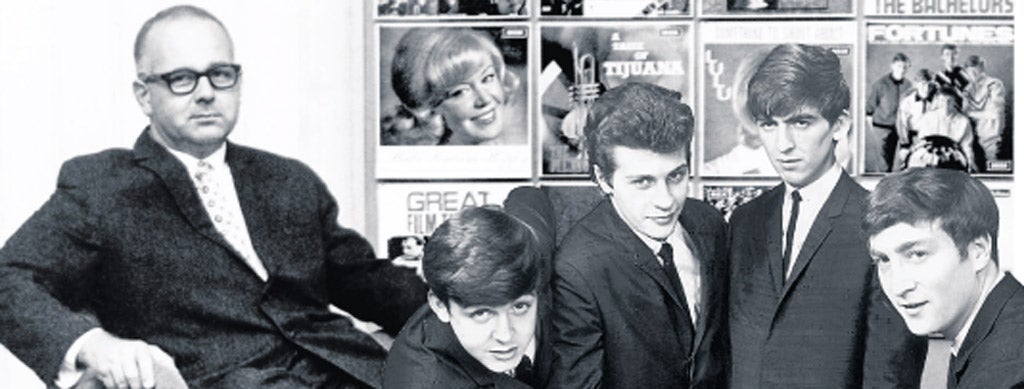

The man who rejected the Beatles

Exactly 50 years ago, Decca's Dick Rowe turned down the Fab Four, so heading an unenviable club of talent-spotters who passed up their biggest chance. But is it all an urban myth? A new book suggests so

"Guitar groups are on their way out, Mr Epstein." With that airy dismissal of the Beatles, supposedly directed 50 years ago this month at the group's manager Brian Epstein, Dick Rowe of Decca made himself unwittingly but enduringly synonymous with catastrophic commercial misjudgements.

He might be honorary president of an unenviable club that includes all the publishers who turned down a book about a boy wizard by a hopeful young writer called Joanne Rowling, and indeed William Orton, the president of the Western Union, who in 1876 decided not to pay $100,000 for Alexander Graham Bell's patent for the telephone, declaring the apparatus little more than a toy. Two years later an anguished Orton admitted that he would consider the patent a bargain at $25m.

There are many members of the misjudgement club, and not a few of them put their mistakes behind them. Rowe himself went on to sign the Rolling Stones, but only because the Beatles, having signed with the EMI subsidiary Parlophone, had demonstrated that guitar groups were very much in.

Rowe was Decca's senior A&R man, its talent-spotter, and whether he was actually responsible for those famously non-prescient words, we'll never know. They were certainly quoted by Epstein, in his 1964 autobiography A Cellarful of Noise. But Rowe went to his grave in 1986 denying it. Of course, to invoke another sensation of the early 1960s, the Profumo affair, well, he would, wouldn't he?

The story will be clarified by Mark Lewisohn, the British author who probably knows more about the Beatles than anyone alive, including Sir Paul McCartney and Ringo Starr, in the forthcoming first volume of his long-awaited three-part history of the group. Lewisohn points out that in some respects it was the Beatles who turned down Decca. Rowe had offered to press their records, but at their expense, not Decca's. And it was probably 50 years ago today, to misquote "Sergeant Pepper", that Rowe received Epstein's rejection of that proposal, in a letter dated Saturday, 10 February 1962.

The Beatles had auditioned for Decca. They performed 15 songs but didn't give a particularly good account of themselves. George Martin, their producer at Parlophone, told Lewisohn that, on the basis of those demos, he would have turned them down, too.

Despite that, and despite the fact that Rowe wasn't even present at the audition, his is the name generally besmirched in the story. And indeed it was Rowe who told his more junior colleague Mike Smith to choose between the Beatles and another group auditioned by Decca around the same time, Brian Poole and the Tremeloes. Smith chose to offer a recording contract to the Tremeloes, not least because they hailed from Dagenham and it seemed more convenient for a London record label to have them on the books than a group from Liverpool.

Like the music industry, the publishing industry overflows with such tales. It was doubtless of little consolation at the time, but JK Rowling was in illustrious company when 15 publishers rejected Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone. "The girl doesn't, it seems to me, have a special perception or feeling which would lift that book above the 'curiosity' level," was one publisher's brusque assessment of The Diary of Anne Frank. More than a dozen others reached a similar conclusion about a book that has now been translated into more than 60 languages, with more than 30 million copies sold. And Stephen King's novels haven't done badly, either, after his first, Carrie, was pompously turned down with the words: "We are not interested in science fiction which deals with negative utopias. They do not sell."

It was old William Orton of Western Union, though, who surely dropped the biggest clanger of all. The Bell clanger, in fact. "After careful consideration," he wrote to the inventor, "while it is a very interesting novelty, we have come to the conclusion that it has no commercial possibilities."

A century later, the San Francisco Chronicle took a similar view of articles about the Watergate break-in by Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein. The Washington Post was syndicating their investigations, but the Chronicle's owner, Charles Thieriot, ruled that "there will be no West Coast interest in the story". Instead, Woodward and Bernstein's increasingly explosive reports were carried by the rival San Francisco Examiner.

Sometimes, selling syndication rights is as disastrous as refusing to buy them. Executives at 20th Century Fox decided to sell to local TV stations the right to broadcast their hit show M*A*S*H, but not for another four years. They calculated that its popularity would wane. It didn't. M*A*S*H made a fortune for the local stations, vastly more than the $25m Fox got for the rights in the first place.

And just to redress the American tilt of these anecdotes, let me conclude with the story of a young script-reader for Central Television, who in the mid-1980s advised his superiors not "to touch with a bargepole" a script for a new detective drama. The writer was a guy called Anthony Minghella. The drama turned out to be Inspector Morse. The hapless script-reader was me. "I Should Have Known Better", as a well-known guitar group once sang.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks