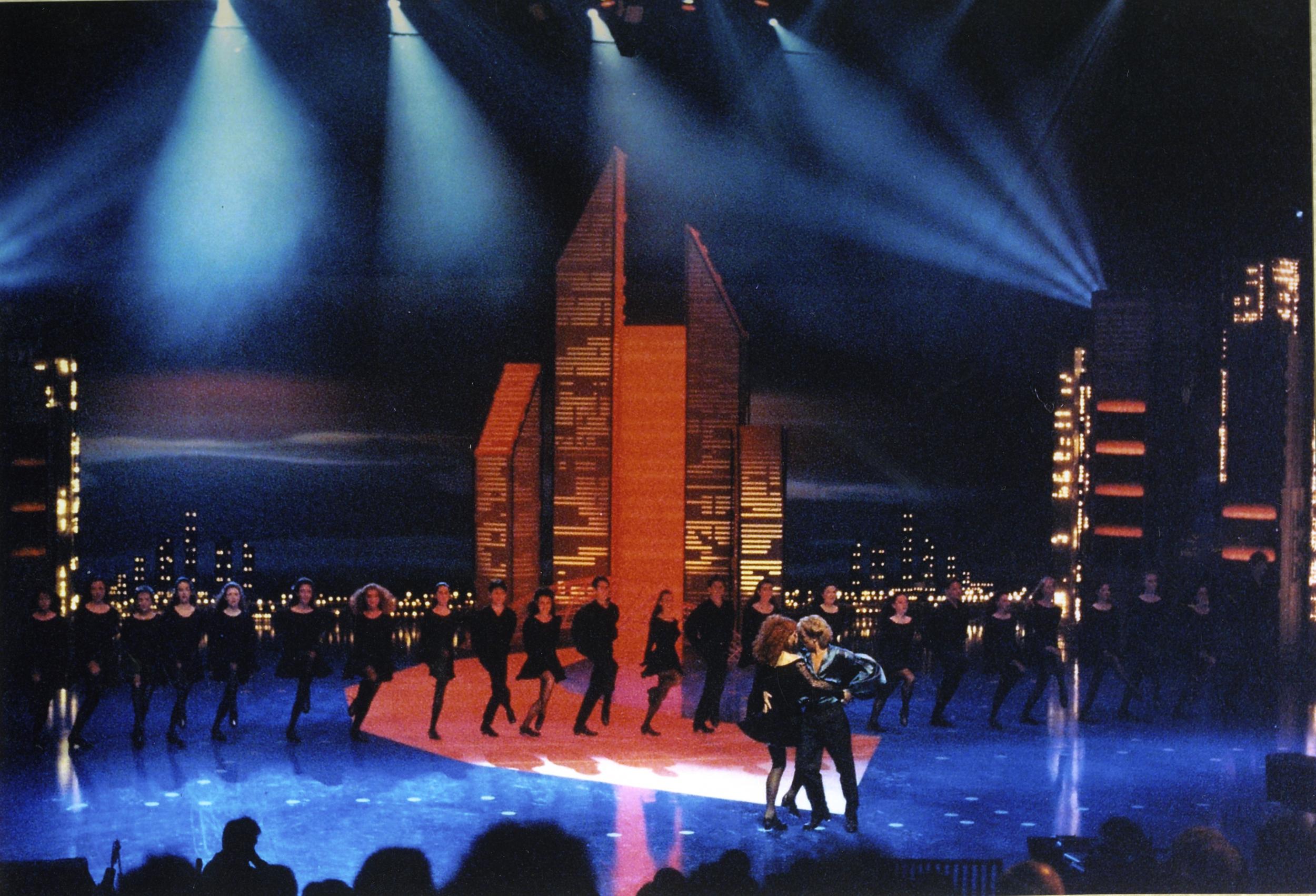

“Irish dancing was traditionally performed as a solo thing in competitions, or in small groups for tourists. What was different here was the scale of what we were doing, the audience we were broadcasting to, the context of how it was all tarted up with the lighting and the set.”

Those who had seen rehearsals or been played clips of the music passed on rave word-of-mouth reports to others, and the much-anticipated performance became all the talk around RTE. “We knew it was significant,” says De Gallaí. “We had a feeling that this reaction was coming.”

The big night came on 30 April 1994. After 25 countries had performed their songs, with an audience of millions watching across the continent, Riverdance was unveiled. The performance began with singing from the Celtic choir Anúna, setting a haunting, mystical atmosphere, before Jean Butler emerged from a traditional Irish cloak to perform a solo soft-shoe dance.

But the arena was stunned when a battering of bodhráns heralded the arrival of Michael Flatley – a man whose footwork is now so legendary and much-parodied, it’s hard to imagine seeing it for the first time.

Tapping his way across the stage, Flatley immediately turned Irish dancing on its head, exchanging sombre clothing for a satin blue shirt, and keeping his arms not rigidly locked to his sides, but releasing them expressively and ostentatiously.

Gone were the style’s old folksy associations, as Flatley delivered dynamism and showmanship, referencing styles as diverse as the tap of Fred Astaire and the sexiness of flamenco.

The pair were then joined on stage by a whole troupe of Irish dancers, who flowed out into a Broadway chorus-style line to deliver the rousing finale, in which a full-bodied orchestra battled with the clatter of tap shoes. A moment of cultural history was made.

The roar from the audience at the end was practically tribal, more like the noise at a football match than your average response to a piece of dance. “Good grief!” Terry Wogan cried to his BBC audience. “Small hairs rising on the back of every Irishman’s neck.”

Eurovision superfan Daniel Pashley was one of the hundreds of people in the audience for that unforgettable moment. “I’ve never seen anything like it,” he says. “The audience was just captivated. And then, when it finished, the reaction was incredible. My friend just looked at me – we knew we had just seen something pretty special.”

An RTE cameraman captured the moment when Irish president Mary Robinson wiped a tear from her eye, and regrets not broadcasting what he thought was a “cheap shot”.

The Eurovision set, with its nocturnal cityscape, placed Riverdance in a thoroughly modern context. This was a demonstration of Ireland’s new-found national confidence, which wasn’t entirely removed from the Celtic Tiger (the economic boom enjoyed in the 1990s). It propelled the island nation’s modest culture onto a larger European stage. In just over six minutes, Riverdance had reimagined what people thought about Ireland.

That night, Ireland also won the competition for an historic third time in a row – for the wistful ballad “Rock’n’Roll Kids” – but this feat was almost glossed over. All anyone could talk about was Riverdance.

Almost immediately, people contacted RTE asking where they could buy a tape of the performance or a ticket to the live show. But none of this had been anticipated. Straightaway, plans went into action to create a full-length Riverdance spectacle, which eventually premiered in 1995.

It has since played in hundreds of venues around the world, witnessed by over 25 million people, with special performances for queens, presidents and popes. It became one of the biggest cultural phenomena in the world, and certainly one of Ireland’s most successful exports ever.

“I think it really needed that European dimension to deliver the impact it deserved,” reflects Moya Doherty. “If it launched only in Ireland, it might not have. It encouraged a willingness for Ireland to look at itself from an international perspective – to tell our story in a way that outsiders, nearly 600 million people, would comprehend.”

It’s from this unique inception that Doherty believes Riverdance drew its longevity, too. “It has survived because it was built on something which is imprinted on the hearts and souls of all Irish people and the diaspora around the world. It was our culture being celebrated as an art form.”

Today, she marvels at seeing dancers from as far afield as Canada, Australia and Japan getting involved in Irish dancing, despite the fact that some of the young performers on tour don’t even have Irish heritage. This phenomenon is a testament to the influence of “soft power”, she argues, and sharing the traditions of other nations.

“It gives me tremendous joy to see us reach across borders through culture,” says Doherty. “In the times we live in now, I’m kind of proud of the message of Riverdance.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks