The Invisible Band at 20: Travis on the album that almost finished them

They were the oft-derided faces of the Noughties acoustic movement but there’s more to the Scottish group than Fran Healy’s mohawk. As their last big album turns 20, they talk candidly to Craig McLean about wrestling with fame, misfortune – and Coldplay stealing their thunder

When they think back two decades to the album that made them one of the biggest British bands in the world, half of Travis have separate but equally ticklish recollections of their “Peak Travis” moments. For guitarist and singer Fran Healy it might be getting A-lister urine on his feet at the “obligatory” Los Angeles party in 2000.

“It was in celebration of Alanis Morissette at some place in the Hollywood Hills and it was like a moving Madame Tussaud’s of celebrity,” remembers the Scottish four piece’s frontman. “My overriding memory is being absolutely desperate for a pee and there was a big queue for the three toilets. So I pissed in the garden. And Moby comes up and starts peeing beside me, and having a chat, as men do, while we’re splashing on our feet.”

Or it was the singer’s daily wake-up call from the pet pooch of the Hollywood lifer who was his neighbour in his Sunset Boulevard hotel. “I had Drew Barrymore living next door to me, with her wee dog. Every morning he’d be sitting outside my doorstep, waiting for me to play with him.”

For bass player Dougie Payne, the biggest pinch-me moments were meeting his idol David Bowie not once, not twice, but three times: at the 2002 GQ Awards, where they won Band of the Year; at JFK airport in New York, where he almost missed an all-dressed-in-beige Bowie; and backstage at a Bowie show at Wembley Arena in 2003, where the Dame discussed playing “The Laughing Gnome” at his imminent Glasgow show. “They’d like that, the Glassblowers,” mimics Payne in a thigh-slappingly excellent Thin White Duke impersonation. “Is that what they call you lot, Glassblowers? No, Glasgowers?”

Good times, for sure, for the Glaswegians. Which is all the more ironic given that they were happening to a group who, by design and title, proclaimed their disinterest in the fame hoopla that clustered around guitar bands of every stripe at the turn of the millennium. This was summer 20 years ago, when the Britpop party clatter had faded, New York’s skinny-tie-and-skinny-jeans gunslingers were limbering up for a small-scale garage-rock revolution, and the stadium-sized lasers of Coldplay and their breakthrough second album A Rush of Blood to the Head were 14 months away.

In the middle of all that, on 11 June 2001, Travis released The Invisible Band. Talk about a quiet storm. The follow-up to 1999’s accidental blockbuster The Man Who (which sold 3.5 million physical copies and won them British Group and British Album of the Year at the 2000 Brit Awards), their third album was another collection of plangent, ultra-melodic, quasi-acoustic pop – albeit tricked out with some interesting sonic flourishes courtesy of producer Nigel Godrich, then fresh (ie knackered) from the gruelling 16-month recording sessions with Radiohead that would produce both Kid A and Amnesiac.

You might say the album’s title shouted Travis‘s reserve, and Payne wouldn’t necessarily disagree with you.

“I understood why people got fed up with that, ’cause that ‘invisible band’ attitude is a little bit earnest,” acknowledges the musician over tea in the kitchen of his home in Glasgow’s leafy West End. “But it was genuinely how we felt. We weren’t celebrity or tabloid types. We were just doing our own little thing, working on our songs. That’s what we were good at. We weren’t good at being celebrities.”

We weren’t good at being celebrities

Unluckily for them, then, The Invisible Band entered the UK album charts at Number One. It sat there for four weeks, selling more copies in that time than The Man Who – home to the deathless “Why Does It Always Rain On Me?” – did in half a year. In 2002 Travis again won a Brit Award for British Group of the Year.

Ten years after Healy, Payne, Andy Dunlop (guitars) and Neil Primrose (drums) had got together in Glasgow, Travis were now huge. But it came with a cost. After chasing the runaway, unexpected success of The Man Who over some 18 months’ international touring, the band had one whole day off. Then they immediately began recording with Godrich in LA’s Ocean Way studios, relying on adrenaline and youth to keep them making and playing music for another solid year.

“And that was the point where Fran started to feel the pressure of this enforced celebrity. The Invisible Band, ironically, was the thing that made him very visible. With the Hoxton Fin and all that,” Payne says, referencing Healy’s much-copied bijou mohawk hairstyle, “suddenly he was everywhere. He became a face. People breaking into his house and stealing his fireplaces when we were away on tour and all that.”

Then, in July 2002, a record that began with a bang ended with a crack. Relaxing before yet another festival appearance, Neil Primrose – fried by, at that time, six years of album-tour-album-tour cycle – dived into a swimming pool in France. He knocked himself unconscious. Unbeknownst to the Travis road crew who pulled him out and applied mouth-to-mouth resuscitation – and to Payne, who travelled with the drummer in the ambulance to hospital – he’d also broken his neck.

Miraculously he recovered, not only without any paralysis but also to drum another day. But a road-weary Travis took the hint and went home. They would never be as big again. Within another year, Coldplay had taken the Travis template and supersized it. Even as the Scotsmen celebrate a bells-and-whistles 20th anniversary repackage of The Invisible Band this month, Healy insists he couldn’t have been less bothered at the spotlight moving elsewhere. For a man who likes his analogies, his friend’s near-death experience was a warning klaxon.

“Some airplanes can fly really, really high because they’re built for high altitude,” the songwriter reflects as he Zooms in from the driver’s seat of his car, parked outside the Los Angeles home that’s within peeing distance of that Morissette party. “And some planes, s*** starts to fly off them and you start to lose consciousness because the pressure’s too high. And what happened to Neil saved us, actually. It brought us down.”

Scant 24-hour micro-break or not, going into the making of The Invisible Band in November 2000, Travis were pumped up and ready to soft-rock. After all, they’d been touring solidly for four years, since well before the release of 1997 debut Good Feeling.

“We spent two years supporting everybody,” remembers Payne, 49, of the period after the four friends, who got together in the social circles surrounding Glasgow School of Art, moved to London in 1996. “Mansun, Cast, Longpigs, Paul Weller, Oasis. Just going round and round the country, up and down and up and down.”

Then came the world tour in support of global hit The Man Who.

“We had played so much, done this massive tour, that we were playing brilliantly together, at the top of our game,” says Healy, 48. “We’d done between 400 and 500 shows since ’96, so it was an upward curve. We were ready for the Olympics.”

Going straight into the studio, then, was practical. “And when you’re in the turbine of that moment of your career, it was fine. None of us batted an eyelid. And it wasn’t like we were staying in a s*** hotel, putting up with cockroaches running up your kilt! We were in the Chateau Marmont, one of the best hotels ever!”

Plus, forearmed is forewarned: Healy was prolific and feeling good, having already written songs that, even in demo form, sounded like winners: “Sing”, “Side”, “Flowers In The Window”, future big singles all. He only needed three more songs to round out the album, which he duly wrote in a second LA session early in 2001: “Dear Diary”, “Follow The Light” and “Last Train”.

“But, still, getting those last three songs was difficult,” Healy admits, recalling pressure from their label boss and A&R man Andy MacDonald. “He was constantly pushing for singles, which was a slight bugbear of mine. Can I not just try and write a song? It’s like asking a woman to have a baby and make it have blonde hair and blue eyes. I just can’t do that. So you have to have loads of babies, and maybe one of them will have that. And that’s kinda what I did.

“But I was very confident,” the band’s chief songwriter continues. “I knew ‘Sing’ was the big hit, but there was a very passionate debate between Andy and me about what the first single would be. He was very, very into ‘Side’ as being That Song. I thought it was awright, but it didn’t have, in my opinion, the universality that ‘Sing’ had. That was almost like a calling card, like: this is what being in a band is. It’s like [the statement contained in] ‘Thank You for the Music’ by ABBA.”

Still, there were tensions with Godrich. With Kid A only released the previous month, and with Radiohead submitting to barely any interviews, the wider world were largely unaware just how gruelling the sessions for the fourth album had been.

“We were working with him after he’d spent all that time with Radiohead,” says Healy. “He came in and he was in a right mood. Really pissed off and angry – he was going through something. And because we’re the way we are” – that is, nice – “he took it out on us. Because he couldn’t take it out on Radiohead. His relationship with Thom [Yorke] is completely different from ours. Nigel and I are like brothers. Him and Thom, they fight over things. Not fisticuffs, but it’s quite a push-and-pull relationship – especially on that record.

“So he came to our session with a real cloud over him.”

Healy’s diary entries from the time reflect the turbulent mood: “Nigel thinks we’re s***. I think we are s***.”

Reflecting now, the singer – one of the most mild-mannered men in music – points out that “it’s not really good if the producer of your follow-up record is making you feel s*** rather than that you’re the biggest band in the world.”

All the new songs had been road tested during soundchecks on The Man Who tour. But according to Payne, when Travis played them for their producer in the studio, “they were all just getting rejected. Nigel wanted to strip everything back. It was quite soul-destroying for a while. At the end of the first week, Fran and I were sitting in a car-park at Ocean Way with our heads in our hands: ‘He hates us, he hates the songs, we’re not going to be able to make this record.’ We were thinking he was gonna bail. It was a nightmare.”

But what Healy describes as “massive argument” cleared the air, while Payne cites the purchasing of “a whole load of weird instruments, like little beatboxes and drum machines and an electronic tanpura” as being pivotal as changing the atmosphere.

“We had those, and incense, and it all got a bit experimental,” smiles the bass player. “That’s when Nigel started getting engaged again and we all cheered up. We started having a good time, socialising in the Bar Marmont at the hotel with Jason Falkner from Jellyfish and the Remy Zero guys. And that good time started getting reflected in the studio.”

The result, thinks Healy, “is one of the best-sounding records we’ve ever made.

“With Radiohead,” he continues, “Nigel makes a certain kind of music, which is all, em… very Radiohead-y. But with us, he was working with a band that wrote very melodic songs. I always thought it was great that he had both of those types of bands to work with. He could do all the weird stuff with Radiohead but use all his supreme skill as engineer and producer on a band like us.”

The Invisible Band’s instant UK success didn’t have much impact on Healy. The singer’s focus was elsewhere, in the country in which he’d end up living 15-odd years later – after a long spell in Berlin – with his partner and son, now 15.

“All I wanted to do was break America. That was the objective, much to the annoyance of your record company in the UK – the first shows we did for the album were in America, we made the videos for ‘Sing’ and ‘Side’ there, with [Jonathan] Dayton and [Valerie] Faris, who went on to make ‘Little Miss Sunshine’.”

All I wanted to do was break America

Helping his ambition was the fact that the internet was just becoming a “thing” for artists. “We were one of the first bands to have a website – and we were the first band to put a web camera in the studio. While we were recording The Invisible Band we were letting fans see a picture every 30 seconds. We were talking with fans in chat rooms and message boards all the time.”

Unfortunately, their US label at the time was Epic, “and they really didn’t know what to do with us”, he claims. The company released and began promoting “Sing”. But after four weeks, an influential radio DJ in, Healy thinks, Philadelphia decided he preferred “Side”, and started playing that. As Healy tells it, the label “bottled it” and started pushing “Side” as the lead single, without telling the band.

“It’s like turning an oil tanker when you do that. Then a week after that, KROQ in Los Angeles, which was the biggest station, started playing ‘Sing’. But by that time everywhere else was on ‘Side’. Then 9/11 happened, and we were f***ed [in America].” That is: shows were cancelled, promotion was curtailed and singalong rock – no matter how acoustic and emotional – was the last thing on anyone’s mind.

Still, the album sold heavily everywhere else in the world, dragging the band on a seemingly never-ending tour that took in Europe, South America, Asia, Australia and New Zealand. Making a mockery of its own title, The Invisible Band made Healy in particular recognisable everywhere he went. Even if a lot of fans seemed to think he actually was called Travis.

“Getting famous is like growing horns, something visible to others that you can’t see,” he reflects. “You’ve not changed, but I remember walking down the street and hearing the ‘s’ of ‘Travis’ a lot – ‘that’s Travis!’”

The band’s ubiquity also became an issue. The September 2001 issue of style magazine The Face gave away enamel lapel badges. One of them read: “I Hate Travis”. Full disclosure: I was deputy editor at the magazine at the time. It was a playful – or you could say snarky – comment on Travis’s crushing dominance of the airwaves. (Full disclosure #2: myself and the editor didn’t really hate Travis, but we thought it wasn’t cool to admit that.)

Healy understands the sentiment – so much so that he wore the badge for the rest of The Invisible Band tour. Payne sympathises, too: “You know what, I get it. When you are everywhere, and on Top of the Tops all the time and Later… with Jools Holland 15 times, I understand it. People get sick of you. And that’s OK. You become a target, and that’s how it goes.”

There were other pressures, too. Six weeks after the release of The Invisible Band, The Strokes released Is This It. In the view of certain quarters, notably the NME and “proper” indie fans, this was the guitar-slinging American cavalry to the rescue, leading a charge that also featured The White Stripes, Yeah Yeah Yeahs, Interpol and, eventually, The Killers. They were here to deliver us from, in Alan McGee’s memorable phrase, the “bedwetters” of Coldplay, Athlete, Starsailor and, yes, Travis.

The perception that those Yank arrivistes were here to save rock’n’roll from the insipid Brits – how did that impact on Healy?

“The funny thing is that Travis and The Strokes are very similar types of bands,” he replies. “We were both ushers. They ushered in that whole ‘The’ type of band. We ushered in that acoustic thing. There was no one like The Strokes, and there was no one like Travis!”

In fact, he says, Is This It stayed on his in-car five-CD changer for 18 months, a period in which Travis and The Strokes became friends and mutually respectful peers. “I still love The Strokes.”

But he insists there was no frustration that The Strokes changed the conversation about what a guitar band could be. “Absolutely not! You guys talk about ‘the conversation,’” he states, meaning: journalists. “Music’s not about the conversation. It’s all about songs, and about entertaining people. So there was no frustration. The Strokes were a breath of fresh air. I was as big a fan of them as everyone else was.”

Music’s not about the conversation. It’s all about songs, and about entertaining people

Much more difficult for Healy was the constant talking about himself and the band. “One time we were in Paris doing promotion, from nine in the morning till eight in the evening, non-stop. And I remember asking the record company, can I not sit on the pavement for a minute? It was the first moment I’d had to myself in months. There was a sense of no escape. Your diary was full, days, weekends, everything, for nine months. That’s overwhelming.”

He was aware that Payne was also struggling. The bass player was in a new relationship with Trainspotting actor Kelly Macdonald, whom he’d marry in 2003 and have two sons with (they separated in 2017). But their time together, no doubt further complicated by her busy filming career, was at a premium. “So Dougie was suffering a lot, too. Then, in November we had this big conference with the management in someone’s hotel room in Madrid. Dougie said: ‘I just can’t do this anymore.’ The volume of work was taking its toll on all of us.’ I was like: ‘We have to keep going.’ I was still determined to smash America. But we just had to stop.”

The band scattered to their family homes. Healy remembers being home around Christmas time with his mum, the single parent who’d raised him, an only child. To his horror, he realised he was talking to her like she was interviewing him. “I had a total breakdown, crying my eyes out. But that was good. After that, the air was cleared again.”

After a festive break, Travis decided to do a handful of shows in spring and summer 2002. The offers were too good to turn down: a big show in Iceland, some plum European festival appearances and, as a final victory lap, headlining the main stages at the V Festivals in Chelmsford and South Staffordshire.

Then, in early July, as the band relaxed before playing the Eurockéennes festival in Belfort, northeastern France, Neil Primrose had his near-death swimming pool accident. It was almost exactly 11 months since the release of The Invisible Band and there was considerable life in the album yet. But for Travis, all bets were off. “Neil’s recovery was incredible,” marvels Payne. “Within six months we were in the studio in Crear in the [Scottish] Highlands recording [fourth album] 12 Memories.”

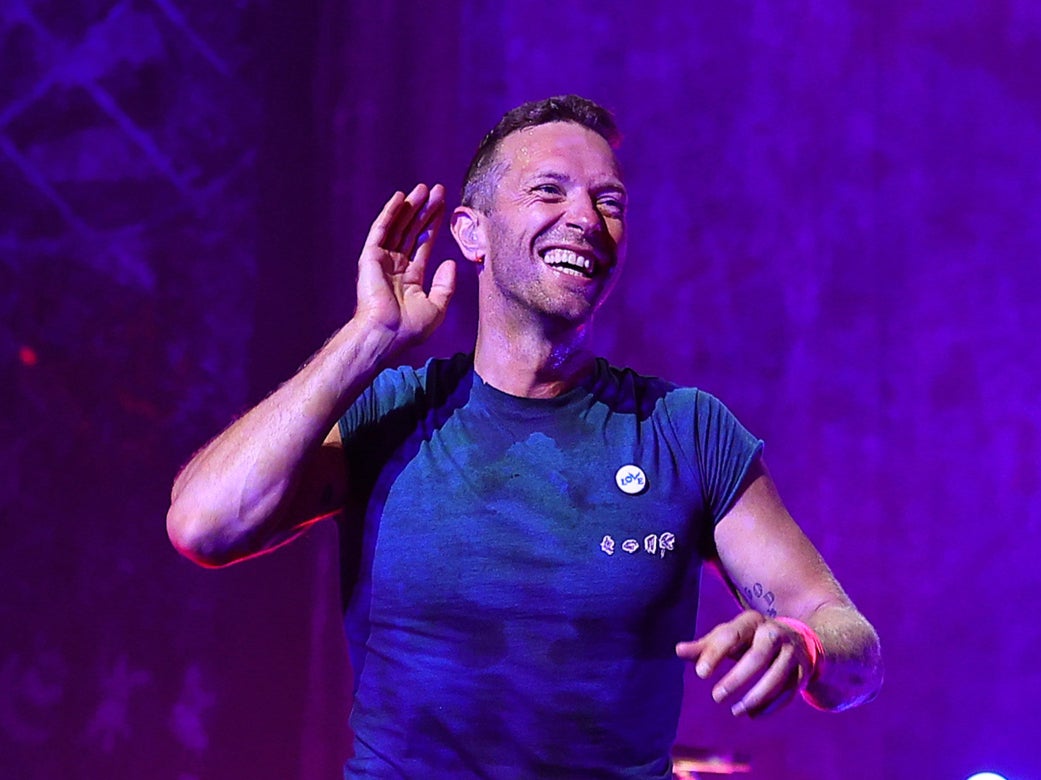

Fran Healy certainly wasn’t bothered that 12 Memories never reached the levels of success The Invisible Band had achieved. Not even when Coldplay became, well, COLDPLAY? After all, Chris Martin was never shy in proclaiming his love for, and debt to, Travis. Paying due respect, he once said that the Scottish outfit were “the band that invented my band and lots of others”.

“We were very different beasts as bands,” offers Payne. “They were a bit more strategic. And a bit cleverer!” he laughs. “Put it this way: they’re university, we’re art school. That’s the fundamental difference. We’re a bit more chaotic and, as they say round here, haun’ [hand] knitted. But you can’t begrudge them anything because they just worked their balls off, and are completely driven and single-minded. We’re a bit more vague.”

But surely their outsized – and indebted – success rankles?

“No,” shoots back Healy, “because there are two ways to write songs: you can divine them or design them. I’m a song diviner, Chris is a song designer. That’s how you can supersize songs, when you design them. And he’s brilliant at it. I’ve watched him doing it and he’s a wonder.

“I can design,” Healy clarifies. “But I’m more like your guy who sits on top of the hill, closes his eyes and waits for lightning to strike. Whereas Chris is off making a lightning machine to create the lightning. That’s the difference. And that’s the industry we’re in. It’s 99 per cent design and one percent divine. I would take divine over design any day. There’s more important things to life than being the biggest band in the world.”

Indeed. Surviving, literally and figuratively, for one thing. But after The Invisible Band, I wonder how it feels to – more meaningfully now – become more of an invisible band.

“You get used to it!” Dougie Payne laughs again. “Up till the exhaustion years, I enjoyed the success, the thrill of it all. So, yeah, there’s a part of me that goes, it’d be nice to play Wembley again. But success doesn’t always have to be [measured] that way. There’s a level of success to still doing it, and doing it as the four of us.”

Up till the exhaustion years, I enjoyed the success, the thrill of it all

Fran Healy, as is his wont, gets, firstly, analogical, and then philosophical, as he ponders what The Invisible Band did for – but also to – Travis. “Travis are built to be on the ground. Someone stuck a rocket and wings on us for a while, and we shot it into the air, and we were like, ‘woohoo, look at the view!’ Then we came back down again. We’re better and happier on the ground. That is us.

“But The Invisible Band was more than just an album. It was a reckoning, for us, as friends. As musicians. We had to realise there are limitations to where you can take something. And I’m happy to say, we passed the test. We came through the other side of it, with more sense. Our friendships were tighter. Our expectations of what we wanted to do changed. And that was that.”

‘The Invisible Band: 20th Anniversary Edition’ (Concord) is released on 3 December

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks