Three of the earliest 'photographs' ever taken

Little-known photography pioneer Joseph Nicéphore Niépce's 'heliographs' go on display in Bradford

.JPG)

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.A trio of rare images “dating back to the genesis of photography” by the world’s first photographer are going on show 250 years after his birth.

The images by Frenchman Joseph Nicéphore Niépce (7 March 1765 - 5 July 1833), who worked with the better-known Louis Daguerre, were taken in the 1820s.

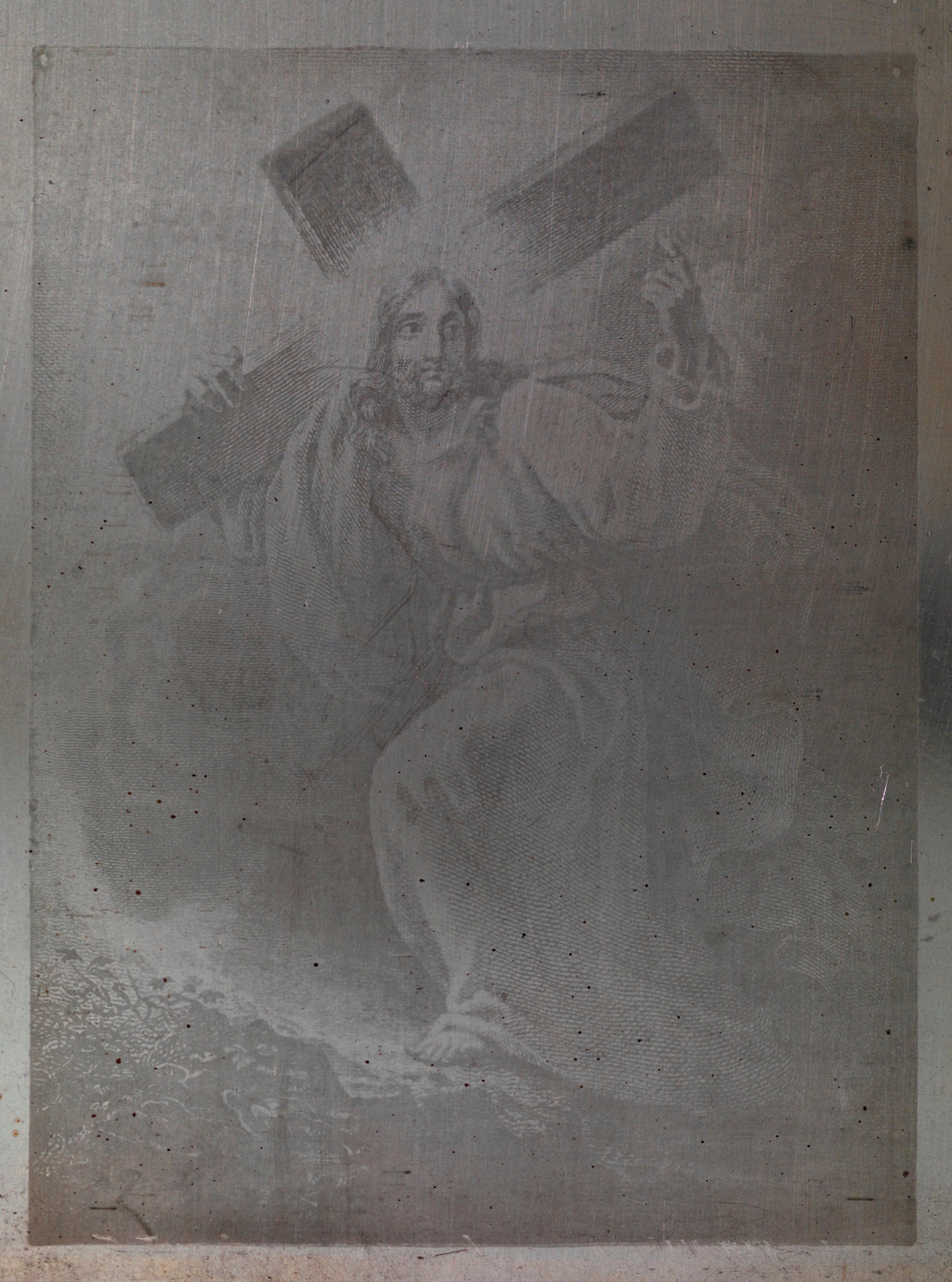

Niépce called his images “heliographs” from the Greek helios meaning “drawing with the sun”. The examples include an image of Christ carrying the cross, a portrait of Le Cardinal d'Amboise and pastoral scene (above) which appears to be a graveyard.

There are only a dozen such early photographs in the world according to Colin Harding, curator of the National Media Museum where the photos will be exhibited. He says having three together in the same place is “extremely rare”.

“Niépce brought six photographs across from France to England because he wanted to present them to the King George IV and Royal Society but the meeting never happened,” Harding told The Independent. “He went back to France but left three of them here.”

Harding says the images go back “to the genesis of photography” and predate Niépce’s partnership with Daguerre (father of the Daguerreotype) whose work would overshadow his own.

“The idea was to create a substitute for hand engraving that could be replicated, like a printing plate,” Harding says. The process uses a kind of asphalt and lithography on pewter which when exposed to light in a camera obscura makes the image hard and insoluble.

“These images are not made from nature,” Harding says. “They are made from exposing objects, hand drawn engravings. But because they are made using light they are technically the earliest known photographs.”

Niépce, who also invented the world’s first internal combustion engine, is credited with taking the earliest known surviving ‘photograph' - a view from a window of his house in Chalons-sur-Saône, which required an exposure of about 8 hours.

Niépce received no posthumous credit for the daguerreotype process which he worked on with Daguerre from 1929 onwards. He died of a heart attack, aged 69 in 1833, six years before daguerreotypes were announced to fanfare in 1939 and became the most popular form of nascent photography for 20 years.

Only 16 heliographic plates by Niépce are known to be still in existence with the three going on display having been presented to the Royal Photographic Society in 1924 by the son of eminent photographer Henry Peach Robinson who had acquired them for his private collection.

The discovery of Niépce’s heliography process re-wrote photography history when it was established by the Getty Conservation Institute and the National Media Museum in 2010.

The images go on display from 20 March at the Bradford-based museum as part of a wider exhibition of highlights from the Royal Photographic Collection.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments