From the inside: How Tish Murtha’s images of people on the margins of society challenged inequality

Murtha was from the same streets as the community she photographed, lending a poignant intimacy to her stark yet tender black and white photos

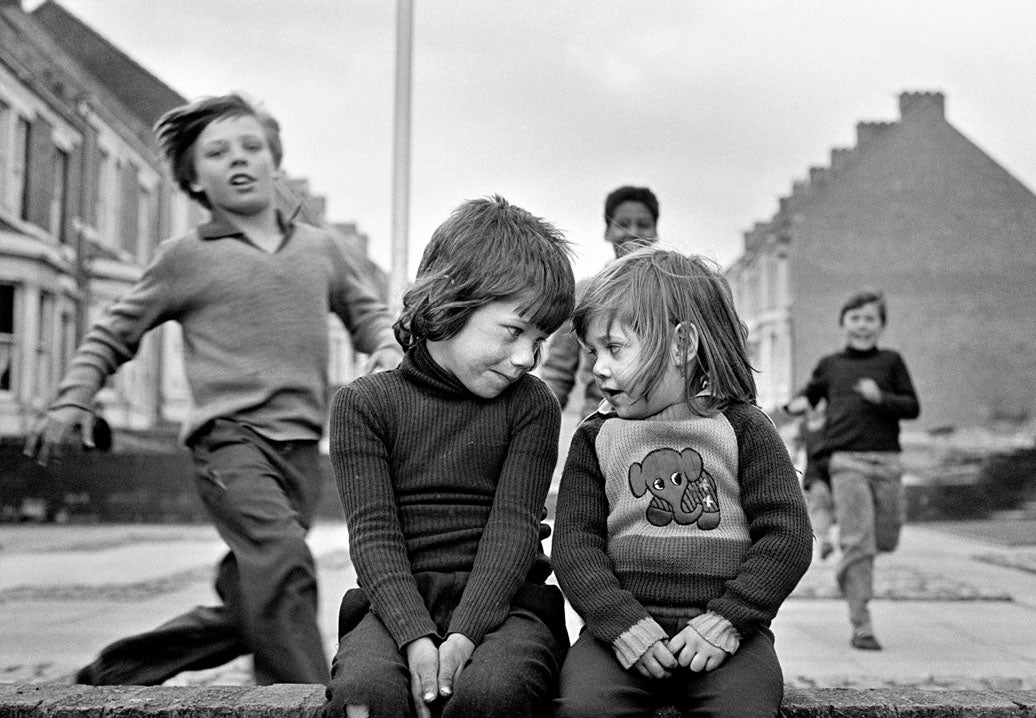

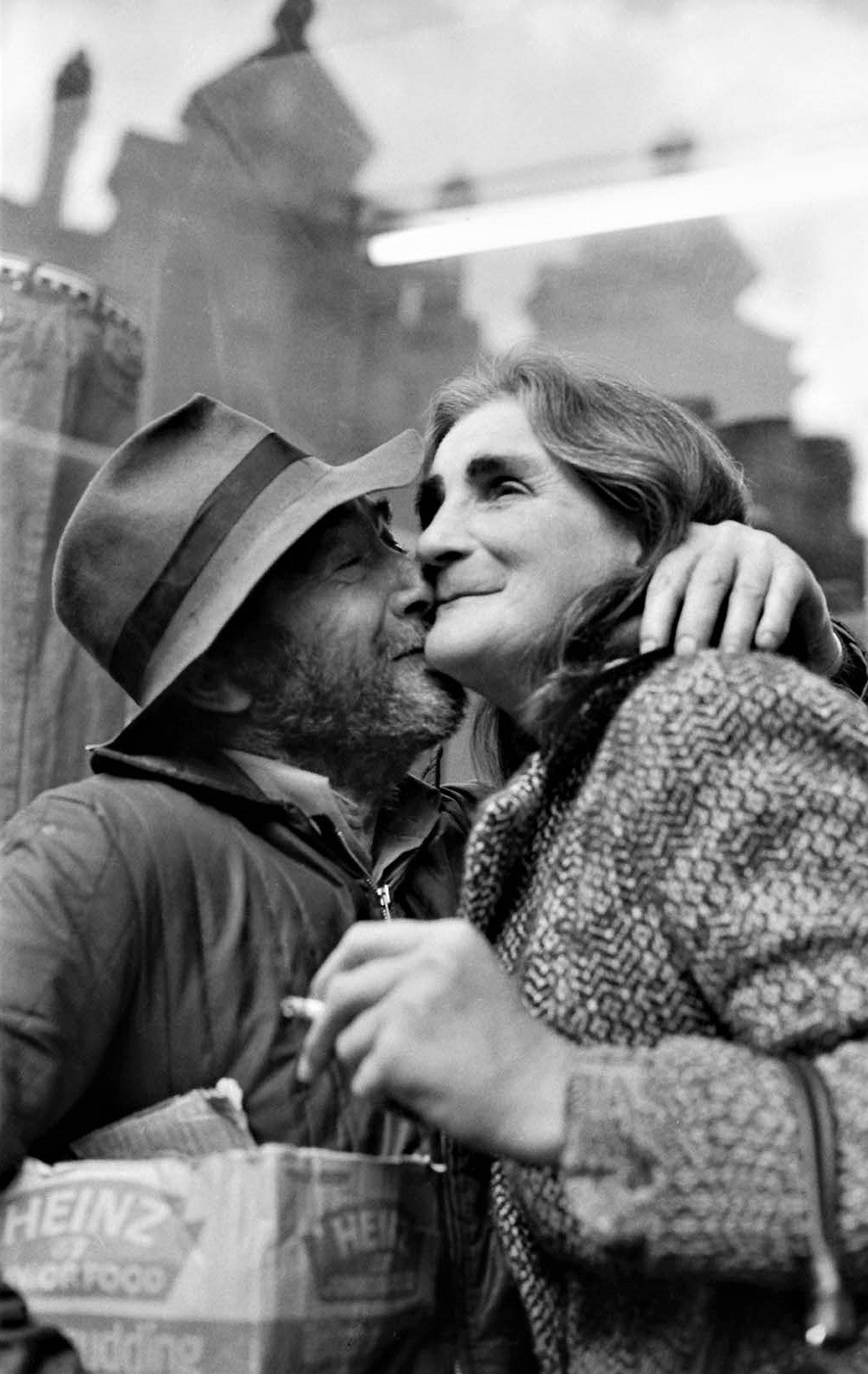

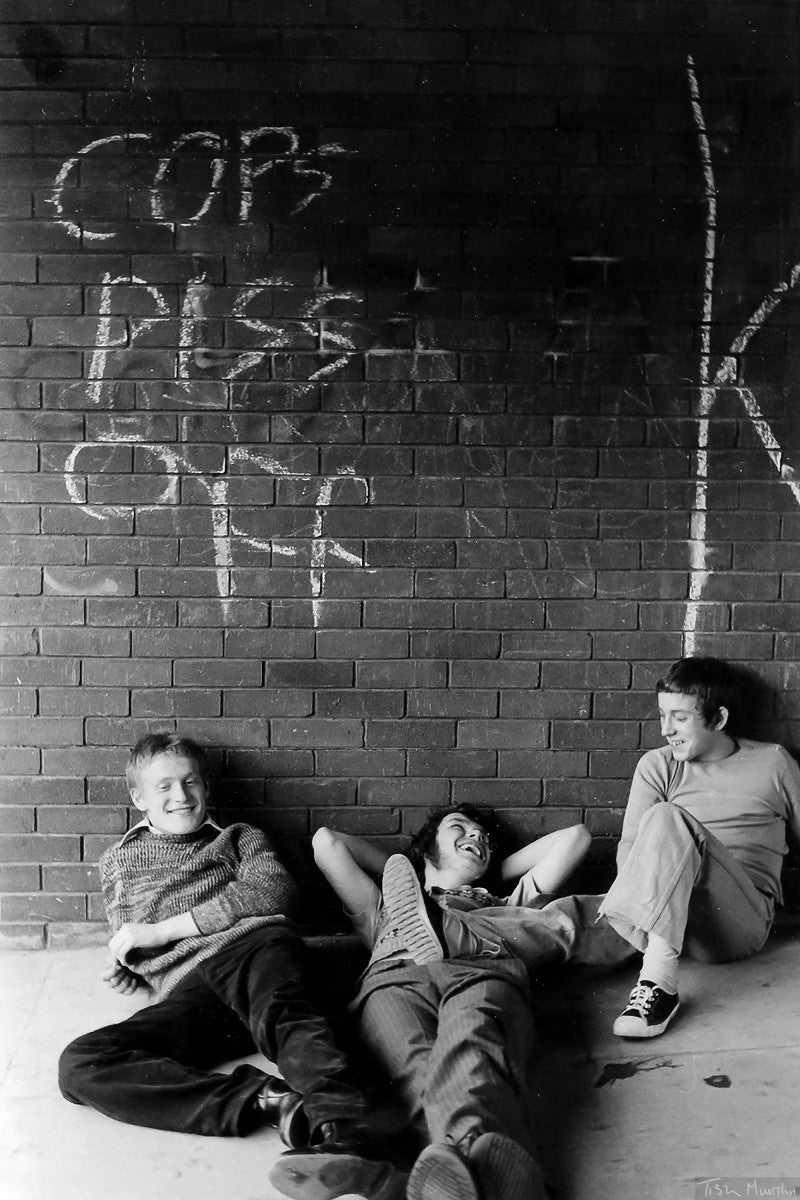

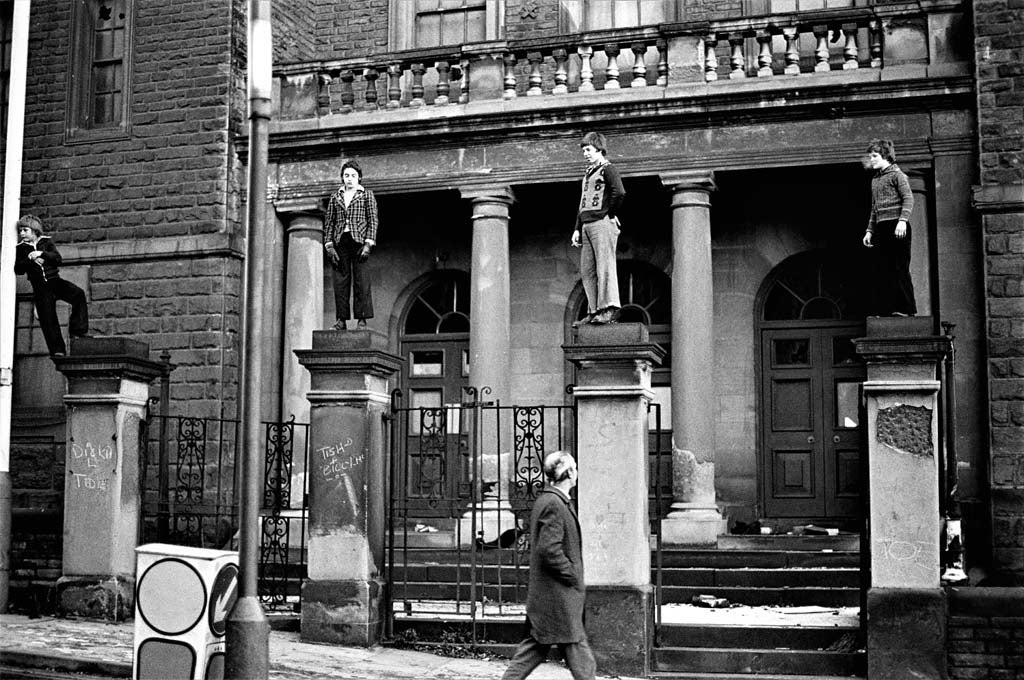

People are always at the centre of Tish Murtha’s photographs. Through her eyes her hometown of Elswick, a working-class neighbourhood in Newcastle, looks like a film set of some war-torn city. But she began shooting in the late 1970s, far from wartime – the flat vistas of burned cars and destroyed houses are the result of neglect, deindustrialisation, and poverty. It’s the contrast between the bleak landscape and the intense vitality of the people amongst the rubble that makes her work extraordinary.

One of ten children brought up in a local council house, and enrolled on a youth unemployment scheme herself, Murtha was one of the rare photographers to document life in marginalised communities from the inside. Her first two exhibitions focused on the lives of young people in the area, often friends and family. The pictures capture her subject’s defiance, warmth and a sense of community at odds with the dire circumstances they were born into. She was especially adept at spotting moments of tenderness and quietness amid the chaos of the housing estates; her work is infused with a humanity that makes it timeless.

Filmmaker Paul Sng, who grew up on a council estate in southeast London, was enthralled by Murtha’s work from the beginning. “The first photo I saw was ‘Kids Jumping onto Mattress’,” he says. “I was captivated, there’s so much going on. For me, it speaks to the ingenuity of working-class communities back then… We got up to all sorts of mischief and often it was quite perilous, but it was great fun. Tish captures all of these elements in that one image. It speaks to the period but retains an urgency that makes it seem fresh to my eyes each time I look at it.”

Her work was explicitly political. In an essay accompanying her 1981 exhibitionYouth Unemployment at Newcastle’s Side Gallery, Murtha expressed deep concern over the lack of opportunities available to the people in Elswick after the mass closures of local mines and factories. “There are barbaric and reactionary forces in our society, who will not be slow to make political capital from an embittered youth,” she wrote. “Unemployed, bored, embittered and angry young men and women are fuel for the fire.” The essay was read out in the House of Commons in 1981 by Robert Brown, then the MP for Newcastle upon Tyne North – a testament to the power of her work.

After moving to London in 1982 she worked with legendary photographer Bill Brandt on a series London By Night, documenting the lives of Soho sex workers with her characteristic energy and empathy. It seemed like the beginnings of a singular career, a vital new voice in British photography.

Read more:

Then, Murtha became pregnant with her daughter Ella. The art world had no support system – or much interest – in continuing to develop the talent of a single mother, and eventually, she returned to the northeast. Although she continued working, she never published a photobook in her lifetime, and never had another exhibition. She died suddenly of a brain aneurysm in 2013, aged 56.

Although her career effectively ended at Ella’s birth, it is now Ella who is pushing to have her mother’s work celebrated in the way it always should have been. After starting the Tish Murtha Archive, she published a series of photobooks including the Youth Unemployment series. Now she has paired up with Sng, a director who recently released his celebrated documentary, I Am A Cliché, about the outsider punk musician Poly Styrene. Their Kickstarter-funded film TISH will focus on Murtha’s work and life, much of which remains obscure.

“Tish Murtha was an outsider; she didn’t fit into boxes and she did things the way she thought was right,” says Sng. “She didn’t suck up to people in order to progress in her career or do things to compromise the integrity of her work.”

“Like so many working-class artists, Tish was failed by a system that often ignores, misrepresents and marginalises working-class lives and stories. Tish should have been championed and supported by arts funders and photography galleries; they should have bent over backwards to elevate her and her work.”

“Ella told me that she was seen by some in the photography world as an ‘angry woman’, which they used to justify the lack of support for her. The idea that this principled, working-class woman could be dismissed so reductively shows how class snobbery and misogyny contributed to why she was neglected as an artist.”

Ella Murtha believes her mother’s work has as much power now as it ever did. “We are living through incredibly divided times, where working-class people have been manipulated, just like the class warfare that my mam warned about in the essay for her exhibition Youth Unemployment,” she says. “There has never been a more relevant time to go back, meet the people from these photos and really try to understand how their generation were exploited and devalued.”

Sng believes that Murtha’s work is an important part of British photographic history. “Her vision and framing are indisputably brilliant, but it’s her empathy for her subjects and her politics I connect with most,” says Sng. “To me, she’s as important – and as vital – as Asif Kapadia, Patrick Keiller, Lynne Ramsay, Wong Kar-wai or any of the filmmakers whose work has moved and motivated me.”

The film is ambitious – Sng and Ella Murtha hope to recreate the old council flat from the early 1980s, shared with her mother, which will include a lounge and darkroom. “There’s no video footage of Tish, so we need something that can show the audience how she lived and worked,” says Sng.

“It’s important to tell the story of a working-class female photographer and explain why she was never able to fully escape the poverty she grew up in,” says Sng. “Not through being lazy, feckless or ‘unlucky’, but due to systemic inequality.”

Donate to the Kickstarter for the documentary TISH here. It is accepting donations until 1 April

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks