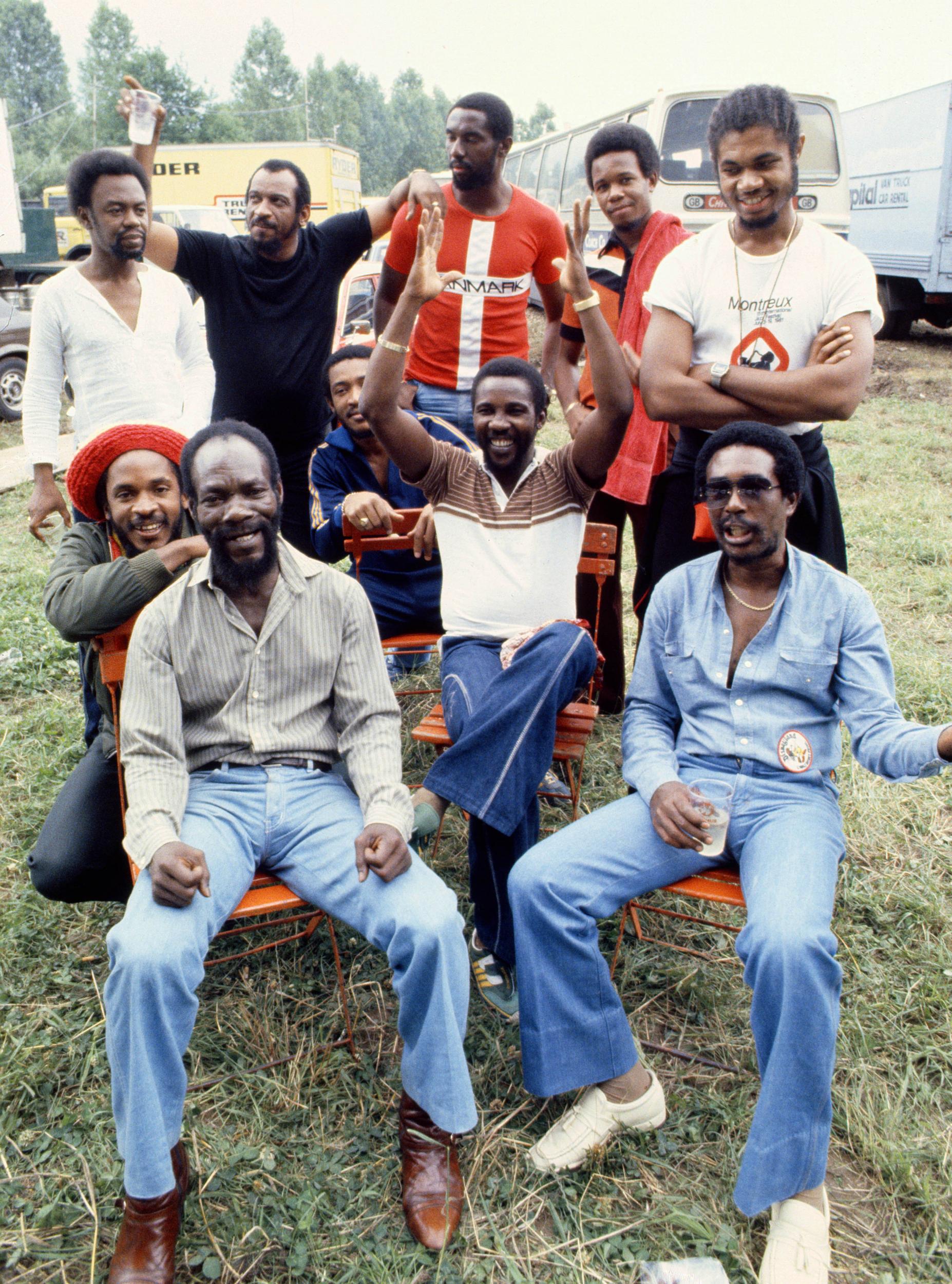

Toots Hibbert of Toots and the Maytals: ‘I think The Clash were as black as me’

The Jamaican singer who gave reggae its name talks to Kevin E G Perry about the wrongful arrest that led to a hit song, his friend Bob Marley, cannabis tea, and his first album in a decade

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In the 1960s, Frederick “Toots” Hibbert didn’t just give the emerging genre of reggae its most soulful voice – he also gave it a name. A slip of the tongue while rehearsing with his group the Maytals one day and “streggae” – Jamaican patois for someone in ragged clothes – became “reggae” in Toots’s mouth. When the Maytals released “Do the Reggay” in 1968, they intended to name a passing dance craze. Instead the newly minted word stuck to the sound they and the Wailers were helping to shape: a faster, brighter evolution of the rocksteady beat. “I never knew it was gonna be so prevalent, or so good,” says Toots, now 77, of reggae’s worldwide success. “But it feels good to know I was the one who put the ‘R’ in the music.”

Today he’s at home in the yellow-walled studio he calls the Reggae Centre, part of his pink stucco compound in the Red Hills area of Kingston. Endearingly he’s listening to his own new record, Got To Be Tough, his first in a decade. Who can blame him? The album is a joy: a riotous platter of not just reggae but also R&B, funk and soul that showcases Toots’s impressive range. He says the album comes with a timely message. “I’m giving a warning and telling you that you gotta be tough,” he explains. “Towards this corona thing that’s going around, you have to be tough. To overcome it, you have to be strong.” He’s a little hazy on the specifics, and avoids even calling his songs protest music. “I don’t call it political,” he says. “My music is just a story that tells the truth.”

Toots’s own story began on 8 December 1942, in the southern Jamaican town of May Pen – from which the Maytals took their name. His parents were both strict Seventh-day Adventist preachers and Toots grew up singing gospel in their church choir. While still a teenager he hopped on the back of a truck to seek his fortune in Kingston, staying in Trenchtown with his older brother John – the same sibling who had christened him “Little Toots” as a baby. Not-so-little Toots got a job at a barbershop and put together the Maytals as a ska harmony trio along with Jerry Matthius and Raleigh Gordon. They recorded their first album in 1962, the same year Jamaica gained its independence from the British empire. Four years later, the Maytals’ “Bam Bam” won the first Jamaican Independence Festival Popular Song Competition.

The taste of success quickly soured. Shortly after their win, the Maytals were on their way home from a concert in Ocho Rios, in northern Jamaica, when they were pulled over by the police and hauled off to the station – leaving their bags behind. Later the cops told them they’d found cannabis in Toots’s bag. He maintains he was set up. “I didn’t even smoke back then!” he says, reminding me of his strict religious upbringing. “People told untruths about me. I didn’t have no weed. People try to do things when you’re getting on top. They bring politics on you and wish you bad. They should be wishing me well, but they’re wishing me bad because of my talent. It was a setback.”

I ask him if, particularly given his experience of wrongful arrest, he relates to the Black Lives Matter movement. “I don’t relate to no movement except music movements,” he says. “Music movements is all I do.”

After Toots spent a year in prison, he turned his experience behind bars into one of his – and reggae’s – first international hits, 1969’s “54-46 Was My Number”, a song which, unlike Toot’s travel bag, really does smell like cannabis. Toots is a ganja convert these days, and isn’t surprised that parts of the world are now embracing legal weed. “The whole world is trying to catch up on what they lost, knowing that the herb is good for the nation, it comes from creation and it’s a destination,” he says, before recommending his preferred alternative ingestion method. “Everybody has got to know that you don’t have to smoke it!” he insists. “You can boil it and make a joint in a cup of tea. It’s not going to do you any bad! You go to the greenhouse or the drugstore and get just the right amount to make a cup of tea. It’s good!”

In the first ever Jamaican-produced feature film – 1972 classic The Harder They Come – Jimmy Cliff plays Ivan, a young man who, like Toots, travels to Kingston from rural Jamaica to seek his fortune as a singer. When Ivan steps inside a studio for the first time, the band he sees recording are the Maytals. His eyes light up with wonder, his lips starting to move along with Toots’s vocals.

That moment helped introduce the Maytals to a global audience, but thanks to the Windrush generation of Caribbean migrants, the Maytals already had a strong fanbase in Britain. In 1970, they’d played Wembley Stadium with Desmond Dekker and a handful of other groups, an early international show which still stands out in Toots’s memories half a century later. “The first place I was excited to play after Jamaica was London,” he says. “At Wembley Stadium, everybody rolled out for me.”

Over the next decade, reggae would seep into the music of British punk bands like The Clash and The Specials. These days an all-white band like The Clash might be accused of cultural appropriation for the way they lifted ideas from reggae artists like Toots, but he says he never saw it that way. “I was excited!” he says. “I think they were as black as me! I was happy then, and I’m still happy now that they did it.”

It was with one eye on world domination that the Maytals, by then renamed Toots and the Maytals, recorded their peerless 1972 classic Funky Kingston. The album was co-produced by Island Records boss Chris Blackwell, who then did the same for Bob Marley’s breakthrough Catch a Fire. Toots says he and Marley were never rivals. “We always enjoyed hearing each other singing – ska music, uptempo music, and reggae music,” he remembers. “My memories of that time are of happiness. The Maytals and the Wailers always had a good time together. It’s good to remember where this music comes from.”

Toots would hang out with Bob at the Marley compound on Hope Road, and remembers telling his friend they should cover one of his songs together one day. “I told him his songs are my favourites,” he remembers, “And that one day I would sing one of them with him. Since he’s gone, I decided to sing the song with his son, Ziggy.”

Their version of “Three Little Birds” is a highlight of Got To Be Tough, cranking up the tempo while holding on to the original’s magical ability to brighten even the bleakest day. Singing that particular song with Ziggy clearly meant a lot to Toots. “It felt just like I was singing it with his father,” he says.

What’s remarkable about the cover is how unsentimental it sounds. Like the rest of Got To Be Tough, it feels urgent – a statement of resilience and continued purpose from a true musical original. No wonder Toots is still blasting it through the speakers of the Reggae Centre. He tells me he’s dreaming of the day, hopefully not too long from now, when he can go out and play it live to people. He says he’s missing something very specific. “When you come to my show, if you check, it’s black people and white people, young people, and big people like myself,” he explains, before turning mystical. “Then I become them,” he says. “And they become me.”

Got To Be Tough is out now via Trojan Jamaica/BMG

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments