Burning Man: From far-out freak-fest to corporate schmoozing event

Begun in the 1980s as a celebration of counter-culture, Burning Man in Nevada has become a bragging event for networkers. Sophie Morris learns how it lost its spark

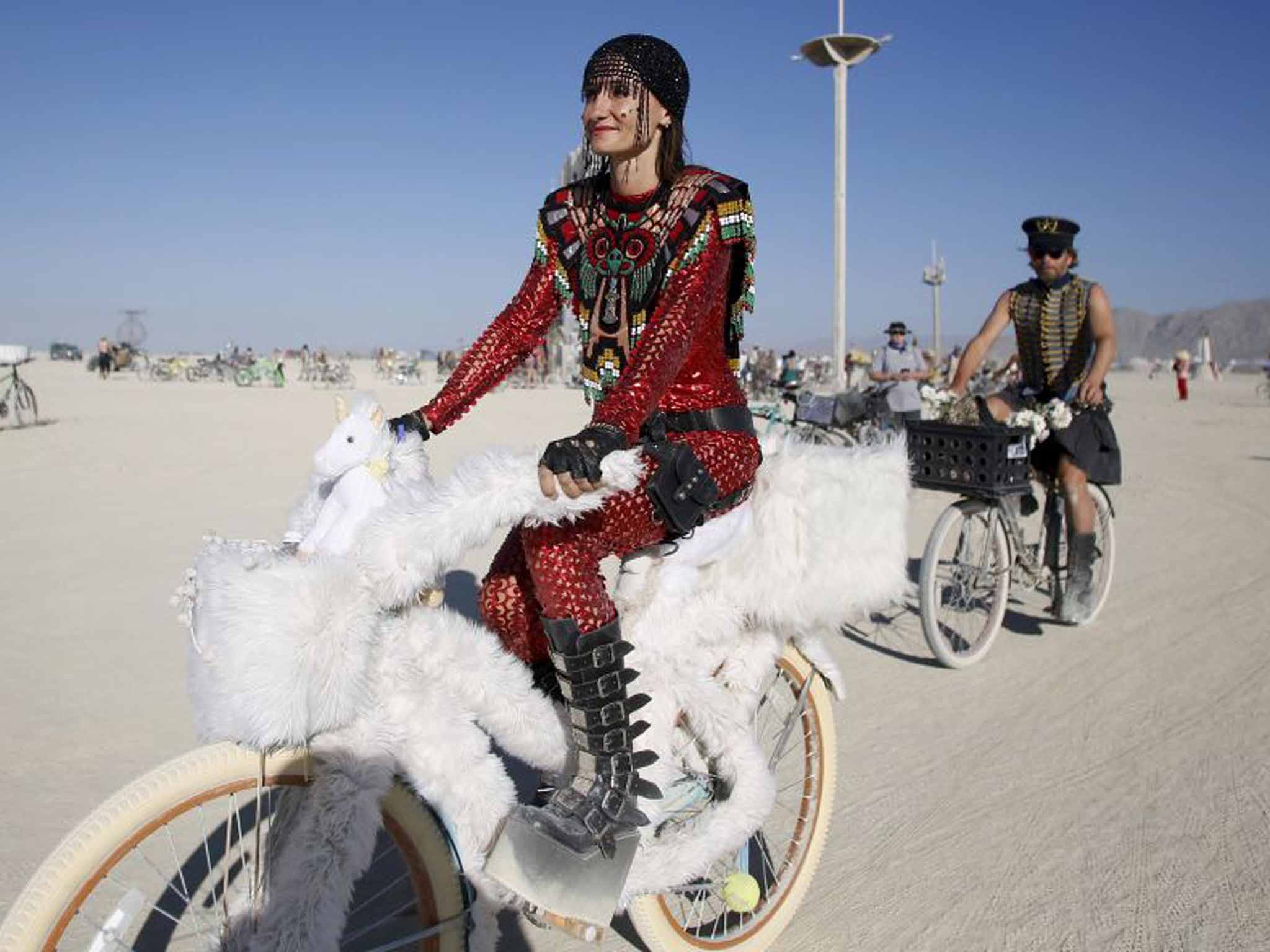

Utopia, a social experiment, an interactive arts festival (sorry, gathering) or a damn fine rave. Burning Man is known as many things. More than 70,000 acolytes of the annual week-long event gathered at its Nevada desert location over the weekend, lured by the promise of an alternative way of life, if only for the duration, as well as awe-inspiring art installations, great costumes, dance, music and wacky races.

This counter-culture approach, as the story of Burning Man goes, is built into its very ethos. But three decades on from the original burning, that counter-culture has grown and diversified, and it's almost as hard to maintain as the fine red sands of the Black Rock Desert, a few hours' drive north of Reno.

It began in 1986 when Larry Harvey and Jerry James knocked together a wooden wicker man-esque structure and took it down to San Francisco's Baker Beach, where they set it alight, attracting crowds and spontaneous displays of song and dance. "At the moment it was lit," Harvey recalled later, "everybody on that beach, north and south, came running. That beach was a little like the form of our city now, with its two embracing arms around the void of the playa here. And suddenly, our numbers tripled."

That "here" is today called Black Rock City, while on its website, Burning Man describes itself as "a temporary metropolis dedicated to community, art, self-expression, and self-reliance. In this crucible of creativity, all are welcome."

Except if, say, you wanted to hang out for a while at the pad of a wealthy businessman, but hadn't previously paid the $16,500 (£10,760) entry fee – last year, one venture capitalist asked 120 guests to pay this amount for entrance to his luxurious "turnkey camp", where models were reportedly flown in to "keep guests company". Although no money is exchanged at Burning Man, services can be paid for before and after, and exclusive "turnkey camps" (translation: civilians not welcome) are growing in number. This story made the headlines after Burning Man 2014, because it seemed to encapsulate the growing fears of thousands of dedicated participants who had been attending for years and watched its growth in popularity and profile. The developments in size and scale have been attended by subtle changes in the character of Black Rock City inhabitants and the character of the event as a whole.

News of this outrageously exclusive and bourgeois encampment, however, came as no surprise to large numbers of regulars. You don't even need to whisper it any more: Burning Man has developed a reputation as a networking event for well-connected Silicon Valley types looking for creative spaces to express themselves now that the office games room and ball pool have jumped the shark.

Google's founders, Sergey Brin and Larry Page, go there, Facebook's Mark Zuckerberg flew in for 24 hours last year, and Tesla's Elon Musk has said that Burning Man "is Silicon Valley", presumably suggesting that the radical live arts exhibition is a microcosm of the wonder spread through the world by San Francisco's tech scions.

On a certain level, Black Rock City has always existed somewhat uncomfortably, trapped between its stated socialist aim as a sharing and giving community (some friends of mine, naive to the harshities of desert life, turned up 15 years ago with a pop-up tent and a few litres of water, and had a warm welcome where they were fed, watered and sheltered from the sun for the whole week) and a nihilistic libertarian playground where the meek are trampled underfoot as the rich build bigger, taller and more elaborate offerings of "art" to the powerful event organisers. The comparisons with the Mad Max films, often drawn thanks to the creative carnival-meets-caveman outfits and hybrid sci-fi vehicles roaming the camp, gain meaning each year as the festival becomes less lovey-dovey and more edgy neo-liberal playground.

And the organisers, well, they welcome the patronage. Burning Man's director of business and communications, Marian Goodell, has even gone so far as to describe it as "a little bit like a corporate retreat. The event is a crucible, a pressure cooker and, by design, a place to think of new ideas or make new connections. Burning Man on the outside has very liberal and socially strong principles, but I've been running it with very fiscally conservative policies." I wonder how many people told their loved ones they were off to a fiscally conservative corporate retreat before heading off to Black Rock City this weekend.

There are also rumours of a permanent Burning Man space, as the founders are trying to buy a piece of land close to the festival's location to see whether their dream could work year-round.

Perhaps the critics are just jealous – after all, 60,000 people didn't manage to buy one of the $390 (£254) tickets this year. Meanwhile, reports of plagues of biting bugs infesting the site spread around the internet almost gleefully (the swarms have now apparently dispersed).

Besides, there's no need to worry if you couldn't get a ticket (or didn't fancy bumping into your lawyer while cycling naked across the desert). A few alternatives are emerging: Burning Nest in Wales, near Port Talbot, Midburn in Israel's Negev Desert, Burning Seed in New South Wales, Australia, and Nowhere in Catalonia all offer smaller, newer and much less networky locations to get your burn on.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks