Scholar by day, street-sweeper by night, one black man navigates Rio’s racial divide

Labourer and father Felipe Luther is making his mark on an elite Brazil university

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Felipe Luther spends his afternoons studying for a degree from one of Brazil’s top universities, tucked in the green hills of Rio de Janeiro above the ritzy beaches of Leblon and Ipanema.

He spends his nights in those wealthy communities sweeping the streets.

“When I tell my classmates about my job, they’re often shocked,” Felipe says.

In 2017, he got a full scholarship to the social sciences programme at the Pontifical Catholic University of Rio (PUC-Rio), a private school that has minted central bank presidents and film stars.

Felipe’s rare opportunity and daily routine are reminders of the disparities in Brazilian society and Rio in particular, where fresh debate about the dangers and disadvantages facing black men like him was stirred in May after police killed dozens in a raid.

Felipe, 38, had passed up college for work to support his family, including a job sweeping streets since 2009.

“Many students like me start working when they are very young,” says Felipe, who comes from humble roots in the northern reaches of Rio, more than two hours from the campus.

“This reduces the time and structure they need to be able to compete with children of the elite,” he adds.

Studying at PUC-Rio has put Felipe’s dreams within reach, while bringing him face-to-face with the overwhelmingly white elite of a country where 54 per cent of people have African ancestry.

In 2000, the national census found white Brazilians were five times more likely to have attended university than their black, mixed-race and indigenous peers.

“Because there are so few black people at this renowned university, many view black folks as servers, not as fellow classmates,” Felipe says, recalling awkward run-ins on the campus.

In one case, a woman mistook Felipe for an elevator operator. In another, someone tried to pay him for a cup of coffee, confusing him with cafeteria staff.

“It hurts, in a way, because you get the impression that you don’t belong there,” he reflects.

Brazil’s educational inequalities have only grown during the pandemic, as remote classes force students to rely on resources at home, widening a gap between the haves and the have-nots.

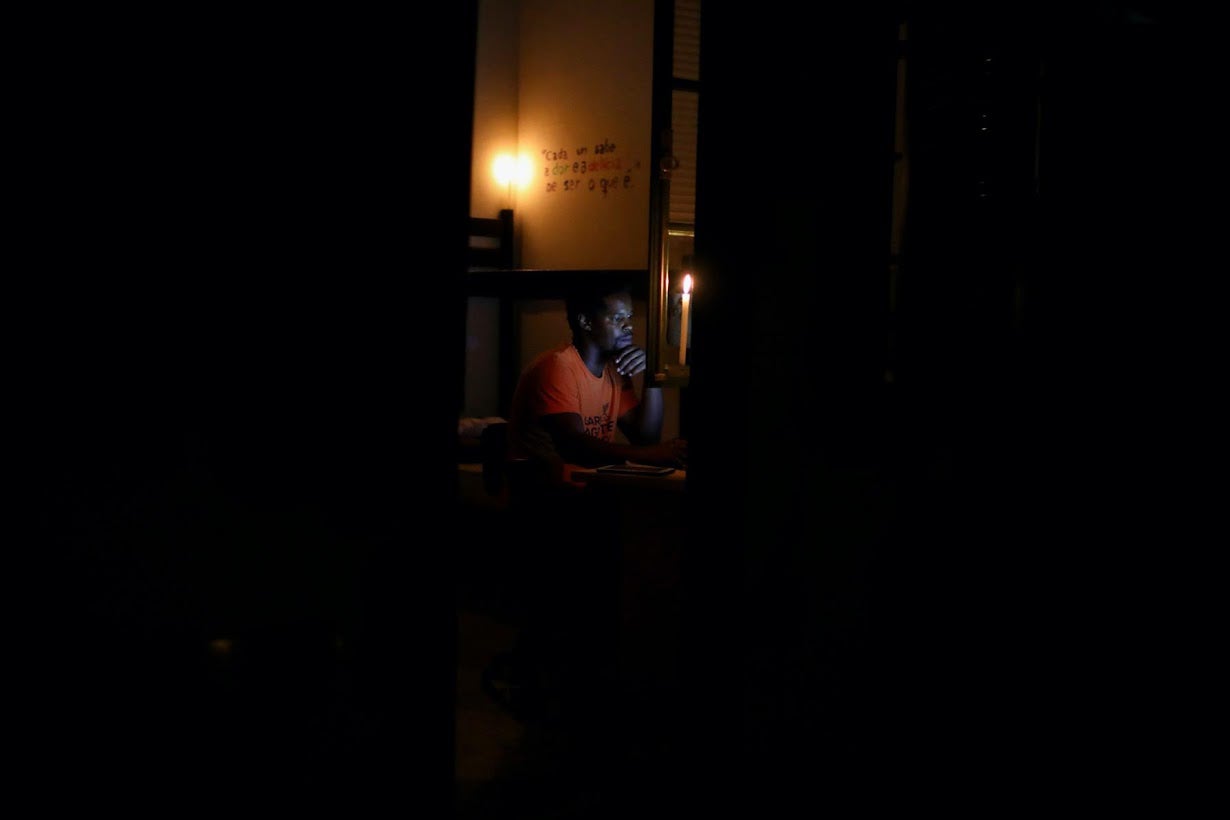

For months, Felipe was reading at night by candlelight in Niteroi, across the bay from the campus, where his student residence often lacked power. He charged his phone and laptop at work and used them to study until his street-sweeping shift from 9pm to 5am.

“For my course, which demands a lot of reading, I need a better computer than the one I got but some people aren’t even given a computer,” he says, noting the array of challenges for disadvantaged students forced to study from home.

“Not all phones are good enough for working and not everyone has a phone or enough internet data to download their readings.”

Recent events in Rio have underscored even greater challenges Felipe faces.

In May, police stormed Jacarezinho, a poor community in northern Rio, in a raid targeting the Red Command drug gang. The hours-long shootout killed 27 men in the neighbourhood and one officer, making it one of the deadliest police operations in the city’s history and drawing backlash from human rights groups.

Felipe, who has two sisters living a few minutes from Jacarezinho, joined a demonstration in Rio the week after the deadly raid, using the official anniversary of abolition in the country to protest against police violence against Afro-Brazilians.

“NO to genocide against black people,” read one protestor’s sign.

Felipe says he lives in constant fear of police violence and makes a point of staying off the streets in certain neighbourhoods at night.

“Even if I were rich or very famous, I would still be living in a black body in a city, a state, a country where black people seem expendable,” he says.

More than three-quarters of the almost 9,000 people killed by police here over the past decade were black men, according to Human Rights Watch.

Despite threats, Afro-Brazilian culture continues to thrive as it has for centuries.

Twice a week, Felipe visits a local terreiro to practice Umbanda, a religion with origins in West African spiritual traditions. Dressed in all-white clothing with beaded necklaces hanging over his chest, Felipe participates in dances, songs and rituals with fellow believers.

“It connects me with my ancestry,” he says.

Popularised in Rio in the 1930s, Umbanda, like fellow Afro-Brazilian religion Candomble, has roots in the transatlantic slave trade, which brought as many as five million enslaved people from Africa.

Those who sought to practice their rituals free from the harassment by Europeans would blend their native traditions with elements of Catholicism, creating syncretic religions now practised by over half a million people in the country.

Churches often serve as community centres, like the one where Felipe took a free college prep course in 2017, setting him on his journey to PUC-Rio.

Once he gets his degree, Felipe says one of his goals is to begin teaching college prep courses in low-income communities, opening the door for the next generation of aspiring students.

“I want to give back to other young people by allowing them to hope that this is possible,” he says.

Reuters, photography by Pilar Olivares

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments