The strange and surreal aftermath of John Lennon’s murder

The fatal 1980 shooting – 43 years ago this week – became a defining moment in popular culture. But, David Lister asks, can a new documentary really shed any new light on the Beatle’s assassination?

They say, and they’re right, that just as with President Kennedy, everyone who was alive can remember where they were when they heard of John Lennon’s murder. We can remember the moment, the rest of the day and the ensuing week of worldwide grief and adulation.

Personally, I recall hearing on the car radio, in the middle of 9 December, three Beatle songs being played in a row and vaguely thinking it a little odd – as this was the one period in the last 60 years that they weren’t actually that fashionable. Then, just before the Six O'Clock News on BBC TV, I realised the reason, when the host of the BBC magazine show Nationwide, Michael Barratt, came on and said that grown men had been crying in the street. The subsequent news bulletin made it all clear. Lennon had been gunned down outside his New York home the night before.

Now, Apple TV is airing a three-part documentary, Murder Without a Trial, narrated by Kiefer Sutherland, which will reveal hitherto unknown information about Lennon’s shooting on 8 December 1980. Much is already known, obviously, about the deranged fan Mark Chapman getting an album autographed by Lennon outside the ex-Beatle’s apartment in New York, staying there until he returned from the studio that night, then firing several bullets into him, and staying until the police came and found him with a copy of The Catcher in the Rye.

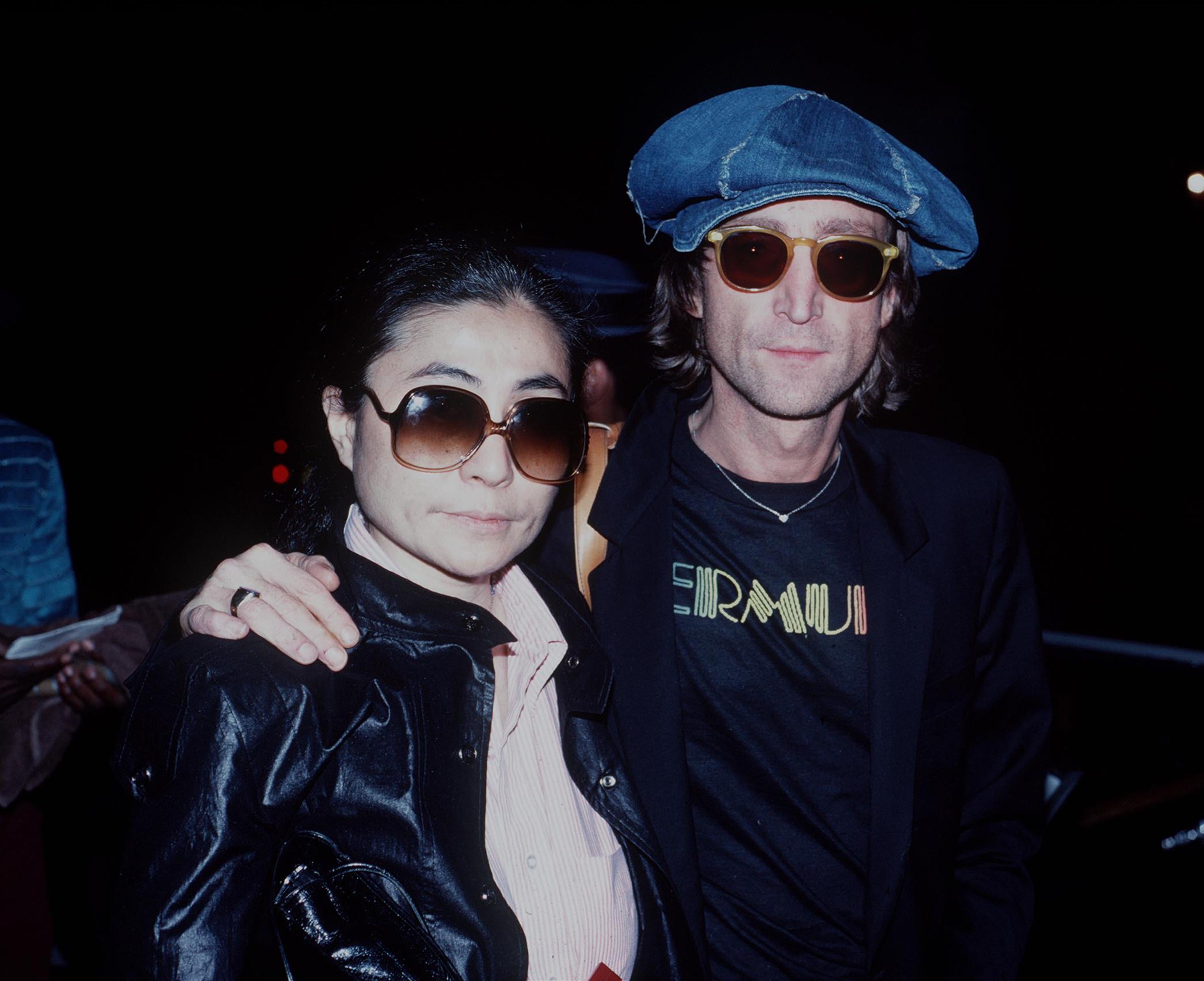

Other information took years to come out, and some was quickly buried. It took many years before Stephan Lynn, the hospital doctor with Lennon at his death revealed what he said was Yoko Ono’s reaction when he told her that her husband had died. According to him, she flung herself to the floor and banged her head repeatedly and painfully on the ground. One must not really pass judgment on any form of grief when a loved one is taken so cruelly, but this certainly seemed unusual, and it has to be said that Yoko Ono has disputed the doctor’s account, saying she did not bang her head but was determined to keep herself calm for her son’s sake.

A day or two later Lennon’s first wife, Cynthia, telephoned Yoko to ask about the funeral. Whether this episode is in the Apple documentary might depend on the extent to which it had Yoko’s cooperation and authorisation. What actually happened was Cynthia said to Yoko that she and Julian, her son with John, wanted to come to the funeral. Yoko replied: “We’re not exactly old schoolfriends, are we Cynthia?”

Cynthia, now also dead, recalled the conversation some years later and said that she was flabbergasted and left distraught by that reaction. Julian was just 17 and would have to make the flight to New York and back on his own, which Cynthia was very unhappy about. In the event, there was to be no official funeral.

Paul McCartney’s reaction is also one he would come to regret. He emerged from a recording studio, where he had just been listening to music and reflecting on his friend, songwriting partner and so much more, to be met by a wall of cameras and microphones. “It’s a drag isn’t it,” he said. A simple enough reaction in the argot of the time, but woefully inadequate.

In Barry Miles’s 1997 authorised biography of Paul, Many Years From Now, McCartney looked back and said of the “It’s a drag” comment: “It looked so callous in print. You can’t take the print back and say ‘Look, let me just rub that print in shit and pee over it and then cry over it for three years, then you’ll see what I meant when I said that word’. When I got home, I wept buckets in the privacy of my own home.”

When I interviewed Paul in 2012, we talked about it, and he said partly to me and partly I think to himself, simply but movingly: “He died so tragically young.” As both he and Beatles fans had got older, a lot older, the truth had finally sunk in of how ludicrously young John was when he was killed, and how huge the wasted potential was.

Ringo was the only Beatle to go to New York to see Yoko in the immediate aftermath of the death. There was no funeral for Lennon, just a private cremation, though Yoko and Sean, her young son with John, held a candlelit vigil. George gave his tribute in song the following year, with the single “All Those Years Ago” (”you were the one I looked up to all those years ago”). It wasn’t a particularly big hit.

And then there was the strange and surreal week in Britain after the death. Obituaries for John inevitably turned into obituaries for The Beatles. Youth was relived and mourned, seemingly everywhere. Tales and music were swapped. I recall a friend, unbidden, making me a cassette (it was 1980 remember) of Lennon songs, a ritual that was probably widespread. Lennon’s “Imagine” was re-released and went to No 1. Shortly afterwards, Roxy Music recorded Lennon’s song “Jealous Guy”, which also went to the top of the charts. Newspaper and TV tributes were everywhere.

But, significant was the comment at the time of Maureen Cleave, the former Evening Standard pop writer who interviewed The Beatles in the Beatlemania years and became especially close to John. She said that she had read thousands of column inches about him during that week of mourning, “but nowhere did I recognise the man I knew”.

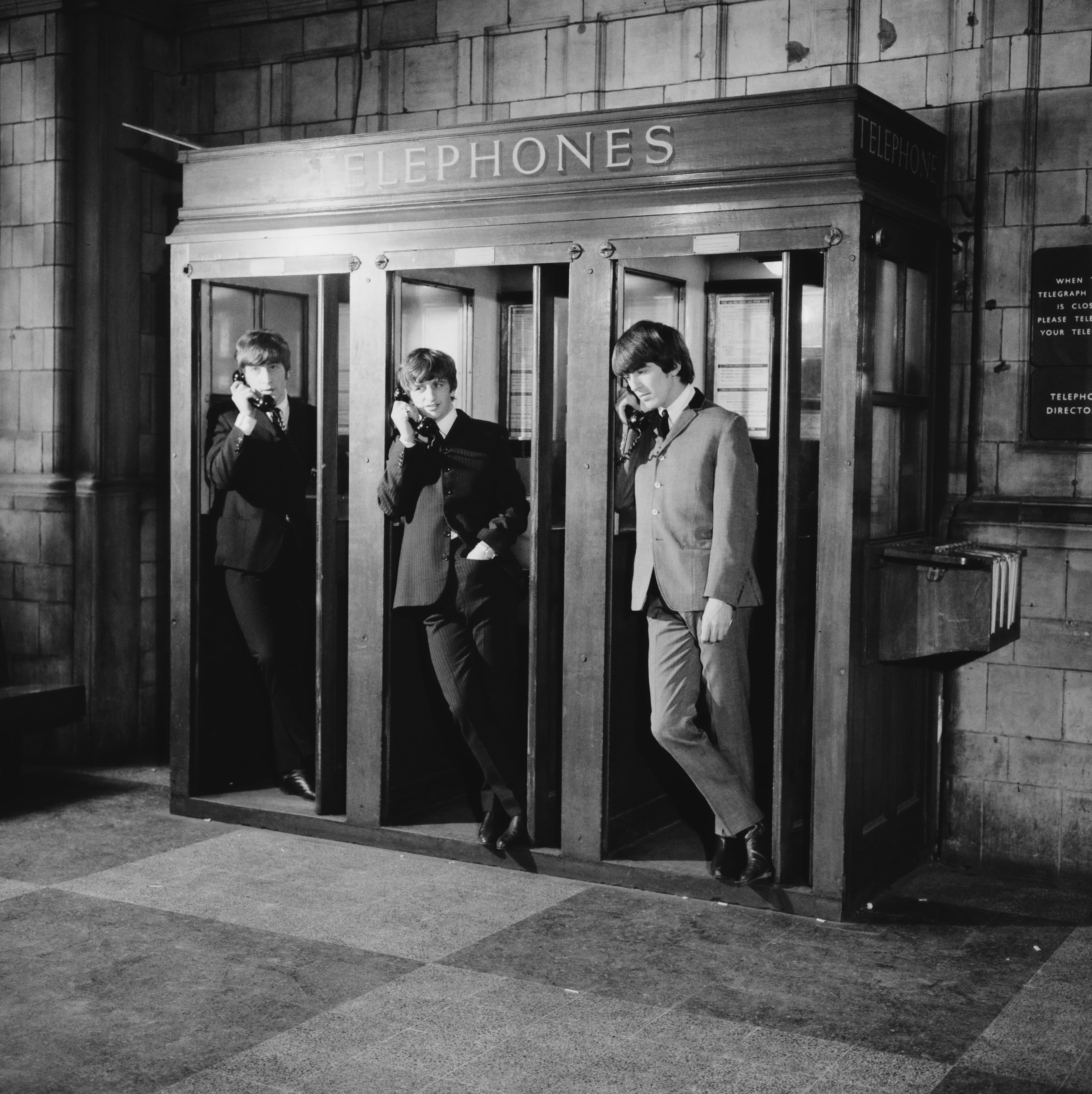

The Lennon that was being revered and revisited was the bearded peacenik of John and Yoko fame. Earlier incarnations, the cheeky, funny Beatle, the sometimes aggressive Beatle, the genuine wit who in 1964 and 1965 wrote and drew two now largely forgotten slim volumes of anarchic humour In His Own Write and A Spaniard in the Works had been somewhat written out of history. Even all these years later, one Lennon persona seems to out-shadow all the others in the communal memory. And that’s rather a pity.

But if Lennon’s death changed anything (and it certainly didn’t change America’s gun laws despite pleas from Beatles producer George Martin and others in the circle) it changed forever the status of The Beatles. In that post-punk year of 1980, the band wasn’t much mentioned or thought about, attempts to set up a Beatles museum in Liverpool had foundered. Liverpool Council, in its wisdom, had allowed the Cavern, where they had their early success, to be closed down and its basement filled in.

Lennon’s death brought home to everyone how much they missed him and missed the group. They were never to be out of the public eye again, certainly not out of the public memory and public affection. Fittingly, as we approach the anniversary of John’s death and wait to see if a new documentary really will shed any new light on anything, we have new Beatles music. A song with all four of them playing on it, written by Lennon and featuring his voice. Forty-three years after John’s death and 53 years after the band split, you couldn’t have made that up.

John Lennon: Murder Without A Trial is available now on Apple TV

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks