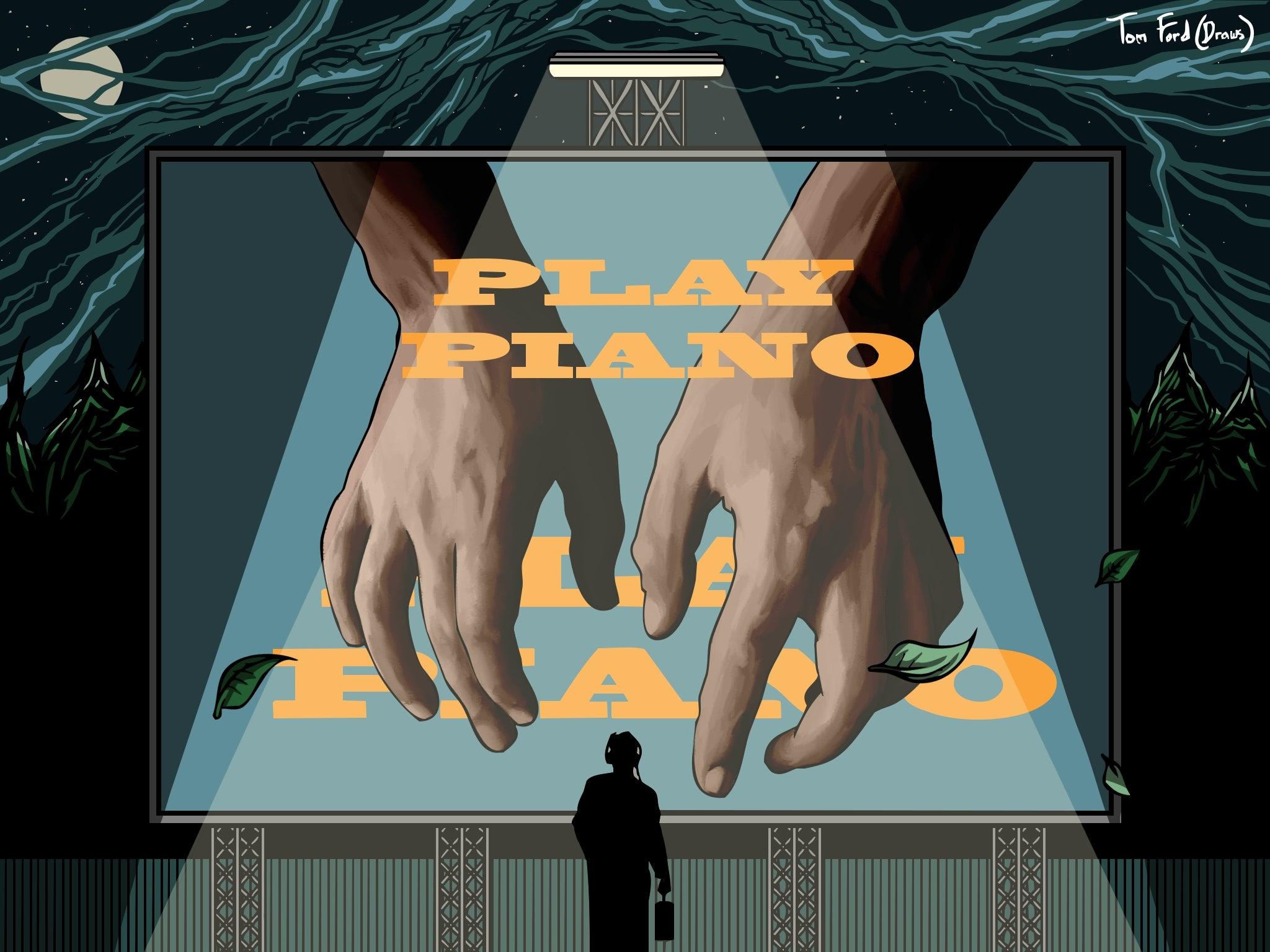

An intense relationship with the piano

The Outsiders: Continuing his series, comedian Dan Antopolski tells us why learning an instrument is a human birthright – even if you hammer the keys

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.I wrote recently in this place about my love for synthesisers, but of course behind every charismatic electronic keyboard player whom all desire – ranked in magnetism beneath only the singer, guitarist, drummer, bassist, saxophonist and Bez – there is a pianist, whose parents had a piano and who was likely made to play it from a young age, his legs dangling from the stool.

Music tends to run in families – mine came from my mother’s side. My maternal grandfather was a lifelong violinist – indeed he died, by asthma attack, after insisting on braving the snow to play with his quartet. I hope I go the same way – insisting on something.

His son, my uncle, told me that he had never progressed as a musician because my grandfather had tried to inculcate in his children a love of instrumental practice, rather than a love of music. I credit my mother with this evolution: she understood the role of voluntary play in learning and endured me playing chopsticks for 10,000 hours. By the end of all that diddle-um dum dum, my fingers were at home on the keys.

She played the piano too and when we were small she would play and sing folk songs and ballads from the American songbook – work songs, African American spirituals and stirring union anthems – anything with what she called “a bit of oomph”. We sang as a family in a good and naive way that would cause my children’s heads to explode with embarrassment if I ever tried to introduce it in one of my faddish, daddish enthusiasms for perfecting family life.

Nevertheless, that love of melody – and the idea that music is all of ours to make, as well as consume, was planted in my infant mind. I own music.

I had some good teachers too. One was Judy, a very nice hippyish lady in Highgate, north London – you don’t get them so much any more but there used to be lots of them, they wore layers of wool and had cats and Indian prints everywhere and so forth. Judy used to draw a jaunty pair of glasses with directional eyeballs to focus my attention on bits of the week’s piece that needed work. Her lessons always ran late and she would still be teaching the previous pupil when I arrived so I would hang out in a book-filled room and leaf through what I found there, mainly Robert Crumb comics – which blew my mind and which I should not have been reading at that age.

Judy had a lodger called Tom. He had a gammy arm and my mum called him dapper. I thought I understood what a lodger was but he and Judy seemed to be intimate. I frowned once at the effort of trying to comprehend their relationship and Judy caught my confusion and said that surely it was normal to have a lodger – someone to share a cup of tea and cuddles. Well, that was as clear as mud – tea yes, but cuddles? It was the Seventies and Thatcher had not yet ruined tea and cuddles – I don’t know why I was being such a massive square about it.

I don’t play so often now but over my brooding teen years, I had an intense relationship with the piano. I used to come home from school and regularly bang away at it for an hour, two hours. My mother would complain that my playing was too hard, which ostensibly meant it lacked dynamic range but really meant that she was triggered by my aggression.

I don’t play so often now but over my brooding teen years I had an intense relationship with the piano

For my part, I had begun to find her playing controlled and arch; her fingernails clacked on the keys – theatrically I felt, to imply great sensitivity – and her rallentandi were melodramatic. So we waged a subtle and necessary war of gender and generation through the media of her wilfully chétif mezzo-forte and my truculent sforzandi which shook the walls. We were a great family. Later when I watched Wes Anderson’s The Royal Tenenbaums, I laughed much harder than anyone else in the cinema, disquieting my companions.

It is true that I used to hammer the keys – especially the left hand, making each note do the work of the drums in grounding and framing the rhythm so that the right hand could syncopate freely and meaningfully. Even now my left thuds down like Mjolnir. When I was in bands, it was an effort to cede to bass and drums that part of the frequency spectrum which was rightfully theirs.

In 2003 in Melbourne, Australia I was unwinding after my stand-up show, drunk and playing the piano in a great bar. I was improvising really well for some reason, my phrasing was effortlessly lyrical – jet lag maybe. Another drunk man lingered near me and said it was the best music he had ever heard. I drunkenly thanked him, but his praise broke my relaxed focus and my playing became derivative. He grew irritable and told me to stop playing “that shit” and carry on with the good stuff. I told him I didn’t know how I was doing it. We started chatting and with my monkey brain distracted, the playing got good again, until I noticed, screwed up and earned again his swaying ire.

I make my kids learn the piano and I hope that the feeling of ownership and expression in music takes root in them, because it’s a human birthright. And also you, reader: even if you are at work in your office cubicle, adjoining a corridor patrolled by a humourless overseer, do this for me. Tap a rhythm on your knees and sing a song you like, albeit quietly. I give you permission.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments