Music review: Jarvis Cocker, The Big Melt, The Crucible Theatre, Sheffield

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.When Jarvis Cocker last stood on stage in Sheffield it was with Pulp - for supposedly the last time in the UK - in December, thrusting confetti cannons into the crowd, exiting to "White Christmas" as the commodious building exploded with snowflakes in their sparkly thousands.

Cocker returns, somewhat more reservedly, with Pulp and friends (including Richard Hawley), as musical director for a one-off performance at Sheffield Doc/Fest of The Big Melt, a film documenting 100 years of stainless steel, a product rooted in Sheffield ("Steel City"). The film raids the BFI archive for footage that glides between the fiery and raucous manufacturing processes and the lives that existed behind it.

The group also includes The Forgemasters string quartet, the City of Sheffield Youth Orchestra and the City of Sheffield Brass Band. Opening with ‘Being Boiled’ by the Human League, the strings swell and soar, adding a fluidity and polished grace to the song’s original stabbing, synth-riddled core. Other re-workings nod to the city’s sonic lineage, running parallel to the film’s portrait of Brits as idiosyncratic but loveable oddballs over the last century, via everything from the BBC Radiophonic Workshop to music from Kes.

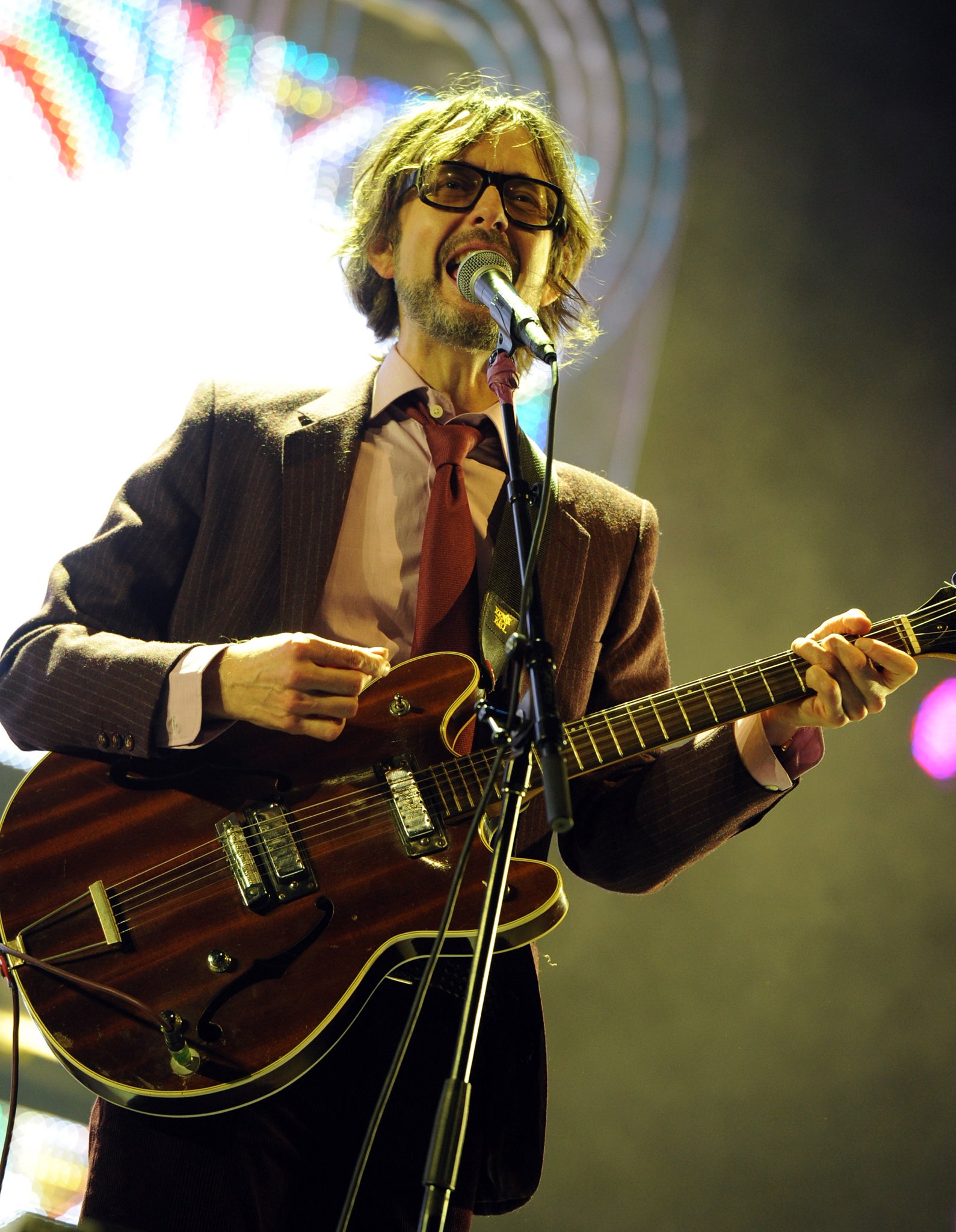

Cocker fits the role of conductor perfectly, approaching it with typical buoyance, magnetism and camp splendour. He doesn’t simply tell the band to stop playing with a surreptitious nod or slight hand movement, but thrusts, jigs on the spot and jumps, timing his fall astutely with arms outstretched to signal the cut.

His former guitarist Hawley sits humbly at the back, swaddled in darkness, switching between quiet guitar and delicate lap steel. The brass band, split into two, enter from both side doors of the theatre, bleeding from stereo into thundering mono as they meet on stage floor. Cocker and long-time collaborator Martin Wallace, while recognising the visual power of the film are not afraid to step on its toes and make it a truly cross-over event.

They engage and immerse us in dance-charged grooves, poignant harp flutters, mandola, saw, turntables and Cocker hollering into something that emulates the fractured echoes of someone screaming into a well. It all culminates in a paroxysm of pulverising psych-rock, as flowing molten steel spits bubbling embers on the screen. With each churning movement and burning gurgle comes a sound as powerful and blistering to match.

A remarkable marriage of music, film and British history.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments