Reclaiming Amy, review: Documentary is a harrowing account of a family’s grief

The new documentary is told through the eyes of Amy Winehouse’s mother, Janice

“My daughter Amy died when she was just 27 years old”, Janice Winehouse-Collins, mother of Amy Winehouse, quietly says at the start of an intimate new documentary to mark the tenth anniversary of the musician’s death from alcohol poisoning. Directed by Marina Parker, the film is primarily told through the voice of Janice, who wanted to record her memories of Winehouse on camera while she still had the chance: she was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis in 2003 (the same year Winehouse released her debut album, Frank) and since then, her condition has worsened. “She won’t get another opportunity to say what she wants to say,” Richard Collins, Janice’s second husband and full-time carer, tells Parker mid-film.

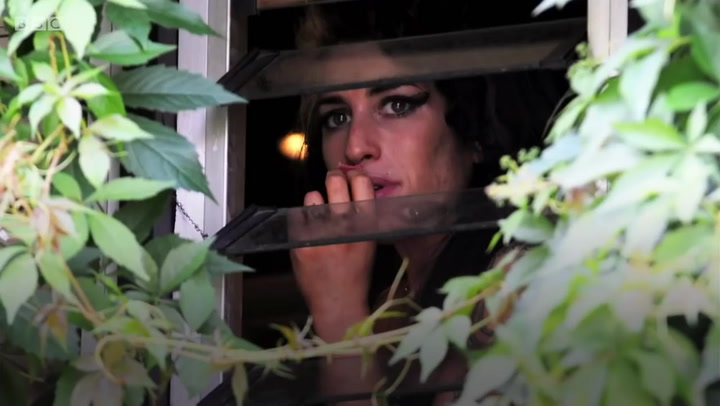

A decade may have passed since Winehouse’s death, but Janice is a mother still deeply enveloped in grief. There are poignant scenes of Janice standing in front of her daughter’s grave, wandering outside the house where Winehouse died, and reflecting in her shrine-like “Amy room” at home, where she keeps her daughter’s awards, gold discs and famous leopard-print shoes. We see inside a lock-up that houses all of Winehouse’s possessions: only recently have Janice and her family felt strong enough to sort through the contents, which have remained untouched since 2011. “Ten years after her death, we’re still grieving,” Janice says, clutching one of Winehouse’s childhood toys close to her chest.

The sadness and speed of Winehouse’s descent is keenly felt in the film’s opening moments. Rare family footage and never-before-seen images of her – singing at school, taking her first forays onto tiny jazz stages, and appearing nervous in early interviews with journalists – are quickly juxtaposed alongside ones of her at Glastonbury and later, winning five Grammy awards for second album, Back to Black. Haunting stills of her hounding by the press follow, as do crushing anecdotes from close friends about her worsening bulimia, declining mental health and addictions in a new-millennium climate where such subjects were still taboo.

Another area sensitively handled by Perkins throughout is Winehouse’s confusion around her sexuality, which is explored via a series of delicate interviews with her friend and former lover, Catriona. “Our relationship was so unique, undefined. We just loved each other very much,” Catriona reveals through tears. “She was confused about what that made her... It’s the thing I think is so fundamental in understanding her and the things that did trouble her.”

Janice has spoken about her daughter before, in her book Loving Amy: A Mother’s Story, which was released a year before Asif Kapadia’s 2015 Oscar-winning biopic, Amy. Reclaiming Amy is a defensive riposte to Kapadia’s work, which the family say led to accusations of them “failing Amy”. Dad Mitch, who received the brunt of the criticism, says the film caused him to have a nervous breakdown while still grieving. He protested the editing of a quote about Winehouse not needing rehab, which led to his vilification: “She didn’t need rehab at that time,” were his original words.

The film raises difficult ethical questions about how the family were treated in the aftermath of Winehouse’s passing and the release of Kapadia’s film. Perkins is certainly persuasive in presenting Mitch as a father who cared deeply for his daughter, but one who didn’t know how to handle the maelstrom of media attention Winehouse faced. As her friends say in the film, Mitch thought he was helping when he “should have been guarded”. Personal and often harrowing accounts from Winehouse’s closest friends reveal the extent of the many futile family interventions that took place behind the scenes, especially from her parents.

The film is careful to avoid blame. Husband Blake Fielder-Civil (who introduced her to heroin) has a fleeting reference, Pete Doherty is cut from the narrative and there isn’t one voice from the music industry. While her family do discuss her very public unravelling on tour and her protestations to perform against their wishes (“nobody controlled Amy”), the question of how a musician signed to one of the biggest record labels in the world was allowed to take to the stage when so desperately ill still feels grimly unanswered. The film does little to interrogate this. More objective voices were needed here, and more time (the film is only one hour in length).

Reclaiming Amy is uncomfortable to watch, though this is ultimately where the film’s power truly lies. Through an unfiltered, candid lens, it shows how much more education, support and resources families need to identify and treat complex addictions, which are often tied to mental health issues like the anxiety from which Amy suffered. The family’s work at The Amy Winehouse Foundation – a charity set up to help those dealing with such issues – shows how far things have moved forward. The ultimate tragedy is how all of this came too late for Winehouse.

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks