Music has the power to rock the state, but youth movements will find the state always bites back

The 20th century saw battle lines drawn between music-driven youth movements and the state like none before

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

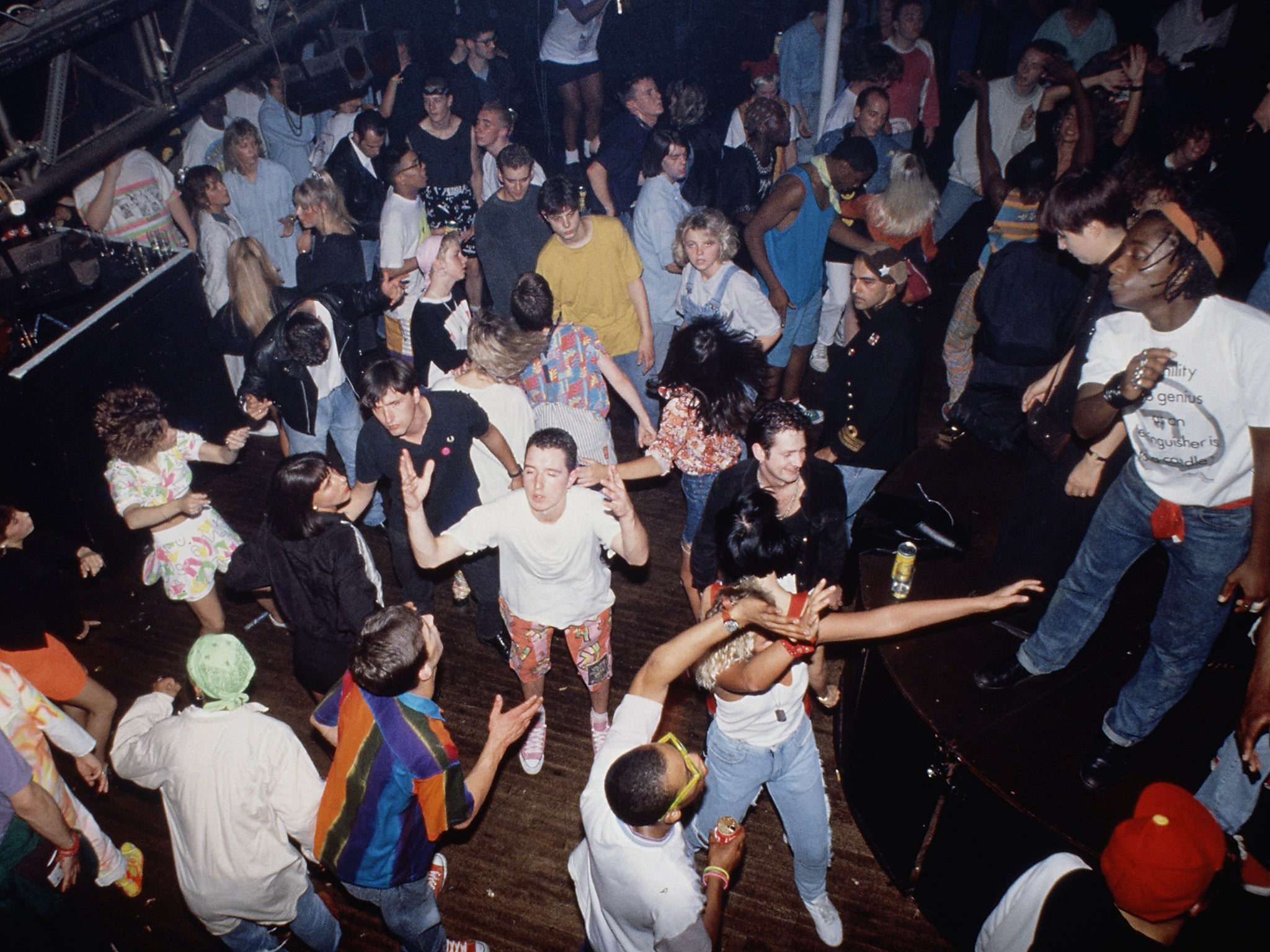

Your support makes all the difference.Among records recently released to the National Archives is a file from the 1980s entitled “Acid House parties” which details the Government’s disquiet over the growing phenomenon of raves: the large, open-air dance events in which thousands of young people, guided by organisers using new technologies such as pagers and mobile phones, descended upon fields to party.

The response was a series of laws imposing strict conditions and harsh penalties, with the 1994 Criminal Justice Act infamously outlawing music “characterised by a series of repetitive beats”. While many at the time may have felt immediate action was required to prevent the collapse of civilisation as we knew it, this was in fact merely the latest in a long line of moral panics over popular music throughout the 20th century.

The cultural mixing pot of jazz, and even traditional music and ballads or bawdy songs in music halls had at some point caused anxiety among the powers that be. But it was during the rock‘n’roll era that this process of music putting the fear into the state was turned up.

Slash the seats

Even before the arrival of Elvis Presley’s gyrating pelvis, fears about rock‘n’roll were brewing from the transgressive collision of Afro-American rhythm and blues, white youths, and sex – all during the fraught racial politics of 1950s America. Crossing cultural boundaries and national borders, rock‘n’roll became a global phenomenon, with fears for the youth of the day gripping almost every nation. The United Nations even convened a special conference in London in 1960 to discuss the problem of juvenile delinquency.

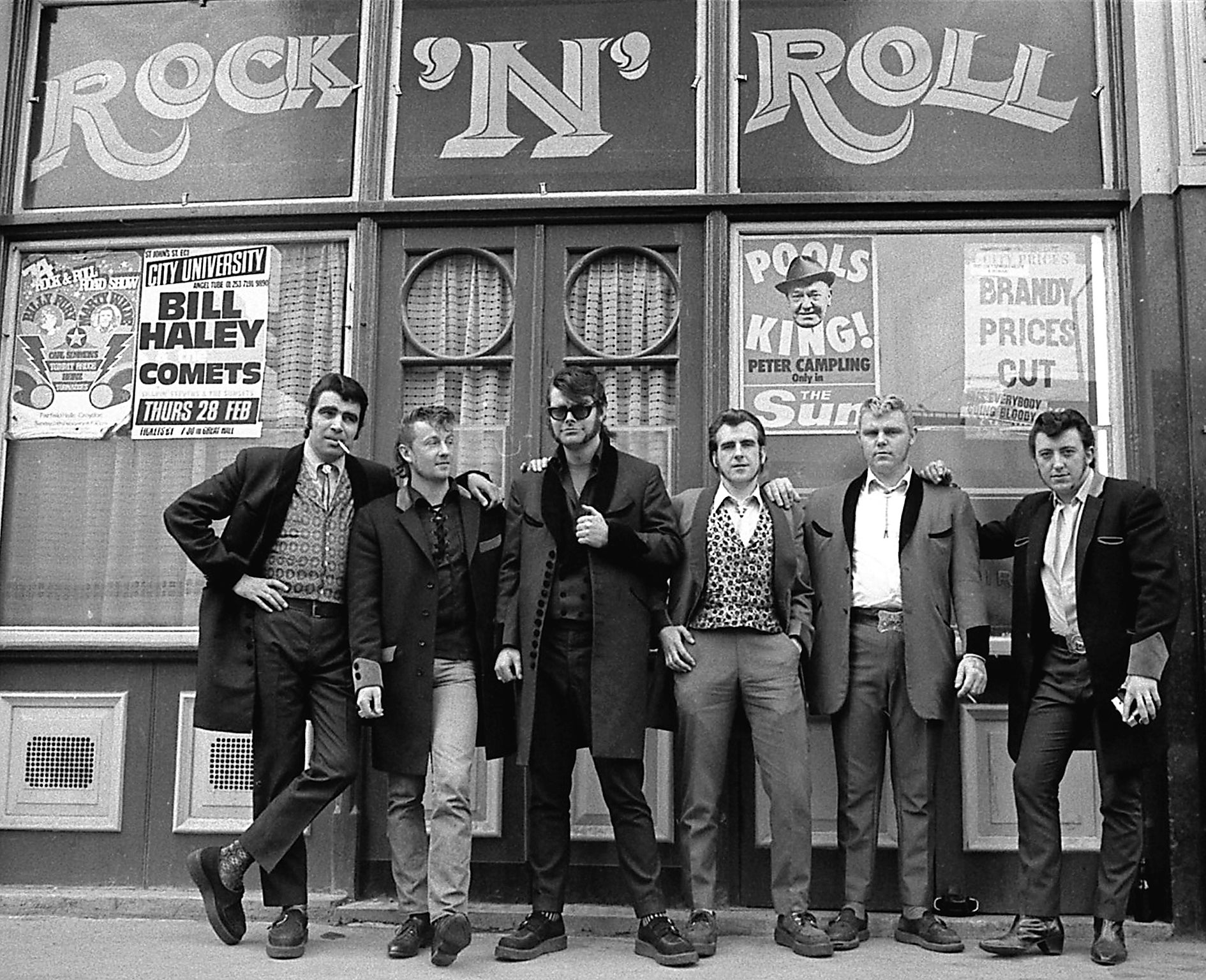

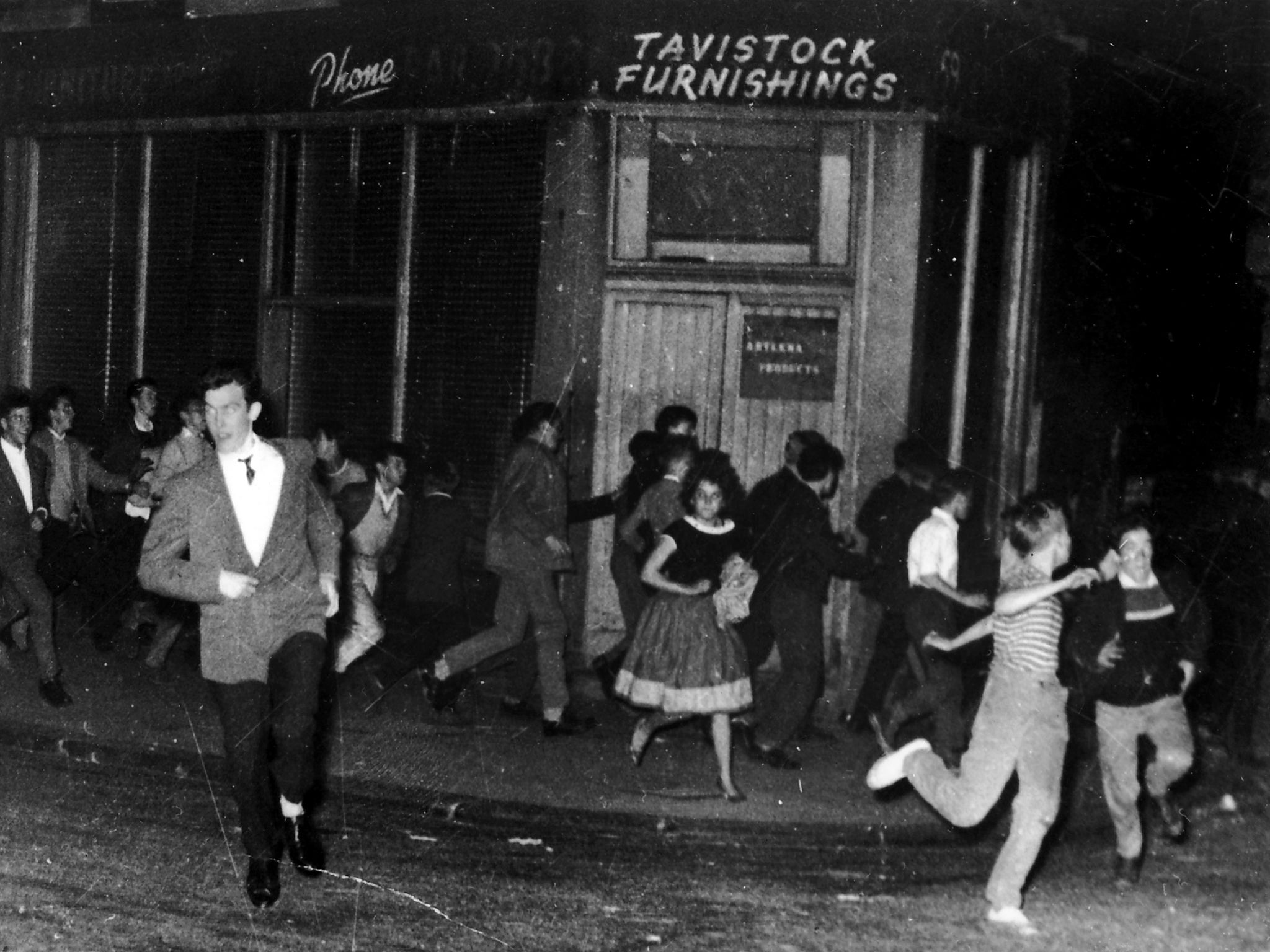

In Britain, the arrival of rock‘n’roll in 1955 collided with a pre-existing panic over the Teddy Boy youth movement, sparked by a notorious gang-related murder in Clapham in 1953. The Teds embraced the new music and the press was filled with reports of them slashing cinema seats while dancing to Bill Haley and the Comets’ “Rock Around the Clock” from the closing credits of Blackboard Jungle – an American movie, ironically, about juvenile delinquents.

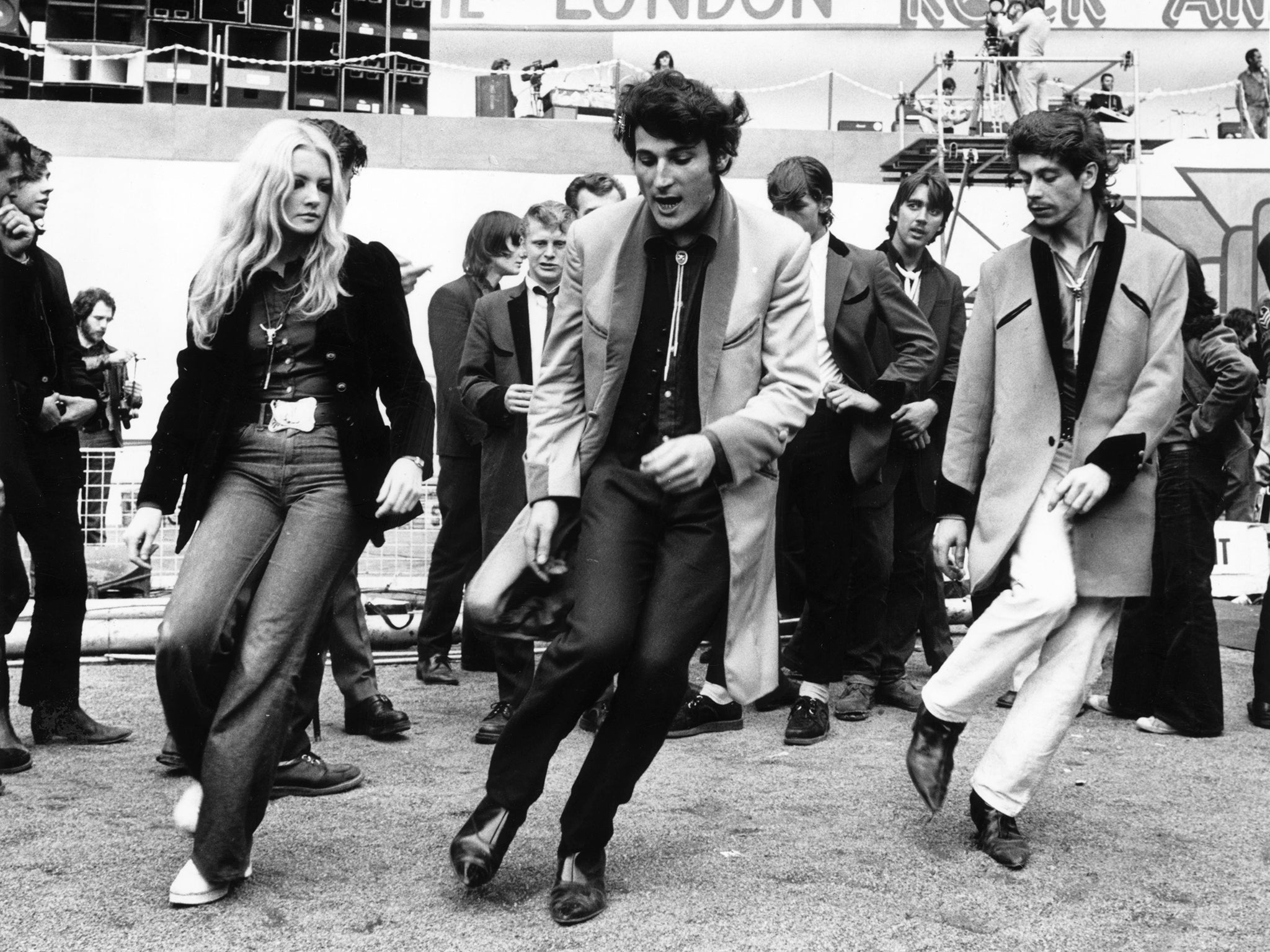

But rock‘n’roll cleaned up – Elvis joined the army, and squeaky clean crooners and apostate rockers like Cliff Richard took the edge off pop music. The next moral panic came with the British Beat boom in 1964, when running battles broke out between mods and rockers in seaside towns. Rockers were the descendants of the Teds, who had abandoned Edwardian frock coats for leather jackets. The mods were associated with bands like The Who, The Yardbirds and the Small Faces, with a sharp dress sense favouring suits, a clear collective identity, and an often undeserved reputation for misbehaviour.

The out-of-touch Conservative government under Alec Douglas-Home in 1964 passed The Malicious Damages Act and The Misuse of Drugs Act, banning the amphetamines that claimed to have fuelled the mod scene. This was the first time an explicit association was made between narcotics and pop music subcultures. From now on, the two would regularly be grouped together.

Busted

Fifty years ago this year, police raided the home of Rolling Stones guitarist Keith Richards and arrested him, singer Mick Jagger and gallery owner Robert “Groovy Bob” Fraser. The trial was a global media event, not least for the behaviour of the judge at the trial who constantly chided and condemned the “petty morals” of the band before jailing them.

The response to the convictions was extraordinary. As well as the expected vocal protests of Rolling Stones fans, the editor of The Times – an “establishment” newspaper – published an incendiary editorial, “Who breaks a butterfly on a wheel?”, attacking the judge for seeking to make examples of the two bandmates. Ultimately Jagger and Richards successfully appealed against their sentences. Although clearing his name was a Pyrrhic victory for Richards, in the light of his subsequent life dogged by heroin addiction and many brushes with the law.

A cascade of music celebrity raids followed, and by 1967 a backlash had emerged against youth counter-cultures on both sides of the Atlantic, with the likes of Mary Whitehouse campaigning for a return to “traditional values”. Medical and psychiatric professionals added their voices to those of the reactionaries, as there were legitimate concerns about the proliferation of drugs: 1967 was the first “Summer of Love”, when the music and art of the era was laced with LSD. Although not all favoured prohibition there was clear evidence of harm that had to be addressed.

Questions linger over the establishment’s targeting of groups such as The Beatles and the Stones, and others such as Jimi Hendrix. The press almost certainly tipped off the police over drug use at Richards’ home, and there is evidence of police collusion with the media. And the establishment itself was not innocent: the Metropolitan Police’s drugs squad later had to be gutted of corrupt policemen after it was discovered that senior officers had committed perjury to defend a known drug dealer. Were pop stars targeted to deflect attention from serious criminals who had the police in their back pocket?

The moral minority

Sometimes the problem was not drugs but obscenity. Even if it seems absurd today, The Beatles song “I am the Walrus” was struck from BBC playlists due to the lyric: “Boy, you have been a naughty girl and let your knickers down”, while The Sex Pistols were forced to argue the precise meaning of the word “bollocks” in court. Elsewhere, anarcho-punks The Anti-Nowhere League and Crass also found themselves in the dock for the use of obscene language.

The most notorious attack on popular music on grounds of obscenity was undoubtedly from the Parents Music Resource Center in the US during the 1980s, who demanded warnings on record sleeves alerting parents to explicit lyrical content. Their list of what they regarded as the most egregious examples of obscenity, known as the “filthy fifteen”, contained both heavy rockers and comparatively tame pop acts.

The result of a congressional enquiry was an agreement by the Recording Industry Association of America and manufacturers to add the now iconic “Parental Discretion Advised” sticker on certain records. Not only did this often act as an incentive to adolescent purchasers rather than a warning, but there is significant evidence that the industry agreed not as a sop to the moral lobby but in return for a levy on blank cassette tapes, ensuring the industry could profit from the practice of home taping records.

Folk devils

Sometimes it was not the musicians but their fans that worried the authorities. The skinhead, punk, rasta and raver scenes have all been viewed as, in the words of the sociologist Stanley Cohen, “folk devils”: those who seemed to champion disorder. Authorities struggled with the question of whether bands are responsible for the actions of their fans.

Two famous cases from the 1980s saw heavy metal legends Ozzy Osbourne and Judas Priest blamed for the suicides of several fans. It was claimed that Judas Priest had inserted a subliminal message into the track “Better You Than Me”, and that Ozzy’s track “Suicide Solution” was an incitement to suicide – something Osbourne denied. Both court cases failed, but raised important questions about the relationship between fans and bands. Even after the end of the conservative-dominated 1980s, the 1997 Columbine High School massacre in Colorado was blamed on Marilyn Manson’s music in much the same way.

The last decades of the 20th century were the high tide of moral panics over popular music, with almost every development in musical subcultures generating unease and outright hostility from the authorities, morality campaigners, and opportunistic newspaper editors looking for the next trend to decry and sensationalise.

In recent years the potential for music to shock or generate controversy seems to have lessened. Even members of boyband One Direction escaped largely unscathed from tabloid exposure about recreational drug use, which a generation earlier had ended the careers of the likes of East 17.

Certainly, there is greater toleration or acceptance of the harder edges of musical cultures. But the passing of the Psychoactive Substances Act 2016 shows that anxieties about youth culture and behaviour are still part of the political landscape. And it takes only a fraught atmosphere, the search for a scapegoat, and ill-judged responses from popstars to turn a headline into the next moral panic.

Clifford Williamson is a senior lecturer in contemporary British and American history at Bath Spa University. This article first appeared on The Conversation (theconversation.com)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments