David Bowie review, Toy: Alive with the sound of a band in their prime

The spangly-jangly guitars of his youth are exchanged for the tougher, metallic sound of the new millennium. His richly self-aware vocals offer mature validation to the fear and isolation he expressed in so many of those early lyrics

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

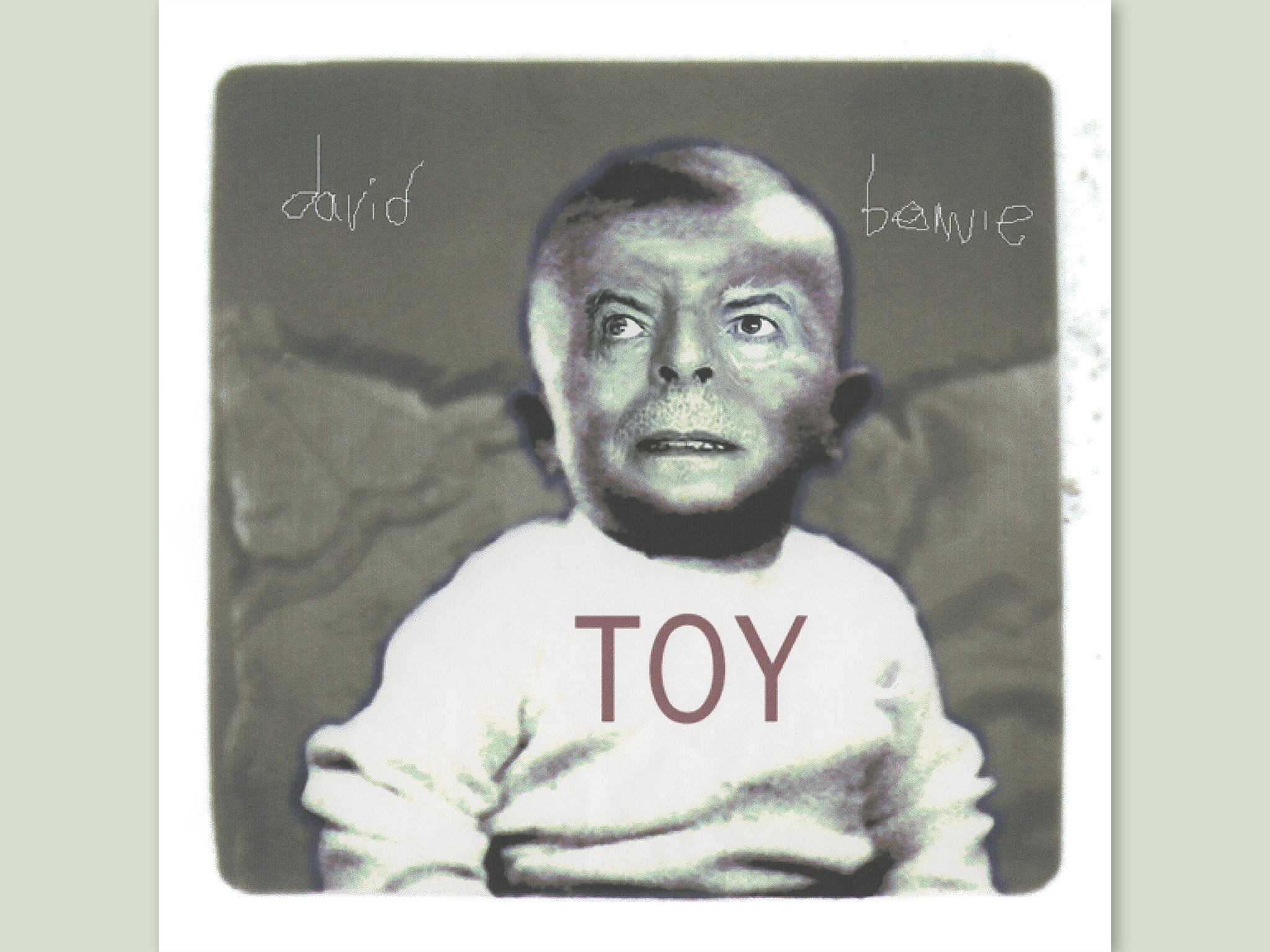

Your support makes all the difference.A “ghost album” is how Tony Visconti describes Toy, David Bowie’s 2001 re-recording of songs that were mostly written in the Sixties. It must feel that way to the American producer, who first befriended Bowie in 1967 and worked with him on and off until his death in 2016. But there’s nothing vaguely ghostly about the confident energy of this record. It’s blood-pumpingly alive with the sound of a band in their prime, fresh from delivering a Glastonbury show hailed by the NME as “the best headline slot at any festival ever”. Bowie was having “a blast, smiling all the day”, guitarist Earl Slick recalled in Dylan Jones’ 2017 biography, Bowie: A Life. “I’d never seen him happier.”

It was a great mood in which to revisit songs Bowie had written in less assured days. He was ill at ease in the swinging Sixties. “Treading water,” he said of that time. You can hear it in much of his output from the decade: angst-ridden lyrics were dressed in twee, groovy-baby and baroque pop arrangements that flopped unflatteringly from their angular frames. His vocals wobbled uncertainly on top, as if he were hovering in a doorway, unsure whether he’d been invited to the party. The Toy re-recordings allowed him to walk back into that scene as a loose-limbed star, laughing and leaning coolly against the doorframe where he once felt “invisible and dumb”. The spangly-jangly guitars of his youth are exchanged for the tougher, metallic sound of the new millennium. His richly self-aware vocals offer mature validation to the fear and isolation he expressed in so many of those early lyrics.

So the once wannabe-jaunty “I Dig Everything” (1966) is transformed into a blast of grungy fun, on which Bowie’s voice swoops low to a gravelly grin. There’s less of the kooky, “Hey Mr Policeman, I’m stoned”, of its original, and more of a clean and controlled stride through a bright urban morning. “Karma Man” has the same attitude, although it nods affectionately back at its roots (and the Buddhist ideas that Bowie later shed) with a little harpsichord plinking over the rich, driving drums. “The London Boys” (1967) sheds the ambitious Bromley boy’s plaintive panic for a smoothly soulful narrative that soars into the arms of a brassy crescendo: “You’re only 17, but you think you’ve grown/ In the month you’ve been away from your parents’ home/ You think you’ve had a lot of fun/ But you ain’t got nothing, you’re on the run.”

Almost as beautiful is “Shadow Man”, a previously unreleased track originally recorded during the 1971 Ziggy Stardust sessions. It’s ostensibly about the Jungian concept of the “shadow self”. But coming from a guy on the verge of developing so many alter egos, fans may suspect the “shadow man” is in fact the shy, suburban Davy Jones lurking behind his extreme, stagey personae. Yet the vocal delivery is the most theatrical on the record: Bowie’s throat tilt up, wolflike, to the moon over lush pools of piano.

To Bowie’s frustration, financial issues at Virgin EMI meant that Toy was shelved. He left the label in 2001 then released Heathen himself (via Columbia) the following year, for which he re-re-recorded some of the Toy tracks. These included a dirgey grind through 1964’s masochistic “Baby Loves That Way”, and a heart-stoppingly beautiful take on 1970 B-side “Conversation Piece”. It’s one of Bowie’s most beautiful melodies, to which he elegantly describes his struggles to connect: “I'm a thinker, not a talker/ I’ve no-one to talk to, anyway/ I can’t see the road for the rain in my eyes…”

The spare precision of the language is much better served by the crisp drumming and graceful strings of the later versions. This is the song on which he sang of feeling “dumb and invisible”, certain “nobody will recall me”. By the time he re-recorded the song, his legacy was assured. But he sings as though he’s realised that doesn’t matter anyway. The coolness of Bowie’s later years lay in his humble humanity. The man singing Toy’s version of “Conversation Piece” feels so casually, intimately present it’s hard to remember he’s a dead rock star. It made me cry, even as Bowie reminded me that “the world is full of life”. If this is a “ghost album”, then I welcome its happy, humane haunting.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments