When Yoko Ono joined The Beatles in the studio for the first time

The second volume of the first ever biography of Sir George Martin tells the factors that led to The Beatles producer’s withdrawal during the making of the White Album

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.On Thursday, 30 May 1968, George Martin and The Beatles finally reconvened in Studio 2 to work on their next, much-anticipated and as-of-yet untitled follow-up album to Sgt Pepper. They clearly planned to attack the new LP with a vengeance, having pre-booked Abbey Road studio time, every weekday from 2.30pm to midnight, through late July.

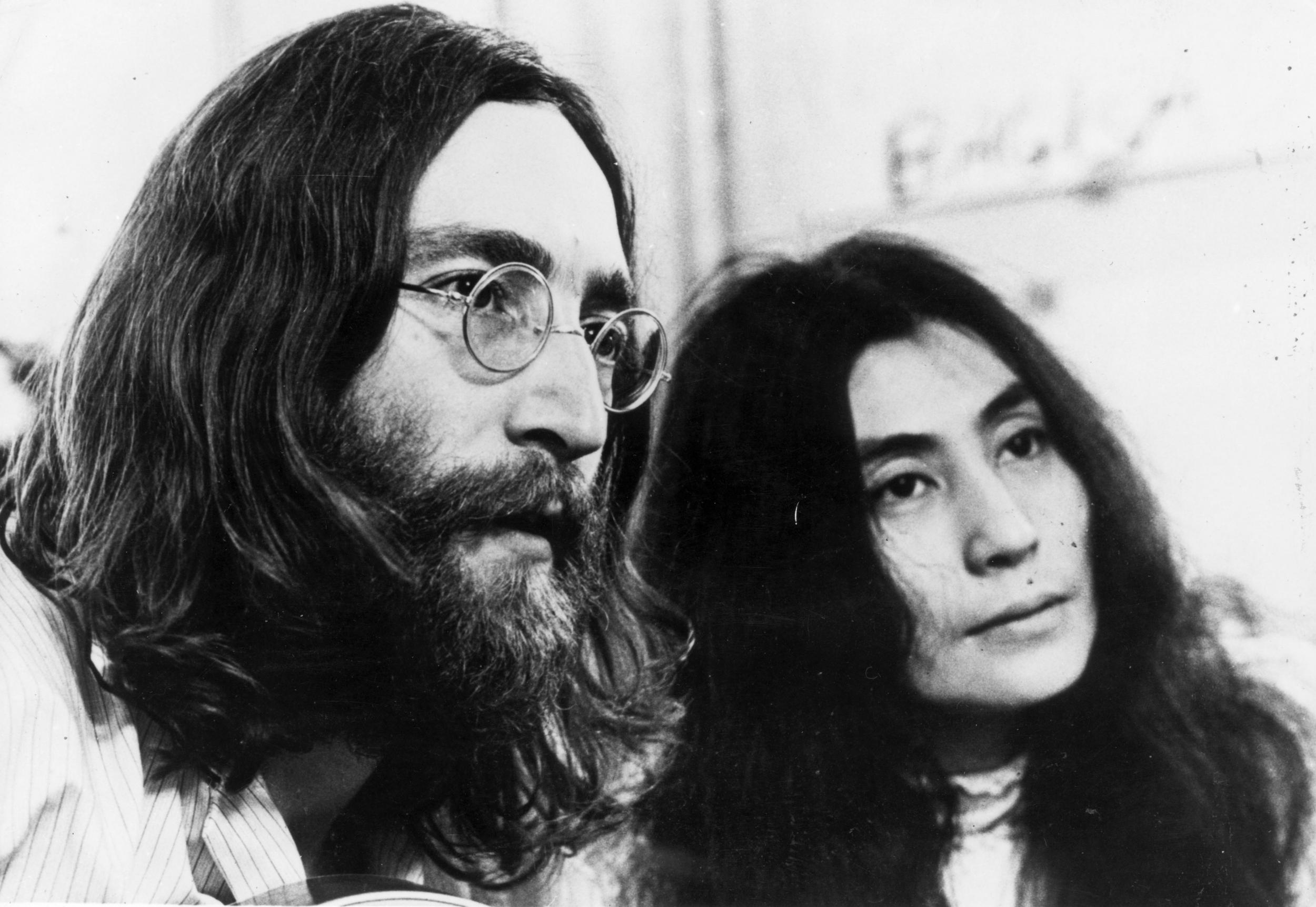

And while the bandmates were armed to the teeth with new compositions, pre-tested and demoed at Kinfauns only a few days earlier, they weren’t alone. They were joined by Yoko Ono, only this time things were decidedly different from the Japanese artist’s visit to Abbey Road during “The Fool on the Hill” sessions back in September. On 19 May – with Lennon’s wife Cynthia away on holiday in Greece – John Lennon had invited Ono to his Weybridge estate, where they stayed up all night improvising recordings on his Brenell reel-to-reel tape recorders as Ono shrieked a series of wordless, discordant vocals into the growing cacophony. At dawn, they consummated their new relationship.

A few days later, Cynthia returned from her Grecian holiday just in time to discover Ono wearing her bathrobe and sitting cross-legged on the floor of her Kenwood kitchen with Lennon. Cynthia’s marriage to Lennon had promptly fallen into shambles as the Beatle pondered a new life with Ono beyond Cynthia and his five-year-old son, Julian.

And now, Ono had insinuated herself into the lives of George Martin and The Beatles as well. The professional sanctum of the studio, which had long been the bandmates’ sanctuary from the ever-encroaching outside world, had suddenly been upended by Ono’s presence. With the exceptions of Sheila Bromberg’s harp work on “She’s Leaving Home” and the Mike Sammes Singers’ turn on “I Am the Walrus”, Martin and The Beatles’ collaboration had largely been a masculine one. They had each hailed, in their own ways, from Old World mores in which men and women followed highly gendered norms – Martin from working-class north London and The Beatles, who shared traditional northern upbringings. By drawing Ono into their workaday world, Lennon had turned their universe on its head.

It was Geoff Emerick who felt the winds of change first. When Lennon arrived at the studio that day, he deposited Ono in the control booth before shuttling into the studio. As Emerick later wrote, “For the next couple of hours Ono just sat quietly with us in the control room. It had to have been even more uncomfortable for her than it was for any of us. She had been put in an embarrassing situation, plunked right by the window so that George Martin and I had to crane our heads around her to see the others out in the studio and communicate with them. As a result, she kept thinking we were staring at her. She’d give us a polite, shy smile whenever she’d see us looking in her direction, but she never actually said anything.”

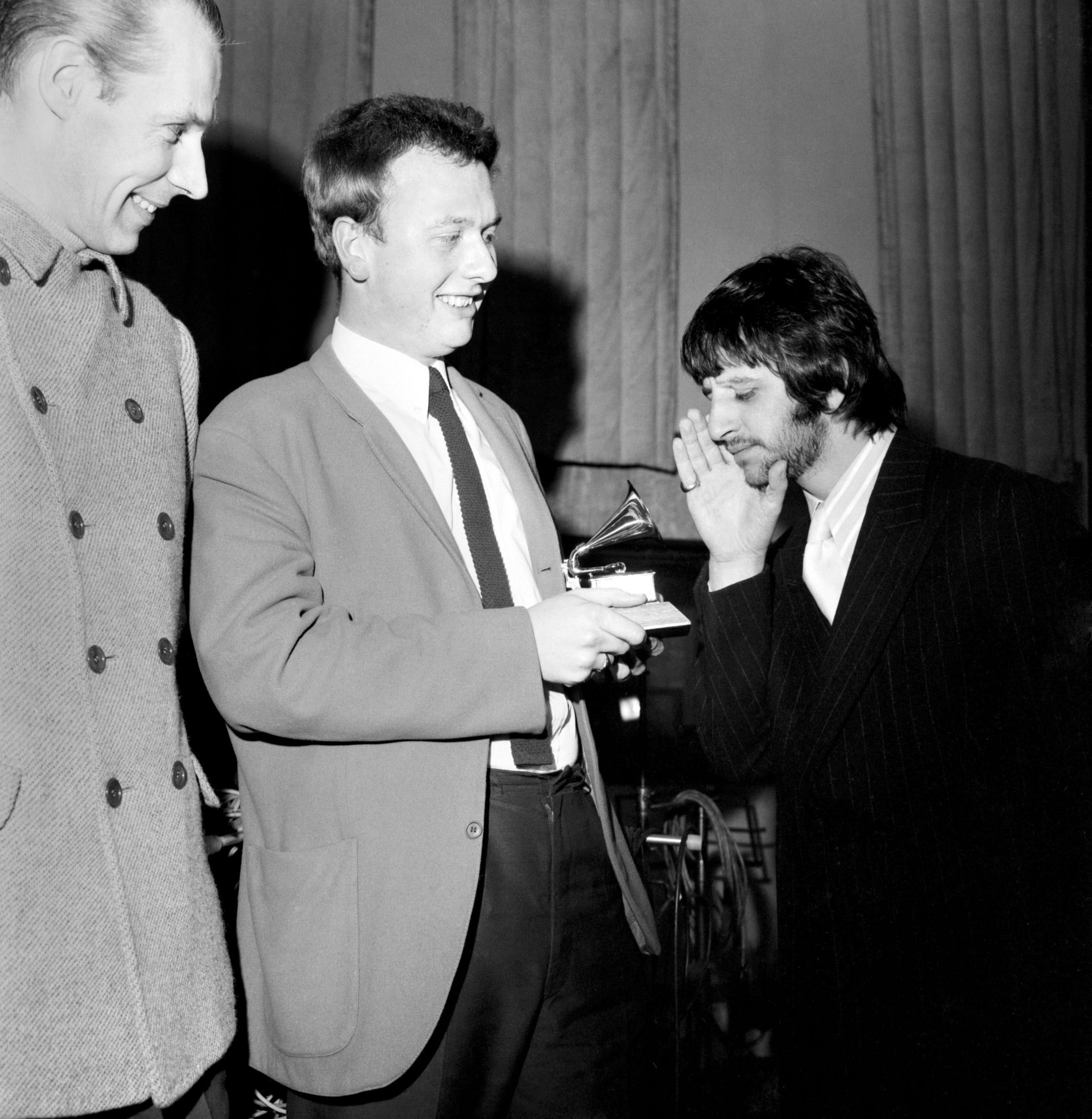

But Ono wasn’t the only new face in the control room that day. Martin had invited a guest of his own named Chris Thomas, the producer’s 21-year-old protégé from Air, who was learning the ropes of record production. Thomas had first caught Martin’s eye after he wrote a letter to The Beatles’ producer seeking work. In 1967, Martin had hired him as a production assistant at Air, and he had recently cut his teeth attending sessions at Abbey Road with Ron Richards and The Hollies.

As the session got underway on 30 May, Lennon debuted a new song that would come to be known as “Revolution 1”, a standout composition from the Esher demos. With Martin and a whole array of people up in the booth, The Beatles perfected a rhythm track in eighteen takes, including Lennon’s lead vocal, McCartney’s piano, Harrison’s acoustic guitar, and Starr’s drums. As the longest performance of “Revolution 1”, the eighteenth and best take clocked in at more than ten minutes. Emerick can be heard announcing “take 18” when the song rolls into being, with the bandmates eventually concluding “Revolution 1” with an extensive jam before Lennon shouts, “Okay, I’ve had enough!”

During the song’s final, chaotic six minutes, Lennon and Ono, who had succeeded in making her way down to the studio proper, dropped a series of non sequiturs into the sonic bedlam on 31 May. In addition to Lennon’s moaning and other non-verbal ministrations, Ono can be heard deadpanning “if you become naked”. While such random effects would be reserved for later deployment on the new album, Martin and The Beatles were forced to contend, in the short run, with the take’s gargantuan length, especially as they were already considering “Revolution 1” as a candidate for the next single. As for Ono, once she had cleared a path to her boyfriend working down in the studio, she would almost never leave his side.

But for Emerick, the session would be memorable for reasons well beyond the unexpected appearances of Ono and Thomas. As the session got underway, Emerick could tell that The Beatles were playing louder than ever before, with Lennon’s amp turned up to “an ear-splitting level”. As Martin looked on in silence, Emerick was especially concerned because of the sonic leakage from Lennon’s amp into the other microphones.

After politely suggesting that Lennon lower the volume so that he could adequately capture the recording, Emerick was stunned by The Beatles’ response over the talkback: “I’ve got something to say to you,” Lennon caustically replied. “It’s your job to control it, so just do your bloody job.” At that point, Martin and Emerick exchanged knowing glances. And that’s when The Beatles’ producer told Emerick: “I think you’d better go talk to him.”

Moments later, Emerick had joined Lennon down in the studio. “Look,” Lennon calmly explained. “The reason I’ve got my amp turned up so high is that I’m trying to distort the shit out of it. If you need me to turn it down, I will, but you have to do something to get my guitar to sound a lot more nasty. That’s what I’m after for this song.” As Emerick began to make his way back to the booth, already imagining a solution to Lennon’s dilemma, he was thunderstruck when the Beatle sneered, “Come on, get with it, Emerick. I think it’s about bloody time you got your act together.”

When Emerick returned to the booth, he was met by Martin, who asked, impassively, “What’s he on about?” But for his part, Emerick was speechless in the face of Lennon’s bluster. “I was so mad I couldn’t even answer,” the engineer later recalled. “After taking a few minutes to regain my composure, I decided to overload the mic preamp that was carrying Lennon’s guitar signal.” Emerick was essentially drawing on the same remedy that had been devised to afford Lennon’s voice with additional texture during the sessions devoted to “I Am the Walrus”.

As the “Revolution 1” session progressed, with Lennon’s guitar resonance having been rendered to his liking, Emerick had become transfixed by the evening’s unsettling ambience. “That first night’s session was uncontrolled chaos, pure and simple,” he wrote, “and George Martin had looked puzzled and concerned from start to finish. He and I knew that something was not quite right here.”

For his part, Martin had also registered the difference in The Beatles’ atmosphere, and he strategically fell back on the calculated approach that had served him well in previous years. He self-consciously enacted a “tactical withdrawal”, just as he had done during the production of the Help! long-player and, more recently, during the post-Pepper era. To his mind, this approach allowed him to be available as a resource for The Beatles while carefully navigating his way among their understandably towering egos after years of unparalleled success. But in the ensuing days and weeks, he began adopting a different guise in the studio, arriving early, as he had always done, but purposefully carrying a thick stack of daily London newspaper. Outfitted in this fashion, he would recline in the control booth, occupying his mind until he was needed. Withdrawn and catching up on the news of the world, to be sure, but also eminently ready to answer The Beatles’ every beck and call.

This is an excerpt from Sound Pictures: The Life of Beatles Producer George Martin (The Later Years: 1966-2016) by Kenneth Womack, published by Orphans Publishing, on 4 September

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments