The rocksteady rise of Rastaman vibrations

An upcoming BBC documentary tells the story of reggae in Britain, from its ska roots to UB40. Elisa Bray goes uptown top ranking

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It is a genre that has inspired decades of music, and yet British reggae is too often overlooked. A new documentary from BBC4, Reggae Britannia, seeks to put that right, as it takes us through the influence of Jamaican music on British culture from the early 1960s to the late 1980s.

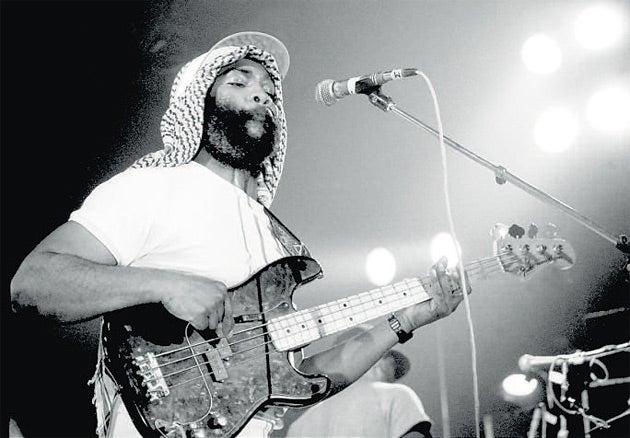

Following on from its Soul Britannia and Folk Britannia counterparts, Reggae Britannia features Paul Weller, Paul Simonon of The Clash, Jerry Dammers of the Specials and Boy George celebrating the influence of the genre on their own music. It is preceded by a concert at the Barbican in London tomorrow night showcasing members the UK reggae scene, many of whom also appear in the documentary, including Ali Campbell, Neville Staple of The Specials, Dennis Bovell, Janet Kay, Carroll Thompson and Dennis Alcapone.

From its beginnings in Jamaica, ska (which, we learn, is an onomatopoeic word for a guitar on the off-beat) and rocksteady found their home on releases by Chris Blackwell's early Island Records and Trojan Records. Despite Top 10 chart hits which proved the UK's taste for Caribbean rhythms (Millie Small's "My Boy Lollipop" in 1964, and later Desmond Dekker's "Israelites", the first UK reggae No 1, and "It Mek"), reggae was considered novelty music by the media.

It was shunned by British radio – Radio 1's No 1 DJ Tony Blackburn dismissed it as "rubbish". Record labels even started doing remixes, reducing the bass and adding an orchestral feel to sweeten the music, making it more palatable to the British ear, in a bid to get it onto the UK airwaves.

Reggae Britannia also shows us the plight of West Indian children who found themselves out of place in 1960s Britain, unrepresented in their schooling. They found their identity through any records they could lay their hands on, particularly imports and those released by Trojan Records and Island.

David Hinds, who fronted one of the most successful Brit reggae bands, Steel Pulse, recalls his feeling of alienation, on being taught "things that had nothing to do with our development, our growth spiritually, physically, mentally". As Brinsley Forde, founding member of British reggae band Aswad, says, they took their music to school. "It was our music, it was something that we said was ours".

Still, an underground scene was bubbling, and the music could be found via sound systems in dancehalls, and at legendary "house parties", across the country. At these, communities would congregate to be inspired by the local reggae bands performing in the basement.

Jamaican DJ and producer Dennis Alcapone, who moved to Britain in the mid-1970s, recalls: "Jamaicans in the early days weren't accepted in certain places so they made their own entertainment venues in their houses. People would come in and hear the music and be influenced by it. It was like a reunion of the community; people from all nations used to attend. Because of the racial tension at the time, it made the community closer."

The parties spread to Birmingham, too, where there was a large West Indian community. UB40's Ali Campbell reminisces about his earliest experiences in reggae that would provide the foundations for his chart-topping band. "When I was 11 or 12 I'd sneak out the house and go to blues parties. They'd take over derelict houses for the night and fill them with speakers. The sound systems would be so loud that when they brought the bass in the place would shake and windows would crack – it was an assault on the senses. A lot of people would run out and throw up. It was the only way to listen to reggae and dub."

The sound system was how the latest singles were heard in Jamaica, and became essential to the development of reggae in the UK in the absence of radio play –"our BBC and ITV" as one member of Big Youth said.

For the musicians performing at the Reggae Britannia concert, the all-star cast will provide a welcome rekindling of memories of when the West Indian culture started feeding into the UK. "They are people from my era", says Alcapone. "It certainly will bring back memories. All the original people that were setting a trend at the time, those were the people who laid the foundations and the rhythm for us. It was a wonderful time."

With the arrival of Bob Marley, reggae music moved beyond being considered a novelty. When Eric Clapton covered some of his songs, it was Marley's biggest break. But while reggae was now regarded as a credible genre by the masses, British reggae artists were finding it hard to break through. People were suspicious of their reggae's authenticity.

Matumbi, whose guitarist Dennis Bovell became a leading dub producer in London, and later worked with The Slits, were one of the first British acts to make their name, and with the advent of punk rock, things looked up for British reggae. Punk-rockers identified with the alienation felt by young black British, and soon rock and reggae fans alike were mingling at Marley's gigs. British reggae groups such as Birmingham's Steel Pulse and Aswad began to break through, and when punk-rockers started showing reggae influence – the Clash with their cover of "Police and Thieves" for example – the crossover paved the way for a number of new British strands of reggae.

One of those was the 1979-1981 2 Tone ska movement of Coventry's Specials, with the Beat, Madness and The Selecter also fusing reggae and punk. Pauline Black, singer of The Selecter tells me: "Reggae fell out of fashion fairly soon after Bob Marley died. Like all of these things, if you get a white artist that takes up the cause like The Specials, it gets presented in a way that everyone in the country feels they can identify with. The fact that Johnny Rotten started going to reggae shows made it easier for the 2 Tone movement to form multicultural bands before anyone had heard the word multicultural. The Clash were dabbling in it as well and that paved the way for 2 Tone music. People were used to punk and reggae music, but we put the two together, creating punky reggae with an up-beat."

Black, who grew up as a mixed-race girl with white adoptive parents, credits British reggae music coming to the fore with helping her to find her identity – as it did for others. "Without that I feel that 2 Tone wouldn't have happened", she says.

UB40 popularised reggae with their chart hits "Red Red Wine" and "Can't Help Falling In Love", and their 1983 covers albums of reggae songs, Labour of Love. They had the tag of "white reggae band" thanks to white frontmen, brothers Ali and Robin Campbell, but in fact half the band were black. Growing up in an immigrant area in the 1960s and 1970s, Campbell couldn't fail to be influenced by his peers.

"I grew up on reggae, like my black friends. The music that elated me and still elates me is reggae. When I was 17 I would help out with my father's folk club. When he went on tour me and my brother turned it into a reggae club and put on Matumbi and Steel Purse. That's why when I was with UB40 we did the Labour of Love records. They're songs that made me love reggae. I started UB40 to promote reggae and dub music and I do the same now with my new band, The Dep Band.

"It's ridiculous that reggae gets so little play on the radio. I've always been angry about it. It's the most influential music genre of the past 35 years. Without a doubt."

Reggae Britannia, tomorrow, Barbican, London EC1 (www.barbican.org.uk; 020 7638 8891). 'Reggae Britannia' is brodcast on 11 February at 9pm on BBC4, followed by a film of the Barbican concert at 1.20am

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments