In photos: Risking it all – for the sake of humanity in 2022

Humanitarian photojournalist Paddy Dowling reflects on a decade of work covering crises across the globe, and the enormous sacrifices of photojournalists to promote a more equitable world

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In an increasingly complex geopolitical landscape the world needs courageous storytellers. However, telling the truth has its costs; and this can be your life.

Photojournalists trapped behind the lens, and more painfully, in front of their subjects, are prepared to pay the ultimate price to capture the truths encapsulated in a handful of frames and stories. But do the rewards warrant the risk and does photojournalism change people’s attitudes?

Exactly two years ago I published an article “The most marginalised children across the world. What hope is there for them in 2020?” This reflected on – what then seemed a thankless task – of holding those responsible for their failed promises to the children of the world.

No sooner had I submitted that piece to my editors I was on assignment flying to Lebanon to document Syrian refugees displaced by civil war. They were facing their ninth winter perched high up in the snow-capped mountains of Arsal – once an Isis stronghold. I found refugees huddled together in their tents, living in freezing conditions – as low as -8C by night – and burning what they could find to keep their stoves lit, even old shoes.

I discovered two children, aged two and five. They had not eaten for three days. Their father Nayef, a former law student, explained “nobody comes here to help us any more. The whole world has washed their hands of us, how can I care for my children?”

The world had grown tired of the Syrian crisis. Why?

With a tight turnaround, I was soon walking the polished marbled floors of connecting airports heading to Darfur, Sudan, to document those orphaned by genocide in 2003.

I sat at the departure gate looking out through the expanse of glass watching aircraft arrive and push-back. I remember thinking to myself for the thousandth time in my career “what on earth am I actually doing to myself, my family, and my friends?” But this time was different.

With my shoulders slumped forward, now staring at the floor, I wiped away the tears as they rolled down my cheek. I started to feel the cracks I had papered over for so long, and which were the results of pursuing a change in humanity, beginning to open. I had now assumed the posture of those beautiful but marginalised people I had the privilege of photographing all around the world – defeated.

The visceral brutality of Darfur’s genocide offered no respite. An estimated 300,000 people were massacred by Janjaweed rebels. They had answered a call-to-arms by the former president, Omar al-Bashir, to orchestrate the ethnic cleansing of tribal minorities.

Ibrahim explained his last memories of his father were when rebels arrived in cars and pick-ups with rear mounted guns and opened fire on men women and children. They spilled through the village on foot and killed, raped, looted and burned. He witnessed his father murdered.

The people of Darfur had long been forgotten by the world. Why?

By March 2020 we were all grounded because of the coronavirus pandemic, oblivious of what was about to unfold. As the days, weeks and months disappeared I stared at my canvas camera bags, desperate to be away trying to change the world for the better – doing what I loved.

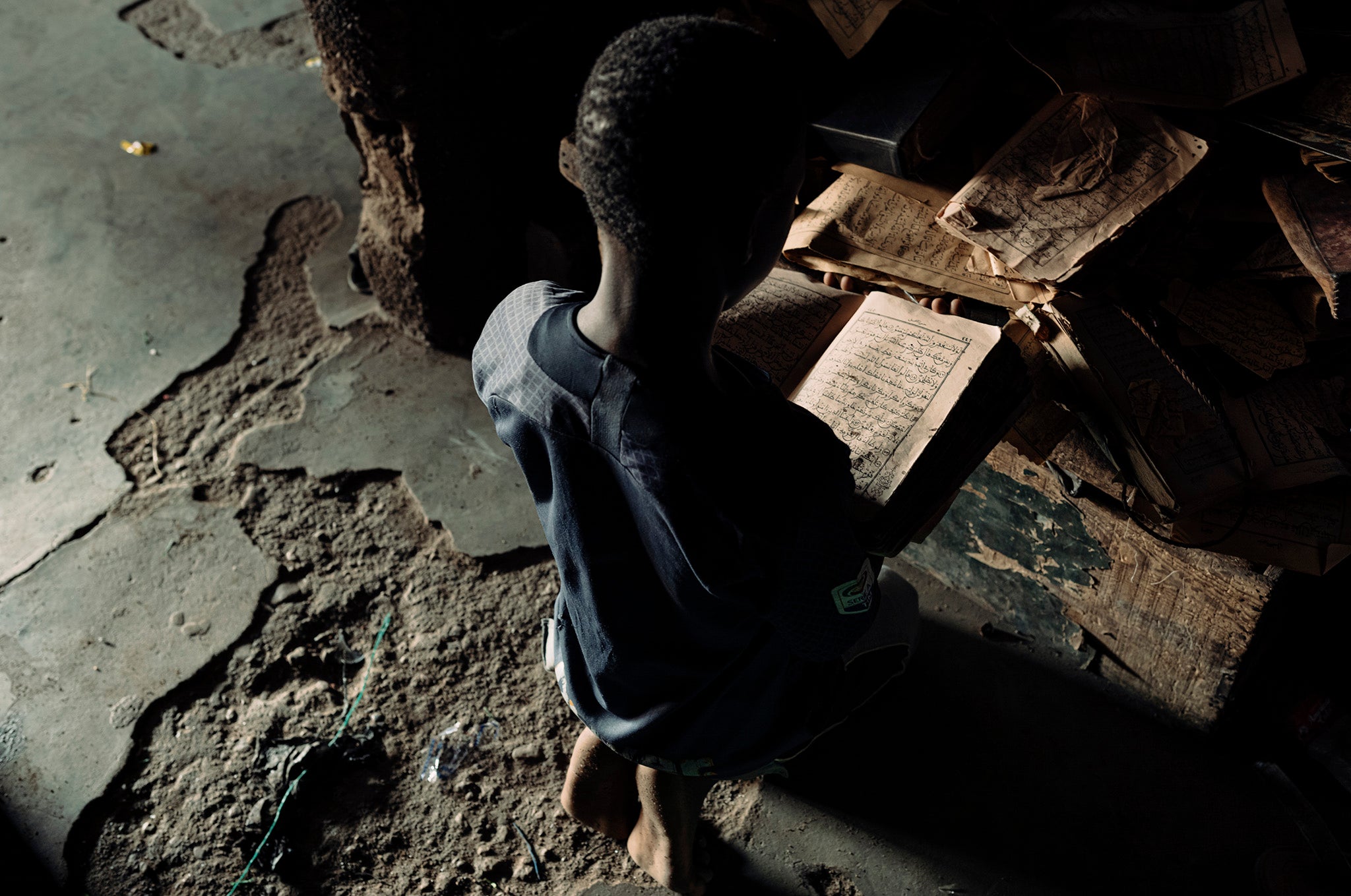

By the time travel corridors had partially opened, I found myself in Mali. This country has endured extreme instability since 2012, with ethnic and tribal conflicts, rebel groups vying for territories in the north, deep-seated corruption in past governments, military coups and the rise of Islamic insurgency across the entire Sahel. The aggregate effect has not only pushed Mali into severe poverty, but the closure of nearly 1,500 schools had left 400,000 pupils without education. Children were now even more vulnerable to every type of exploitation imaginable.

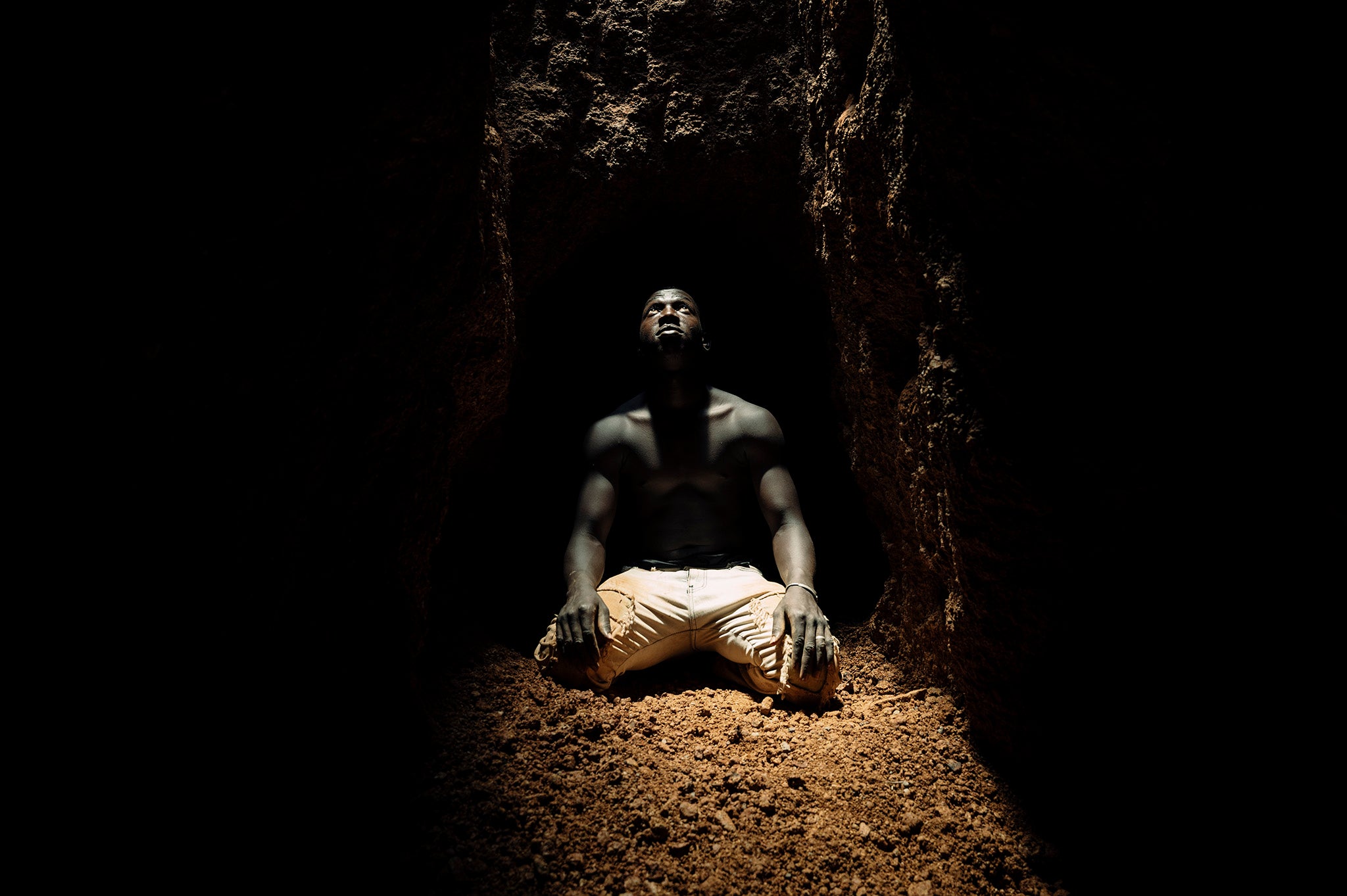

I witnessed children being exploited in the following ways: being sent out to beg through a front of religious schools, being cast off as young as three years old to pick through city rubbish tips, and being trafficked into illicit gold mining operations to meet the demand of negligent but ruthless importing nations.

The world was failing to protect vulnerable children. Why?

Gaza, at the close of its 10-day conflict in May, is where I found myself trying to understand the real human collateral in conflict across its four wars. That manifested itself in the story of six-year-old Saleh. He was walking to buy some bread when an Israeli tank indiscriminately fired a shell into his residential neighbourhood. It shattered the bones in his right arm and blew off his right leg below the knee.

The world continued to watch from the sidelines as the people of Gaza suffered such injustice. Why?

Those small cracks I had started to feel in my mental faculties were now opening up at a rate of knots and for the first time, I was left powerless to suppress them. Inconsolable.

Holding the world to account by showing the atrocities of mankind takes an enormous toll on your heart, mind and entire support network. Storytellers are taking big risks and decisions at times, which barely resemble being of sound mind. Yet without hesitation, they continue to do it.

As a child I believed I could change the world. Idealistic? Perhaps. However when I was old enough I knew I would seize the opportunity. So I did.

But how do I feel about my work today? Heading into 2022 I can only describe my feelings as being bewildered, exhausted and, to my shame, defeated.

After many years documenting this work, I am heading into this year, with it being my last: playing Russian roulette for the final time. I have failed to make any serious changes or influence the way society views the world. The constant noise of ‘Why’, has become louder and louder. Because of that incessant question, I have lost perspective that through all the mayhem, chaos and human suffering we do live in a beautiful world.

Some might ask: why not quit now? Photojournalists and journalists are just not wired like that. Inherently they believe that just one picture and one big story, aligned at just the right time – might make us look up and away from our mobile phones and the ether of social media, and return us to watching or reading news that matters.

I am risking it all to see if I can turn those childhood ideals and dreams into reality. Beyond this I personally owe it to myself and my loved ones to be more present, saving them the torment and anguish that each trip I pack for could well be the one from which I do not return.

If those who were elected in their respective countries, who promised to put people first, did just that, the world would be in a far better state.

Until that happens, those courageous men and women around the world who carry a camera or a notebook, as well as a raft of agencies, foundations and international non-governmental organisations – who refuse to give up on humanity – will continue to risk all to force a change.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments