Sex, drugs and on the dole: The Streets’ Original Pirate Material at 20

A dispatch from the barstool resistance, Mike Skinner’s sensationally successful debut album loomed over generations of English social commentary, inspiring artists from Little Simz to The 1975, writes Jazz Monroe

Before he was a man, Mike Skinner was a ladies’ man. A thoughtful but popular kid prone to epileptic seizures, the young Skinner whistled through school with accidental bravado, impressing girls with his sensitivity and, to his constant surprise, getting punched by their exes. In his 2012 memoir, The Story of the Streets, he describes realising that when “a muscular, angry 16-year-old from Birmingham tells you, ‘It’s all right, you can have her, I don’t give a s***,’ that is actually code for ‘If you get off with her I’m going to be really upset, and I will then pick a fight with you that I won’t ever need to explain the reasons for.’”

Skinner learnt the hard way that romance and brutality came hand in hand.

In 2002, 20 years ago this week, Original Pirate Material put Skinner’s seductive powers to the test. In vignettes illustrating a “day in the life of a geezer”, the 22-year-old’s debut album used his winking naivety and cocky charm to render a banally enchanting Britain. He casually valourised a cast of daydreamers and hedonists otherwise disparaged as do-nothings and yobs, elevating (but not fetishising) the struggle. Where contemporaries the Libertines romanticised inner-city grit with fantasies of Albion, Skinner was content to peel beer labels, scrape grinders and carouse off on legendary benders. On Original Pirate Material, reality was romantic.

Before his state-of-the-nation anointed him one of the nation’s main characters, Skinner was living the low life: “Sex, drugs and on the dole,” as he quipped on “Has It Come to This?” He had grown up in a semi-detached house in suburban Birmingham, parlaying his rap and engineering obsessions into experiments with Casio keyboards, tape loops and LL Cool J-inspired verses. One day, a girl at school got wind of the secret project and mocked him into early retirement. He quietly rebranded as a beatmaker-about-town. “It wasn’t f***ing 8 Mile,” he admits in his memoir. “It was just a load of kids driving around in Ford Escorts smoking extremely strong skunk.”

By his late teens he was back on the mic, finessing pastiche raps and bombarding New York labels with demos. Their response – that the scene was congested enough without opening its borders to the Midlands – sparked an epiphany. “It was one thing to rap in my own accent, but another to make music that sounded like it came from the same place I did,” Skinner writes in the memoir. The trick was to combine the storytelling of his beloved East Coast hip-hop (primarily Wu-Tang Clan, Nas, Erick Sermon and Gang Starr) with homegrown garage beats, kitchen-sink scenes and, on debut single “Has It Come to This?”, a slice-of-life chronicle evangelising about the comforts of urban decay.

When the single went top 20, an emboldened Skinner rented a room in Brixton to finish his album, recording vocals in a sweltering wardrobe stuffed with bedsheets. He became a connoisseur of tog ratings: “The thickest possible duvet is best for the acoustics, but you need to physically survive as well,” his memoir elaborates. He was hoping the bedroom LP would impress a few junglist mates in Birmingham. Instead, within a month of its release, he was nodding vacantly at Brooklynites in ironic wifebeaters as they pronounced him a man of the people.

In a typical review, Uncut’s Simon Reynolds named Original Pirate Material his album of the year, aligning Skinner with Irvine Welsh in the way he “creates an authentic poetic spark from the base materials of UK demotic language”. In sales terms, Skinner’s boast of being “cult classic, not bestseller” loosely bore out – the album peaked at No 12 – until superhit “Dry Your Eyes” (from his next album A Grand Don’t Come For Free) propelled the debut into the top 10 two years later. Both sides of the Atlantic, the record was ubiquitous in album of the decade rundowns, topping The Observer’s list in late 2009.

Despite the abundant column inches, the Streets’ mythos remains largely inexplicable, especially to Skinner himself. “I’m not a very good rapper,” he begins his memoir. “There’s never been any doubt about my production, but when it comes to my rapping, it’s more like, ‘He just kind of has the right to do that, cos his beats are quite good.’”

This comical misjudgment of the Streets’ appeal presumably stems from Original Pirate Material’s profusion of crowbarred rhymes and verbal typos (“Shop’s got special perchant for the disorderly” – perchant?!). But Skinner’s innocence and awkwardness – the flicker of doubt in that faux-ballsy brogue – are key to his allure as a stylist. It is scary to think how much valuable information has been muscled from my memory banks to make space for ludicrous bars like “Far gone on one, call me Baron Von Marlon”.

Some of the praise pouring in made Skinner wary. British journalists tended to explain the Streets through racially loaded contrasts to gangsta rap, a genre that puritanical critics maligned but Skinner adored. One article framed the Streets as “bling-bling’s antithesis” even as he lamented destroying his Valentino and Dolce & Gabbana jeans in a tumble-dryer explosion.

He played the part regardless, navigating early press in chaotic fashion: he chain smoked, necked kebabs, chatted up passers-by, pontificated about 9/11, shouted out ragga and jungle heads, denounced Radiohead, blanked on Mark E Smith comparisons and sized up journalists with questions like: “Has anyone ever called you a muppet? When was the last time you called someone a slag?”

Original Pirate Material’s loftier moments could have undermined his people’s-poet image, but he was too endearing to fail. Set to grandiose strings, “Turn the Page” portrays a gladiator emerging from a razed garage, extravagantly depicting Skinner’s split from the UKG scene. That the man hyped as the laureate of stoned video gamers was suddenly spouting messianic prophecies, a minute into his debut album, should have boded poorly. But it made a funny kind of sense. Skinner rarely tried to be likeable, or even relatable – he wanted to be understood, egomaniacal delusions and all.

“Weak Become Heroes” introduced us to his sentimental side, as well as his genius invention European Bob, described by Zadie Smith as an “archetypal figure for our generation” – a derelict raver-cum-sage akin to Peep Show’s Super Hans. Alloying halcyon house with rave melancholy, the song has endured as an official epitaph to the party era cut short by the Criminal Justice Bill.

The album’s sensational success was conspicuous at a time when British rap struggled for critical and popular credibility. Although Dizzee Rascal and Skepta eventually reached similar heights, Skinner – like Plan B and Lady Sovereign – had never had to prove his chops on the pirate circuit, as the journalist Chantelle Fiddy observes in Inner City Pressure: The Story of Grime.

“Skinner’s subject matter appealed to a white mass market,” Fiddy told the author Dan Hancox in 2006, noting grime’s limited crossover at the time. “But the US majors have no problems selling black rap stars’ subject matter to a white mass market, either in the US or over here. So something must be lacking in the UK majors’ marketing departments.”

Skinner’s subject matter appealed to a white mass market

To put it another way, Streets forebears So Solid Crew may have straddled daytime and evening radio – even beating the Streets to the Top of the Pops/Jools Holland double – but Skinner alone would receive a subsequent invite to Radio 4’s Front Row. Nobody knew quite what to do with him, but since he fit the profile of relatability, the novelty worked in his favour.

For all its charms, Original Pirate Material was never quite the post-garage watershed that “Turn the Page” had dramatised. That honour went to another bewilderingly young talent, Dizzee Rascal, whose 2003 debut, Boy in Da Corner, became the first true grime opus. But on Original Pirate Material’s 15th anniversary, grime pioneer Jammer told the Fader: “A lot of sounds and ways of putting records together were taken from that Mike Skinner album. He was telling us a story we wanted to know more about. It’s one of the UK blueprint albums.”

For his part, Skinner stayed humble. “I wasn’t a talented enough rapper [to] have an influence on rap,” Skinner writes in his memoir. “I had an influence on the Arctic Monkeys.” Indeed, a young Alex Turner said he walks “the tightrope between Mike Skinner and Jarvis Cocker”, and in this direction Skinner’s fingerprints have spread.

If nothing else, The Streets’ sensibility has loomed over the subconscious of English social commentary. Sleaford Mods’ low-stakes polemic and rudimentary beats suggest a parallel universe in which Skinner was into Mark E Smith after all. Kae Tempest appraises human folly and kindness with wide-eyed, Skinner-esque candour, over music similarly indebted to the sounds of diasporic London. And the gulf between Little Simz and the 1975’s Matt Healy – two leading British lyricists with seemingly little common ground – narrows when you learn they are Streets fans. Both deliver introspective social commentary with an intense sincerity that can be thrilling, or even unnerving, as is Skinner’s trademark.

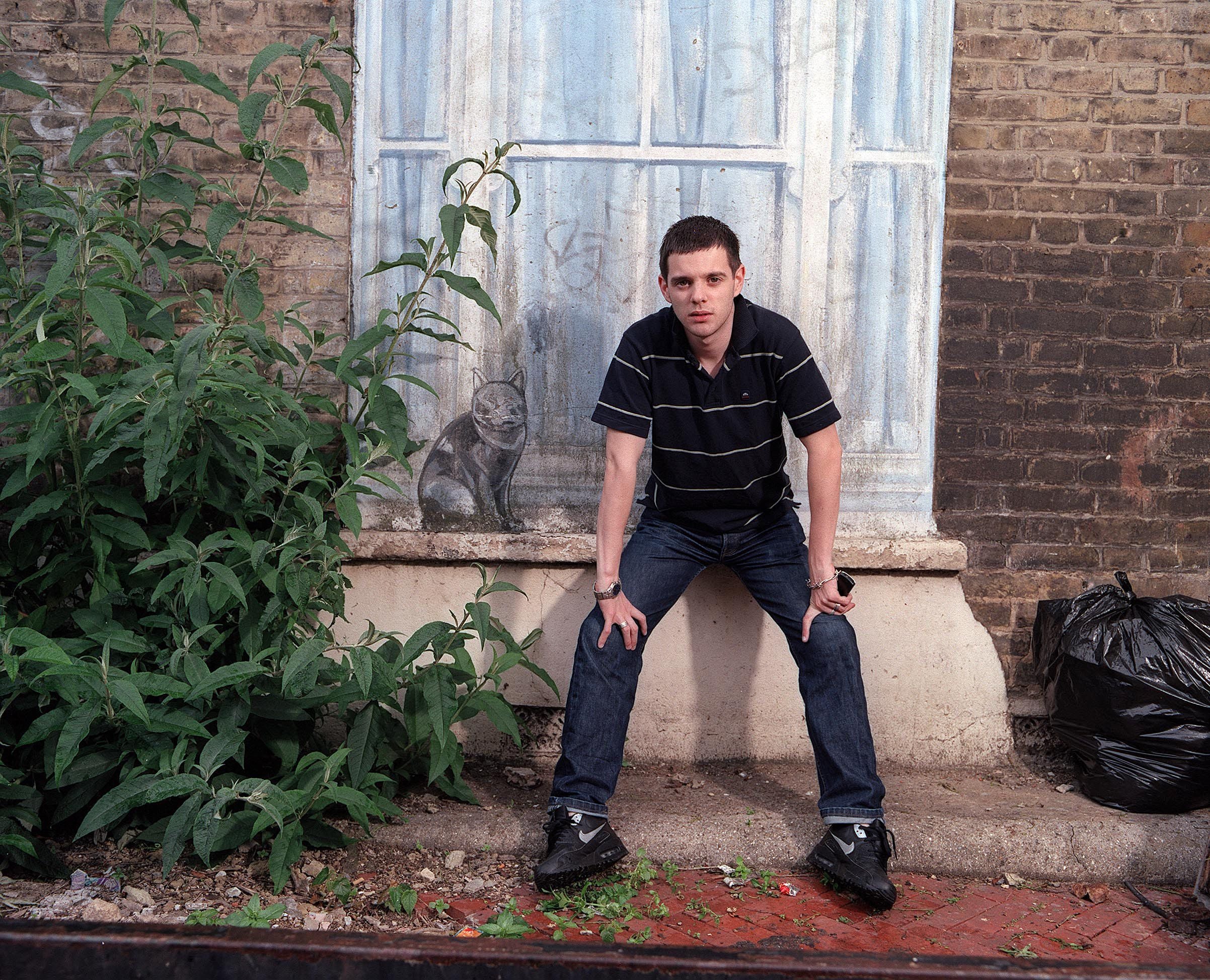

![‘I wasn’t a talented enough rapper [to] have an influence on rap.’ Skinner wrote in his memoir](https://static.the-independent.com/2022/03/21/09/shutterstock_editorial_385421h.jpg)

Skinner himself feared that Original Pirate Material was a fluke. He embarked on a journey from “screenwriting gurus to cognitive behavioural therapy to art history” in search of lyrical anchorage. It led him to a set of country songwriting manuals, whose wisdom informed many songs that endure and also plenty, amid the cod-spiritual koans and war-of-the-sexes platitudes of his later records, that does not.

By that time, 2004 follow-up A Grand Don’t Come for Free had already secured his legacy, but Original Pirate Material defined a moment of its own. In 2002, the album sliced through a culture steeped in aspirational politics, as movements ranging from rock’n’roll-star Britpop to survivalist gangsta rap were cornered into echoing the neoliberal credo: that the underclass is here to stay, but you can get out if you grind hard enough.

Nobody suggested we band together and rise up – this wasn’t the 1970s – but here at the back of the class, shrugging and hungover, scribbling flirty notes on paper aeroplanes, was a man determined to reject the aspirational treadmill. Original Pirate Material was Skinner’s dispatch from the barstool resistance, surveying all that awaits those left behind. Album closer “Stay Positive” preaches individualism (“I ain’t helping you climb the ladder, I’m busy climbing mine...”), but by that time, his words had instilled just the opposite message: that no disenchanted deadbeat, however addled or angry or brutalised, was beyond redemption. What could be more romantic than that?

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks