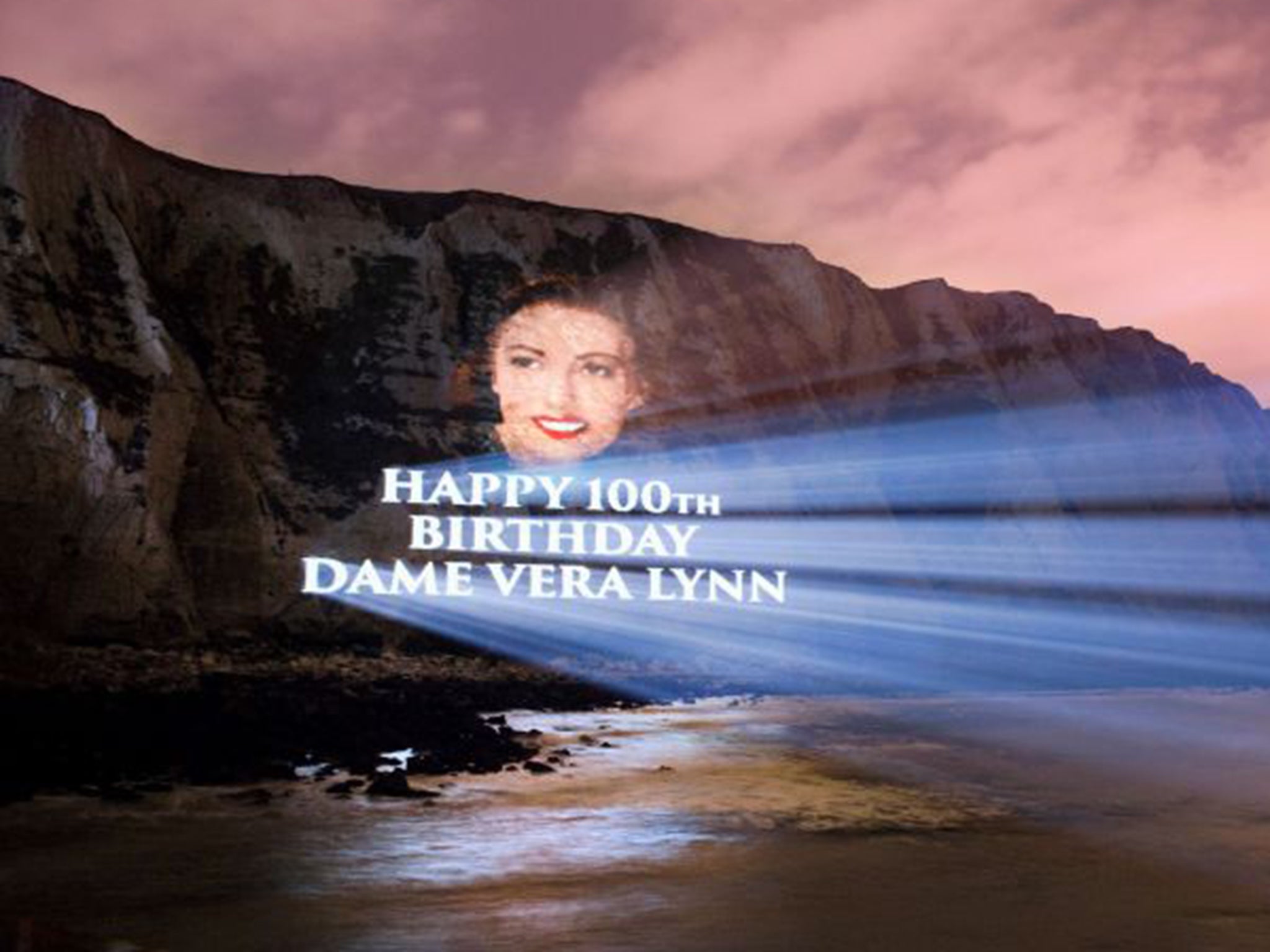

'We'll Meet Again': Dame Vera Lynn turns 100 nearly 75 years after VE Day

Singer is celebrating her 100th birthday

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It was the 50th anniversary of the allied victory in Europe, V-E Day, and the old ones gathered in London’s Hyde Park to remember, many of them in wheelchairs or leaning on canes.

Others paraded in slowly, to old marches played at a gentler tempo: veterans of the armed forces and fire brigades; former air raid wardens and nurses; the few survivors of the Women’s Royal Voluntary Service, once a million strong.

The strains of Vera Lynn singing ‘We’ll Meet Again’ wafted through the park. ‘We’ll meet again. Don’t know where. Don’t know when,’ and it brought a smile to many an ancient face, and a tear to others, and sometimes both.

Many knew that for them, "this is the last time," as former Royal Marine Boyland Henry, 78, said.

That was May 7, 1995. And for most of those gathered there that day, it no doubt was “the last time".

But not, remarkably, for Vera Lynn.

On Monday, she celebrates her 100th birthday. And she’s celebrating by releasing an album, “Vera Lynn 100,” reorchestrating her most famous songs, along with their originals, just as she did in 2014, at the age of 97, when the release of a new collection of her songs made her the oldest living artist to get a top 20 album in the United Kingdom, if not anywhere.

It too featured “We’ll Meet Again” and “(There’ll be Bluebirds Over) The White Cliffs of Dover.”

The British remain captivated by World War II, much more so than Americans, no doubt because it was so close to home, indeed, for a time, during the bombing of Britain, it was at home. And Vera Lynn, like Winston Churchill before her, is one of the last universal symbols of that time, Britain’s “finest hour,” her songs an instant jog to a distant memory.

To fully fathom the meaning of Vera Lynn to the British, you have to picture a British soldier, in the depths of Britain’s despair at the outset of World War II, hunkered down somewhere in North Africa, wondering how, if ever, it would end and whether, if ever, he’d get home.

“We were very lucky,” said one such soldier, William Pitcher, in a 1996 oral history. “All the war, even the worst of times, we had a good short wave radio system. In fact, I can remember it was desert, we’d, in the nighttime, on Saturday nights when Vera Lynn come on we’d get the radio off the truck and we’d cover ourselves up with tarp and turn it on. And we’d listen to Vera sing to the troops on a Friday night, on the radio.”

The song itself was “unabashedly sentimental” writes Christina L. Baade in her book, “Victory Through Harmony,” with it’s “romantic longing and an insistent faith in the couple’s eventual reunion.”

We’ll meet again

Don’t know where

Don’t know when

But I know we’ll meet again some sunny day

Keep smiling through

Just like you always do

‘Till the blue skies drive the dark clouds far away

So will you please say hello

To the folks that I know

Tell them I won’t be long

They’ll be happy to know

That as you saw me go

I was singing this song

We’ll meet again

Don’t know where

Don’t know when

But I know we’ll meet again some sunny day

“It’s a good song,” Vera Lynn said simply at the time. “It goes with anyone anywhere saying goodbye to someone.”

But there was also something about Vera Lynn, a child of London’s working-class East End, the daughter of a plumber, someone the average soldier could identify with, a literal girl next door.

Lynn, in a 1999 interview with the BBC, recalled the day Britain went to war.

“We were in the garden, my mother and father and myself. … We were there having tea and saying happy birthday and all that, but at the same time we had the radio on, listening and waiting for any news to come through. One was expecting it but it still came as a bit of a shock. … I’d been broadcasting for a few years,” she said, and “was beginning to become quite well-known here in England.

“The first thing I thought of was ‘Oh well, bang goes my career. … I shall be either in the army or in a factory, doing something like that,’” she said.

“The thought that entertainment was going to be such a vital means of keeping people’s morale up, well I never thought about that at all at the time. Everybody had to sign on. I went and signed on expecting to go into the army or do something in the services. I was ready to do whatever they wanted me to do, like everybody else.

“But I was told, ‘No, you will be much more useful if you carry on entertaining,’” she said.

And so a living symbol of Britain’s war effort, and of the ineffable personal sadness, was born. She was “the forces favourite” as Baade wrote in the Conversation, “the ordinary East End girl with an extraordinary voice, whose broadcast over the BBC sustained the nation through the darkest days of the war.”

Oddly, in hindsight, her wartime radio show, called “Sincerely Yours — Vera Lynn,” while popular with ordinary people both on the front and the home front, fell afoul of the British brass, who worried that songs like “We’ll Meet Again” were too “slushy” for an army at war, particularly, at that time, a war going badly.

The show “became a target for criticism,” Baade writes: "An influential minority blamed the BBC’s “sickly and maudlin programmes” for significant British losses in North Africa and Southeast Asia.

"Sentimental popular music, they argued, had a “drugging effect” on the troops and undermined their masculinity and will to fight. Just because Lynn was the “Forces’ Favourite” did not mean she was actually good for their morale.

"To help calm this criticism, the BBC’s leadership decided to “rest” Sincerely Yours. Lynn, whose career was flourishing, still broadcast, but it was 18 months before she had another solo series."

By 1944, she was entertaining troops in person, singing at a camp in Burma not far from where a battle raged against the Japanese.

“She was like an angel to us,” veteran Roy Welland said in a recent interview with the Coconuts Yangon website. “I was quite lucky. I got a space at the show, almost at the front. I stood there and thought of home instantly.”

“‘C’ Company 7th Worcestershire Regiment and the rest of the men of the 4th Brigade were divided in their opinion of her voice,” recalled veteran Frederick Weedman of her performance in Burma, “but not after that hot steamy evening in 1944 in the Burmese jungle, when we stood in our hundreds and watched a tall, fair haired girl walk on to a makeshift stage and stand beside an old piano.

“She tried to leave the stage,” he recalled to the Coconuts Yangon, “but the men were clapping and cheering. She sang three more songs but still they went on cheering. She started to sing again but whenever she tried to stop, they yelled the name of another tune. She sang until her make-up was running in dark furrows down her cheeks, until her dress was wet with sweat, until her voice had become a croak.”

Vera Lynn would go abroad one more time the day after peace in Europe was declared.

“They phoned me up and sent me to Germany,” she told the Telegraph in a 2014 interview, to sing for the troops who had liberated the concentration camps. “They took me around the ovens. I saw the gas chambers. They were like a row of garages with steel doors. No birds were flying. They said the gas was still in the air.”

“When they write about the war, will they include me in it?” she asked as the Telegraph interview came to an end. Of course, she acknowledged with a smile.

“Well, that is lovely. I didn’t set out to be anything like that … People used me, in a way, to achieve something, and I was glad of it. I was just doing my job.”

Copyright: Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments