Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

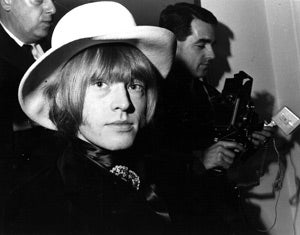

Your support makes all the difference.Forty years after the body of Rolling Stones guitarist Brian Jones was found floating in his swimming pool following a binge of drugs and drinking, police said Monday they are reviewing the case in light of new evidence turned over by a journalist.

Jones' 1969 drowning was ruled an accident, though friends and fans have long insisted the 27-year-old rock star was murdered, and reports have swirled of a deathbed confession by a building contractor.

Sussex police in southeast England said they will examine the new documents and have not yet decided whether to officially reopen the case.

"It's too early to comment at this time as to what the outcome might be," the Sussex duty inspector said, reading a statement over the telephone.

Police did not give further details or name the journalist. The Mail on Sunday identified him as Scott Jones — a free-lancer who is not related to the musician — and said he had handed over 600 documents to police.

Brian Jones was a founding member of the Rolling Stones and reportedly came up with the band's name, taking it from a song title on a Muddy Waters album cover.

"In the beginning, Brian Jones was the real catalyst for the Rolling Stones, the smart, handsome, multi-instrumentalist leader who loved the blues and galvanized the band," Jasen Emmons, the director of curatorial affairs at Seattle's Experience Music Project, said in an e-mail.

But his role started to shrink as the band branched out from blues covers, "and his legendary substance abuse made him less reliable and desirable, although it didn't hurt the Stones' reputation as one of rock n' roll's most dangerous bands."

Jones stood out even among his bandmates for his flashy clothes and prodigious appetite for drugs. But he was quickly eclipsed by swaggering lead singer Mick Jagger and guitarist Keith Richards, whose songwriting propelled the band's popularity.

Increasingly marginalized and drawn to drugs and alcohol, Jones was convicted twice on narcotics charges, avoiding jail by promising to quit his habit.

He left the band a month before his July 2, 1969, death and was replaced by Mick Taylor.

Two 1994 books have claimed that Jones was murdered by a London building contractor hired to help renovate Jones' 11-acre Sussex estate. "Paint it Black: The Murder of Brian Jones," by Geoffrey Giuliano and "Who Killed Christopher Robin?" by Terry Rawlings, said the builder, Frank Thorogood, confessed on his deathbed in November 1993 to killing Jones.

"It was me that did Brian. I just finally snapped," Thorogood was quoted as telling Stones road manager, Tom Keylock, in Rawlings' book. Keylock died in July.

It was not clear why British police did not reopen an investigation after those books were published.

Journalist Scott Jones interviewed the woman who discovered the guitarist's body, Janet Lawson, shortly before she died last year.

In the interview, published in The Mail on Sunday last November, Lawson said that Keylock, who was her boyfriend at the time, was worried about tensions between Jones and Thorogood.

The night Jones died, official reports said there were three guests at his home — Lawson, Thorogood and Jones' girlfriend Anna Wohlin. All three gave statements to police saying Jones had been drinking that evening.

However, Lawson told Scott Jones that police had pressured her and "were trying to put words into my mouth," the newspaper report said.

It quoted Lawson as saying that the evening Jones died, the group had eaten in the early evening, and Jones and Thorogood began fooling around in the swimming pool. A short while later Jones, who was by then in the pool alone, asked her to find his asthma inhaler.

"I went to look for it by the pool, in the music room, the reception room and then the kitchen," she said, when suddenly an agitated Thorogood appeared.

"Frank came in in a lather. His hands were shaking. He was in a terrible state. I thought the worst almost straight away and went to the pool to check. When I saw Brian on the bottom of the pool and was calling for help, Frank initially did nothing."

She said her original police statement did not mention any tensions between Jones and Thorogood, or the fact that Thorogood initally ignored her cries for help because she was "tired, confused and nervous."

Scott Jones also spoke to Bob Marshall, the chief investigating officer in the case. Marshall, who retired in 1974, said he still believed Jones' death was "a tragic accident, a simple drowning."

The title of Rawlings' book, " Who Killed Christopher Robin?," is a reference to Jones' estate, which was formerly the home of the late A.A. Milne, author of "Winnie the Pooh," which features the character Christopher Robin.

The Rolling Stones are one of the most influential and biggest-selling rock bands in the world, with album sales estimated at more than 200 million copies. The band's long list of classic hits include "(I Can't Get No) Satisfaction," "Street Fighting Man" and "You Can't Always Get What You Want."

The band, now made up of Jagger, Richards, Ronnie Wood — who replaced Taylor in 1975 — and drummer Charlie Watts, topped Forbes' list of wealthiest musical performers in 2007, earning some $88 million between June 2006 and June 2007, mostly from their "Bigger Bang Tour." E-mails and phone calls to the groups' publicists and record labels were unanswered Monday.

Meanwhile, Jones' early death continues to feed his reputation long after he is gone.

"It's that mystery surrounding his death combined with the public's fondness for conspiracy theory that keeps Jones' death front and center," Richard Aquila, a professor at Penn State, Erie, who studies social and cultural history, said in an e-mail. "After all, he was a founding member of one of rock's all-time greatest bands — another example of a fallen rock star gone but not forgotten."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments