Jimi Hendrix and Handel's lives come together in exhibition of Mayfair flats they lived in 200 years apart

The guitarist claimed to see the ghost of the composer who lived next door 200 years before. Now his flat is open to the public and Kevin Legendre is among the first to take a look

London’s blue plaques stud the facades of buildings where historical game-changers once lived, but are increasingly easy to overlook as the city grows ever more dense with chain stores and luxury apartment blocks.

Yet behind two of of them is a a tantalising tale. Jimi Hendrix’s badge of honour is close by that of George Frideric Handel, who, in the 18th century, long before guitars were plugged in and amps cranked up, lived next door.

Fate, in its whimsy, separates a rock visionary from a classical icon by one wall and 200 years.

The first room visitors enter in the new exhibition that recreates in painstaking detail the flat that Hendrix shared with his girlfriend Kathy Etchingham in Brook Street, Mayfair, between July 1968 and March 1969, formerly served as Handel’s attic. It brings the presence of the mesmeric guitarist-vocalist’s illustrious neighbour into sharp focus.

Legend has it that one night Hendrix saw the composer’s ghost waltz through the brickwork, prompting the resident American to quaintly dub the revenant German “an old guy in a nightshirt and a grey pigtail”.

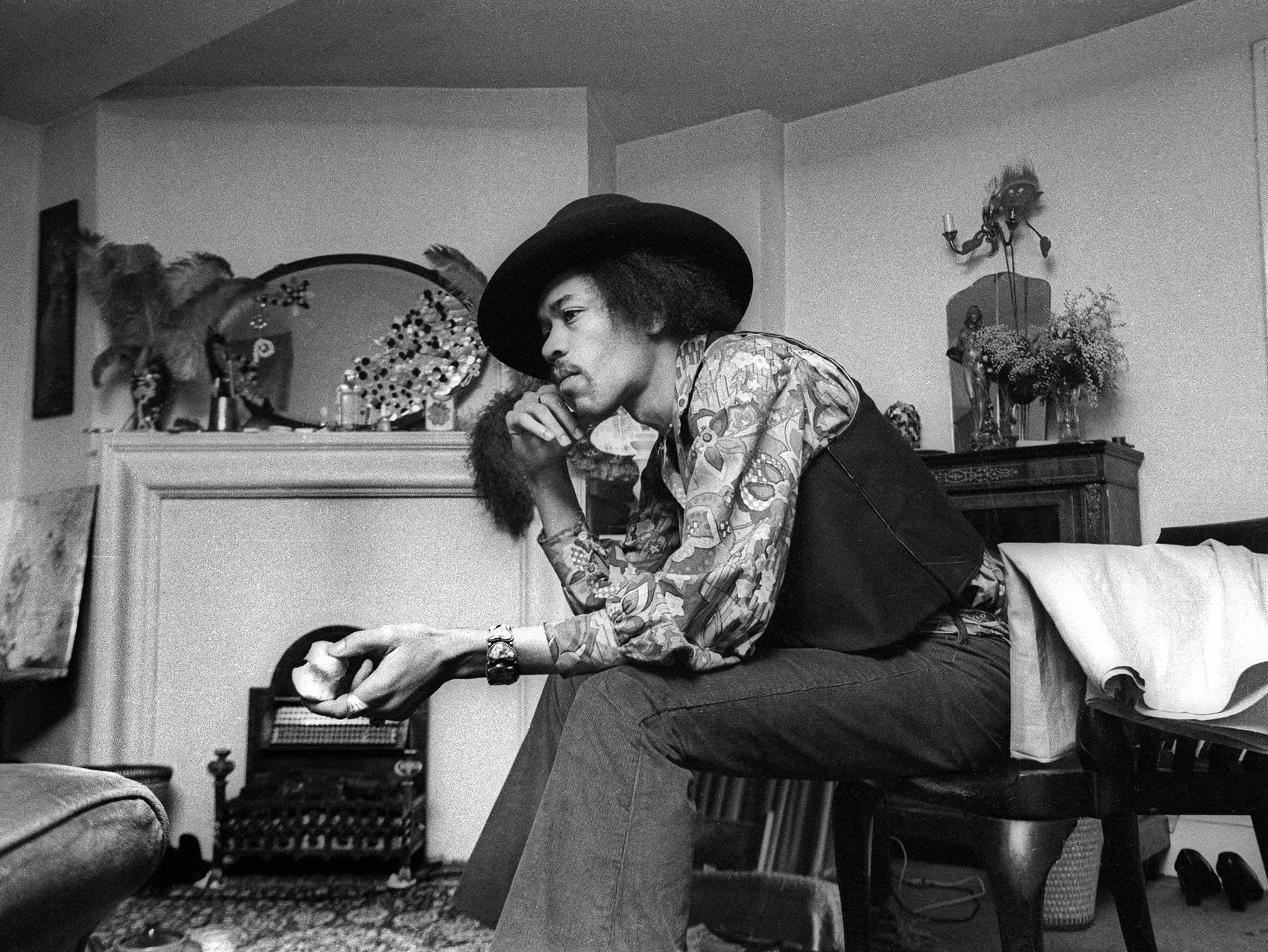

If that apparition was earnestly monochrome then the exhibition itself is lacking neither colour nor character. In its “facts zone”, which presents a useful synopsis of the artist’s career, Terence Donovan’s quite extraordinary portrait of Hendrix, swathed in enough eye-poppingly vibrant fabrics and beads to make him a Cherokee-Moroccan mosaic come to life, draws one’s attention as much as his Epiphone FT79 acoustic guitar, housed relic-like in a glass cabinet.

Hendrix’s innovations with technology, largely aided by pioneering engineer Roger Mayer, are highlighted, as is his engagement with Swinging London, where Carnaby Street gave him threads, the Speakeasy club gigs, and the Mr Love restaurant down on the ground floor of the building – he was up on the third – steak and chips.

Walk into Hendrix and Etchingham’s bedroom, with its array of textiles, rugs, wall hangings and an oval-shaped mirror festooned with feathers, and you see a sanctuary that reflects some of the flamboyance of the man who painted rainbows of sound on Electric Ladyland.

Yet the exhibition designer, Catherine Halcrow, was also keen to convey the prosaic side of Hendrix’s existence: “We wanted to give a sense of a real person rather than an icon. Brook Street was his first real home of his own.”

Indeed Hendrix’s hitherto unstable, gypsy-ish, life as a gigging musician in America makes the sight of oh-so-British paraphernalia such as curtains purchased from John Lewis, a box of Quality Street, a tea set and a television – he loved PG Tips and Coronation Street – charming.

But watching sitcoms didn’t stop Hendrix from playing guitar or hosting anybody from George Harrison to Eddy Grant or Richie Havens.

Equally fascinating is the former storage space next to the bedroom that is now used to display Hendrix’s treasured record collection, a road map to the ground-breaking destination of his own music. There is blues– Jimmy Reed, Elmore James, John Mayall. There is jazz – Wes Montgomery, Charles Lloyd, Django Reinhardt. There is pop and rock – Bob Dylan, Cream, the Bee Gees. And there is Indian and European classical music – Ravi Shankar, Holst, and Mr “nightshirt and grey pigtail”, Handel.

“The range of music is large,” says Christian Lloyd, the musicologist who was a researcher for the exhibition and the author of the accompanying book. “I think he saw music as a continuum. On “Up From the Skies” he said, ‘I want to see and hear everything’, and was true to that. He had encyclopedic knowledge. He once said about his clothing, ‘I love colours that clash’. Maybe that’s in the music too. He hated genres and the generic; he had a very open ear.”

Viewing the aforementioned discs pinned to a wall brings home to the visitor the disparate nature of the sources on which Hendrix drew.

But there are other more revealing details. Dylan records have the distinction of the highest number of scratches because Hendrix wore them out. And the albums of Dylan covers by Joan Baez and The Hollies were acquired for the purpose of studying the competition, so as to be able to put a different spin on his own reprise of songs by the man who changed the face of pop. Job done on “All Along the Watchtower.”

An interest in Dylan as well as a close friendship with Brian Jones kept Hendrix up to date with the pop world but his reverence for the great jazz soloists of the day, like Rahsaan Roland Kirk, whose imagination was so fertile he would play several horns simultaneously, would lead to more than just the purchase of their records.

Of all the numerous jams that took place at Brook Street, the most celebrated happened when Kirk swung by after playing at Ronnie Scott’s in nearby Soho.

While that session is held up as a crucial harbinger of Hendrix’s desire to stretch his aesthetic beyond the confines of rock, the records by classical composers that he slipped on to the state-of-the-art Bang & Olufsen turntable in the bedroom were also subjected to listening that was far from superficial, as Lloyd explains: “Visitors to the flat recall he’d play along to them. He played along on his guitar to Handel.”

This is borne out by the fact that Hendrix quoted Handel’s Messiah at his Winterland concerts in San Francisco in 1968, though it’s also worth noting that the guitarist pointedly declared that he “dug Bach”.

As much as the blues were deeply rooted in Hendrix’s musical life, they were not immovable. He was intent on branching out as much as his muse dictated, becoming a true audio adventurer willing to probe the timbral nuances of feedback, distortion and electronic noise as well as flout the norms of both the three-minute song and the three-piece band.

Interestingly, Vernon Reid, founder of subversive black rockers Living Colour, one of the key groups of the Eighties, has argued that Hendrix was a multifaceted persona, not to be reduced to simplistic definitions: “It was just one fluid thing – his songs; his playing; his whole vibe. People tend to get fixated on his playing, but the thing about Hendrix is he created the context for his playing to exist. That’s the real genius.”

The exhibition reinforces that, and with plans to turn Handel House Museum into Handel & Hendrix in London, complete with a performance and learning space that will feature “musical time travel” between the two men, there is a debate to be had on where they fit in a cultural hierarchy. What value to give a wah-wah rhythm and a lyric about a voodoo child as opposed to a score for strings and voices for a divine saviour? What value to give electric rather than acoustic music?

Hendrix’s desire to be taken seriously as an artist rather than an entertainer made him a complex, mercurial and challenging figure. But whether the world can see beyond a rock god and appreciate a sensitive, resolute, creative individual is perhaps a moot point.

On their respective blue plaques Hendrix is called a “guitarist and songwriter” whereas Handel is a “composer”. Make of these terms what you will.

The Hendrix Flat opens on 10 February (handel hendrix.org)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks