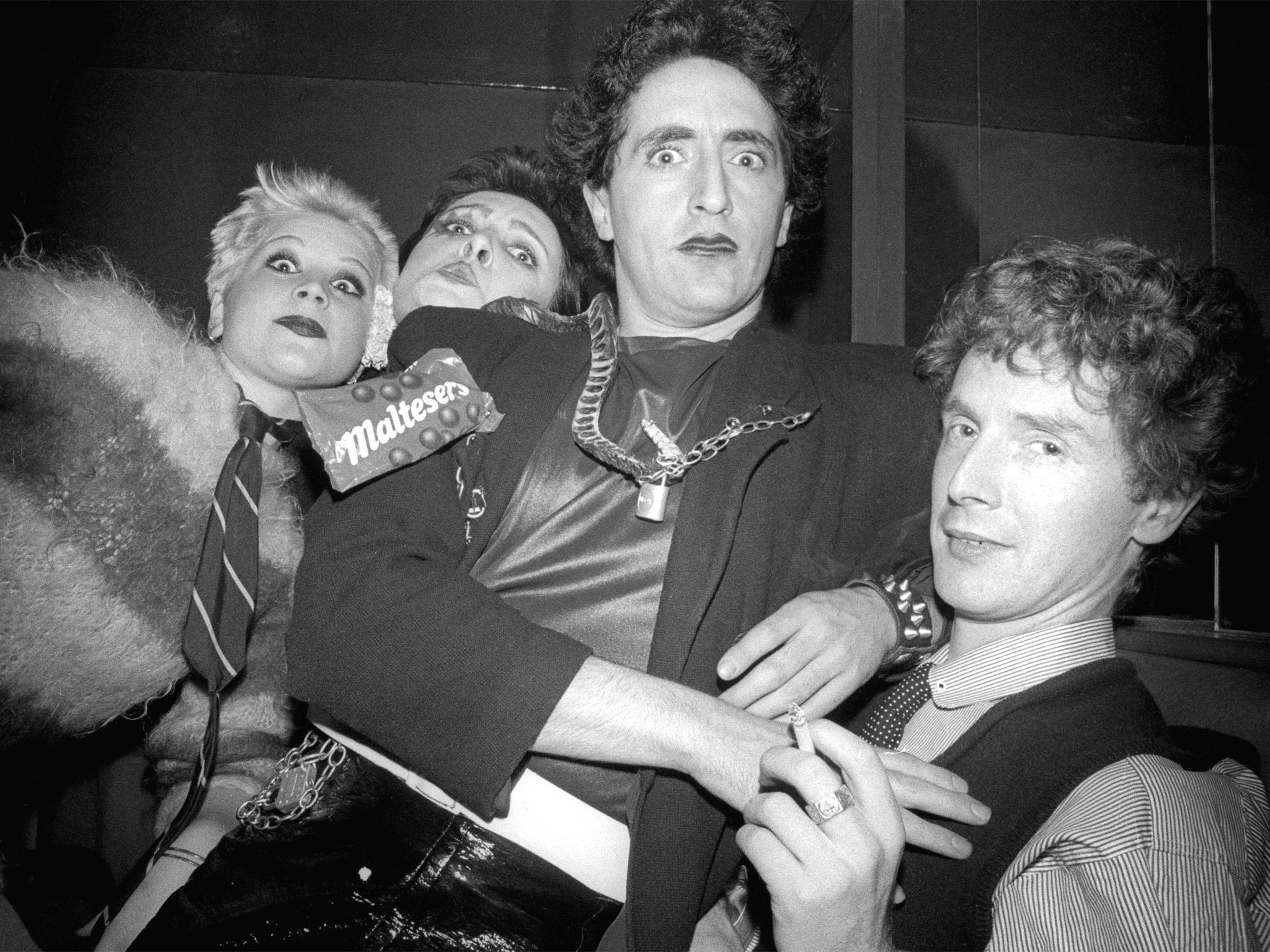

Sex & drugs & herring rolls: Punk’s Jewish roots revealed

London’s forthcoming Jewish Book Week will take an unusual turn with a session on a hitherto unexplored aspect of popular music history

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Punk rock’s transatlantic fuse was lit when Malcolm McLaren saw Richard Hell in New York in 1975. McLaren, whose Jewish family background was in the East End rag trade, was already running the King’s Road boutique, Sex, with Vivienne Westwood.

Hell, originally named Meyers, whose Jewish father had died back in Kentucky when he was eight, was sporting a black leather jacket, torn, scrawled-on and safety-pinned T-shirts, and short spiky hair. This prototype for the Sex Pistols had with his former band, Television, recently turned the club CBGB into the Bowery’s punk hothouse.

The club was run by Hilly Kristal, Jewish too. By 1976, McLaren had parlayed Sex’s success with a radical form of schmutter into the Sex Pistols-led British punk movement. In London and New York, punk had substantial but rarely remarked Jewish roots.

On Saturday, London’s Jewish Book Week will conclude with a talk in which punk veterans including independent label bosses Geoff Travis of Rough Trade and Mute’s Daniel Miller and journalist Charles Shaar Murray will ponder why punk and Jewishness intersected. “There won’t be a unified position,” Murray predicts, “because as the old joke goes, if you put four Jews together you’ll get at least six opinions. But the overlap is to do with an attitude of irony and scepticism.”

In some ways, the presence of The Clash’s Mick Jones and the band’s manager Bernie Rhodes; original Clash and PiL guitarist Keith Levene; Joey and Tommy Ramone and their manager Danny Field; John Holmstrom, the co-editor of New York’s movement-naming Punk magazine; Blondie’s Chris Stein; the Patti Smith Group’s Lenny Kaye and The Dictators among punk’s generals and foot-soldiers merely maintained a continuous thread in pop history.

“There’s a lot of circumstantial evidence,” suggests Norman Lebrecht, whose BBC Radio 3 series Music and the Jews begins next month, “that pop music begins in a conversation on a hot day in New York between the sons of people who fled the pogroms in Russia, and the sons of others who’d fled from the horrors of the slave field in the Deep South, and this common affinity that young Jewish people and black people find for certain rhythms and blue notes, and a legacy of oppression. And commercially, the American music business was founded by Jews, working with black musicians.”

London in 1976, where McLaren and the Sex Pistols made their impact, was a very different place and time to New York’s historic melting pot. But Lebrecht believes the manager’s punk provocations maintained several long Jewish traditions.

“It was McLaren and the next generation of Jews who went around putting sticks in the eyes of the older Jews in the music business,” he says. “McLaren was taught by his family that it is good to rebel. It was a combination of the iconoclastic outsiderhood which is innate in the culture of the Jewish minority, and wanting to be a little bit more cool than just making shirts.”

“Malcolm fulfilled Jewish stereotypes in everything except his actual choice of surname,” Charles Shaar Murray believes. “There are two great Jewish stereotypes – one is the learned rabbi, and at the other end you’ve got the hustler. McLaren was a volatile and paradoxical combination of both extremes. He was artsy, political and very creative, and he was also in the schmutter business. Plus, he fancied himself as Fagin.”

Filtering people such as McLaren through the prism of their Jewishness alone, though, falsely limits their impact on punk, and punk’s impact on them.

Punk, as previous post-war pop culture shockwaves had done, broadened the potential identity of individual Jews, as much as those individuals broadened the culture. Murray, like McLaren, had already had his mind blown by the 1950s and 1960s before throwing himself into punk. His conservative, suburban family background had been shed like an unwanted skin, even as Jewishness remained at his core.

“I guess I liked punk because it was a chance to f*** with the heads of a predominantly gentile establishment,” he laughs. “But it was also a place to be both who you were and who you wanted to be. The Jewish punks who changed their names [as Hell and Joey and Tommy Ramone did] didn’t do so because they wanted to hide the fact they were Jewish. They changed because they wanted to express a total inner self.”

Even the cavalier use of swastikas by Siouxsie Sioux, the Ramones (two of whose members were Jewish, though Dee Dee Ramone’s German family past included Nazis) and even Johnny Rotten (in a shirt from McLaren’s shop) provoked diverse reactions among Jewish punks. “I thought it was dumb and infantile,” says Murray.

“I thought the use of the swastika was a positive thing,” Daniel Miller – whose Mute label helped forge synthpop and the careers of Nick Cave and Depeche Mode in punk’s aftermath – says by contrast, “completely depending on the context. I knew the difference between Siouxsie Sioux and a member of the NF with a swastika tattoo.”

Saturday’s panel has made Miller think hard about the part his own Jewishness may have played in his attraction to punk. His actor parents were refugees from Hitler’s Austria. “My father was also a satirist, and I grew up in that atmosphere,” he says. “I was never going to be an accountant.” But experiencing the questioning 1960s and pop’s epochal impact as a teenager was equally crucial.

“I just was not focused on the Jewishness of what I was doing at all,” he says simply. “I didn’t even know that Geoff Travis was Jewish until a few years after I met him, or McLaren, and I don’t care. It’s not like we were saying, ‘Oh, God, isn’t it weird that we’re all Jewish?’ We felt like we had a job to do, and we were getting on with it. The most important thing was making great records.”

‘The Jewish Roots of Punk Rock’ is at Kings Place, London, on 1 March (kingsplace.co.uk). ‘Music and the Jews’ is on BBC Radio 3 on Sundays at 6.45pm next month

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments