How do we design motherhood?

Motherhood has long been something overlooked by design institutions, despite it being crucial to everyday life. A new book and exhibition is challenging this, writes Eve Watling

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.From furniture to sports cars, the art of design is widely appreciated. Yet, according to a new book from MIT Press, design remains woefully overlooked when it comes to fertility, birth and parenthood.

“They should be among the most well-considered design solutions. Yet these tools, techniques, systems, and speculations receive almost no attention in design history classrooms,” writes Michelle Millar Fisher and Amber Winick in their forward to Designing Motherhood: Things That Make and Break Our Births.

The design historians point out that MoMA has never had any designs related to human reproduction, pregnancy, or birth from the perspectives of women-identifying or trans people in its almost nine decades of collections and displays. “Many public forums have yet to fully embrace maternity as a topic worthy of serious inquiry,” they say. “Instead, the subject is treated furtively or as unimportant – as something beneath debate or lacking in intellectual content.”

A large contributor to this, according to Designing Motherhood, is a disregard for women’s needs. “Motherhood was a field hiding in plain sight, obscured by its own ubiquity and sidelined by everyday sexism,” says Alexandra Lange in the book’s forward.

She notes that innovators in the field of maternity design were often men who didn’t parent or consider the comfort, or sometimes even the basic humanity, of the women who would use their designs. “Dr J Marion Sims, considered the father of modern gynaecology, who only achieved that renown by testing his unproven surgical methods on enslaved black women,” Lange writes.

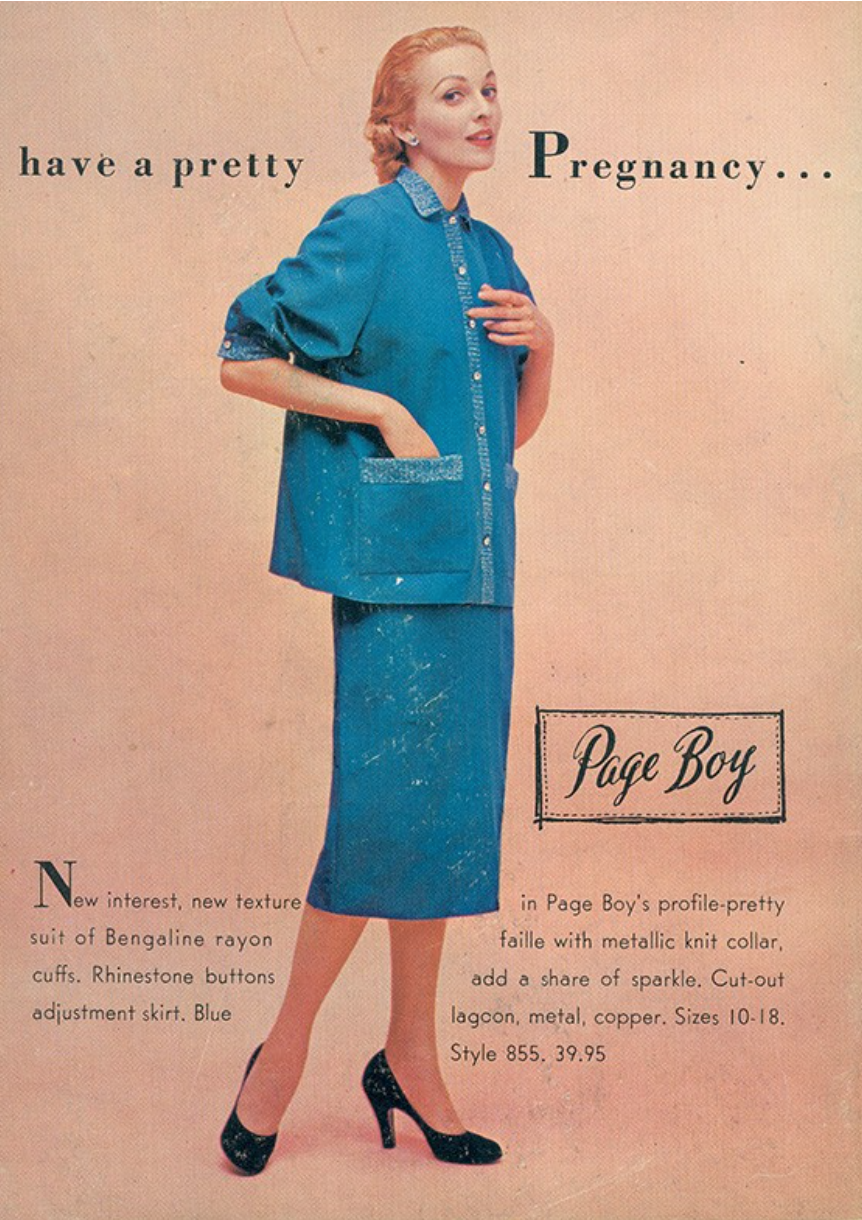

Aside from addressing past and present injustices, Millar Fisher and Winick hope to let people find knowledge and joy in the overlooked history of design for mothers. Their book, which is accompanied by two exhibitions in the US, covers population policy posters all the way to pushchair design, from the bizarre to the genius to the aesthetically beautiful.

One chapter details the history of the menstrual cup, which started life in 1867 before commercial pads and tampons existed. It is described in Designing Motherhood as “a kind of deflated balloon attached to a wire that passes down the vagina and is kept in place with a belt.” It eventually made it onto the market in the 1930s after a much more streamlined redesign by a former Broadway actress, inspired by preserving her white silk costumes.

The menstrual cup’s fortunes tell us about the times we live in. Its new form in the 1930s reflected women’s increasing need for mobility and convenience, while the newer silicone iteration, recently released by sanitary giant Tampax, materialises a pressing need for sustainability. Although the original concept is old, many women today are encountering the product for the first time thanks to its new improved functionality. According to Designing Motherhood, “the design asks us to reimagine, if not jettison entirely, our preconceived notions about how best to manage our periods.”

Some reproductive objects have far darker histories. Use of the Dalkon Shield intrauterine device (or IUD), popular in North America in the early 1970s, resulted in pelvic inflammatory disease, hospitalisation and infertility for many.

In the book, activist Loretta J Ross describes her heartbreaking experience with the device, which led her to be hospitalised and have a total hysterectomy at the age of 23. She sued the company that produced the IUD, who had known their design was problematic before releasing it, and won. The book touches on other heroines of reproductive design, such as New York–based graphic designer Margaret “Meg” Crane, who invented and designed the first home pregnancy test despite antipathy from her male colleagues.

The sprawling book, which contains over a hundred designs in the form of ad clippings and oral histories is endlessly fascinating. Ultimately, it asks for the type of products the people who give birth deserve. “We want readers to laugh, bristle with indignation, or sigh with disbelief at the things individually or collectively endured – and that are begging to be addressed by designers, and by us all,” write Millar Fisher and Winick.

Designing Motherhood: Things That Make and Break Our Births is available to order from MIT Press. The accompanying exhibition is to open in September at the Centre for Architecture and Design in Philadelphia.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments