I’m a Yale educated academic and this is why Taylor Swift should be studied like Jonathan Swift

Academic studies of the merits of Taylor Swift’s lyrics are not the Mickey Mouse courses you might think they are, argues Dr Clio Doyle – and disagreeing with her just proves her point

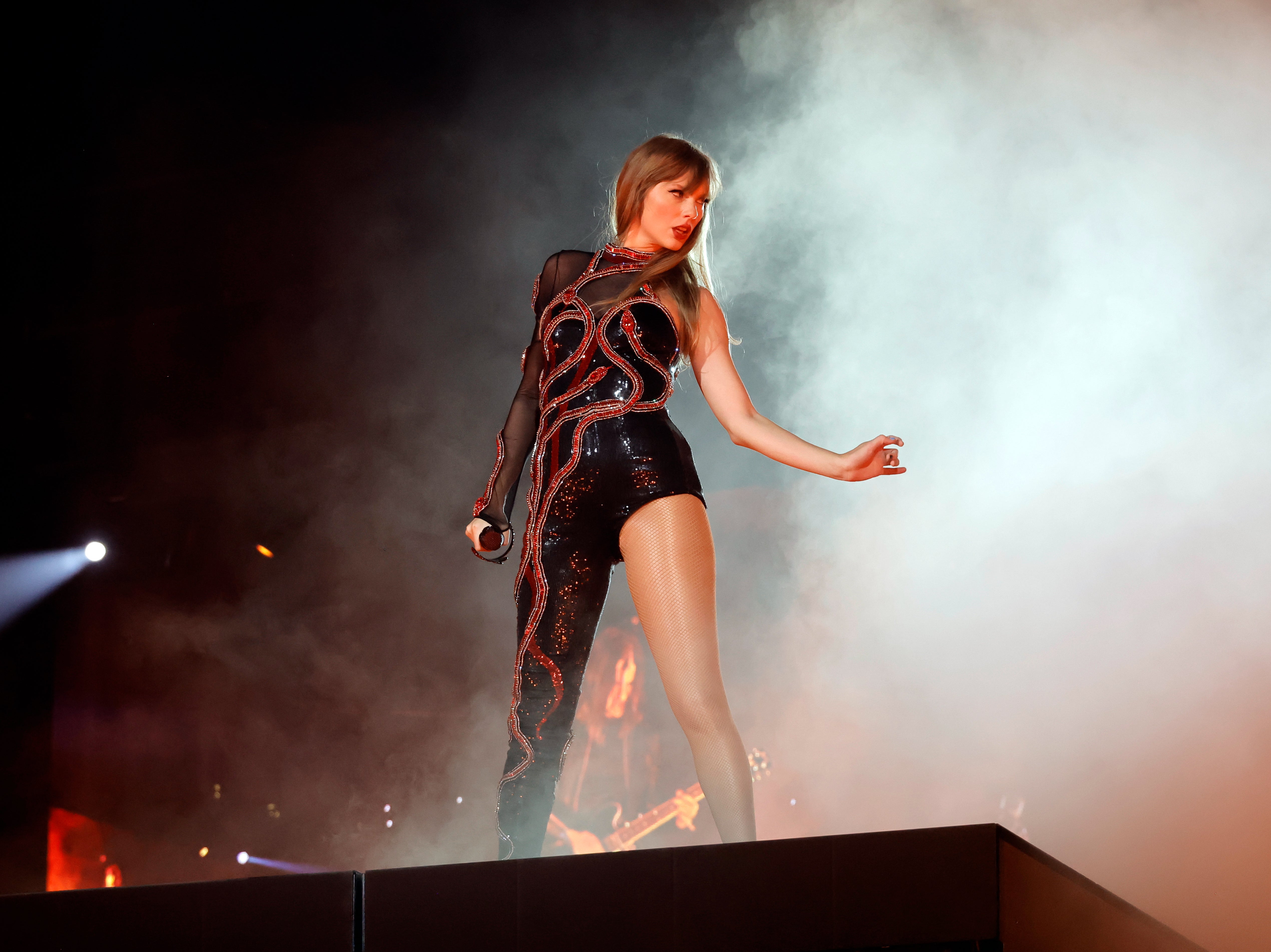

On the day before the Liverpool leg of Taylor Swift’s Eras tour, over a hundred people will attend “Tay Day”, a now soldout academic symposium on her work. Academic conferences and symposia on Taylor Swift are – to quote a song title from Red (Taylor’s Version) – nothing new; they are now being offered worldwide, from the United States to Australia.

In fact, only last week I was just one of many academics asked to present at a conference on Swift and feminism organised by Dr Claire Hurley at the University of Kent’s Canterbury campus.

Like many people studying Swift, I came to this field through a somewhat circuitous route. I have a PhD in English and Renaissance studies from Yale and currently work as a lecturer in early modern literature at Queen Mary University of London.

But in 2021, I started a podcast that used critical theory and has now grown into the book I am working on, Dear Reader: Taylor Swift and the Idea of English Literature in which I argue for the serious literary study of Swift.

The way fans read and discuss her work is often very similar to how we ask students to engage with the texts we teach in literature classrooms. Fans track Swift’s references to older literature such as the poetry of William Wordsworth and Emily Dickinson, analyse the way she self-consciously positions herself as an author, and closely read her work to find in it a dense network of allusions, revisions, and slowly changing metaphors.

These discussions often lead to classic questions of literary theory: whether there is an essential “canon” of literature; is there such a thing as literary value, and to what extent our knowledge of an author’s biography should influence the reading of their work.

Taylor Swift is interesting from an academic perspective because her work provides an entry point into these basic theoretical questions. These are also the questions I ask my summer school students in the class that I lead on “Taylor Swift and literature” at Queen Mary. I designed this course because I feel the interpretative possibility in the work of Swift is similar to much of the literature I engage with.

Much of my previous academic work is on pastoral literature – often about nature, shepherds, and the vicissitudes of love and the seasons – that the critic William Empson memorably described as the result of “putting the complex into the simple”.

I am particularly interested in texts that show a certain recalcitrance to being interpreted, even texts that – like the eclogues of the obscure Tudor poet Alexander Barclay – are aware of, and furious about, their own limitations. Although Swift differs immensely from Barclay, I find that her work offers the challenge of a surface simplicity that hints at complexity.

In one episode of my podcast, Studies in Taylor Swift, I read the lyrics of her song “seven” next to a poem by Robert Frost called “Birches”. Both texts describe the speaker as a child swinging in a tree as a kind of idyllic, innocent experience from the vantage of the speaker’s wistful adulthood.

In “Birches,” the speaker’s description of this childhood pastime is revealed as violence against the natural world, a wearing down of it in search of a kind of artificial transcendence that anticipates the world’s own eventual wearing down of the adult body.

In Swift’s song, the speaker longs for a time before she was able to understand the violence of adulthood, a time when she misread what seems to have been the unhappy family situation of a friend as an occurrence of the supernatural.

There is a kind of cruel, nostalgic ferocity in both texts that accepts but refuses to fully embrace the responsibilities that come with living in an ageing body

When her seven-year-old self reaches her “peak” as she swings in the trees, we are asked to see this as a purely personal “peak,” one that achieves – and desires – no responsibilities, just the solitary pleasure of ascending into the treetops.

There is a kind of cruel, nostalgic ferocity in both texts that accepts but refuses to fully embrace the responsibilities that come with living in an ageing body. These texts about climbing high up in the trees achieve in themselves a kind of precarious balance, between the impossible desires of youth and the dull knowledge of adulthood.

Students I have supervised have compared Swift to Romantic poets such as Percy Bysshe Shelley and Charlotte Smith and to 20th-century poets such as Sylvia Plath. It is certainly worthwhile to consider both the influences of other writers on Swift and the similarities in her career and public perception compared to theirs.

But I also ask students to think about where the desire to compare Swift’s work to that of other writers comes from; for example, we study a few versions of an internet quiz that asks whether Shakespeare or Swift wrote a particular line and discuss why the quiz has been compiled and what argument it is being made about literary value.

I am often asked whether Swift’s work will endure, in the way that some texts from the past are still commonly read while others are forgotten. I am torn between two responses. The first is that we can speak only to and for the present.

The future will select the texts that speak to its own challenges and limitations.

Many of the texts we currently study, from Elizabethan plays to early novels, were not highly valued or respected in their time, and contemporary readers would have been hard-pressed to anticipate our interest in them.

But, I also believe that one of the most exciting things about English literature as a discipline is that it allows you to take on any text at all and prove that it is worthy of study. Good criticism reveals – as much or more as it responds to – the deep questions and ambiguities within texts. It is easy to dismiss a text until someone shows you exactly why it interests them and that is the case for Taylor Swift as it ever was for Jonathan Swift.

It is very clear that many, many people are interested in Swift right now. If you want to know why, you may be able to find some answers at a conference near you.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks