Firestarters not welcome: How The Prodigy’s The Fat of the Land fell out of favour

Raved about then, ignored now – whatever happened to the band’s incendiary 1997 album? Ed Power revisits its multiple controversies to find out

The crab snapping its claws on the cover of The Prodigy’s The Fat of the Land can justifiably claim to be the most famous crustacean in pop. It also has become a slightly unfortunate metaphor for a record that raised a huge, click-clacking ruckus when it first came out, but which has ultimately ended up a sideways shuffling oddity, buried slightly in the sands of history.

On its release in 1997, The Fat of the Land was heralded an instant masterpiece. “The album rools,” said the NME of this molten mash-up of rave and punk. “A thrilling, intoxicating nightmare of a record, an energy flash of supernova proportions,” said Rolling Stone, adding “There’s no telling how far The Prodigy’s marriage of man and machine could take them.” “Mozart at the wheel of a monster struck,” enthused The Guardian.

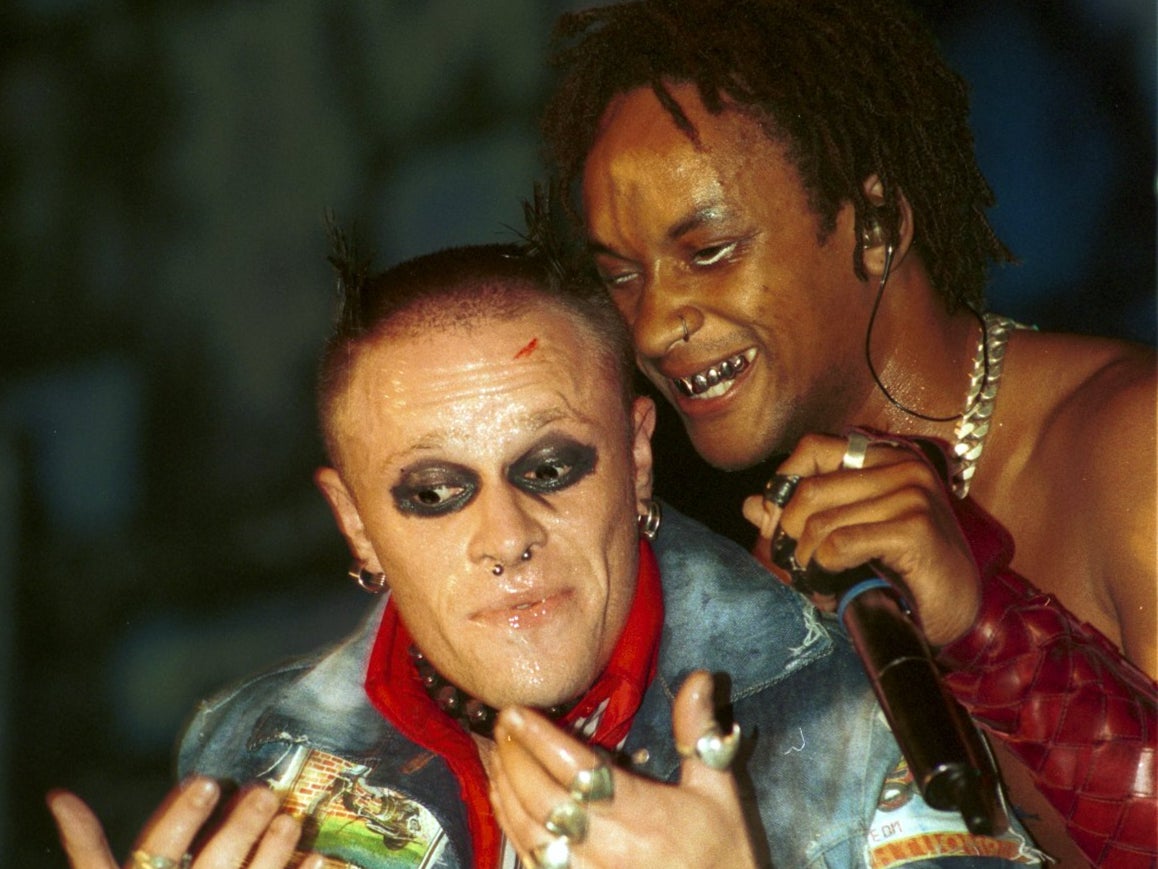

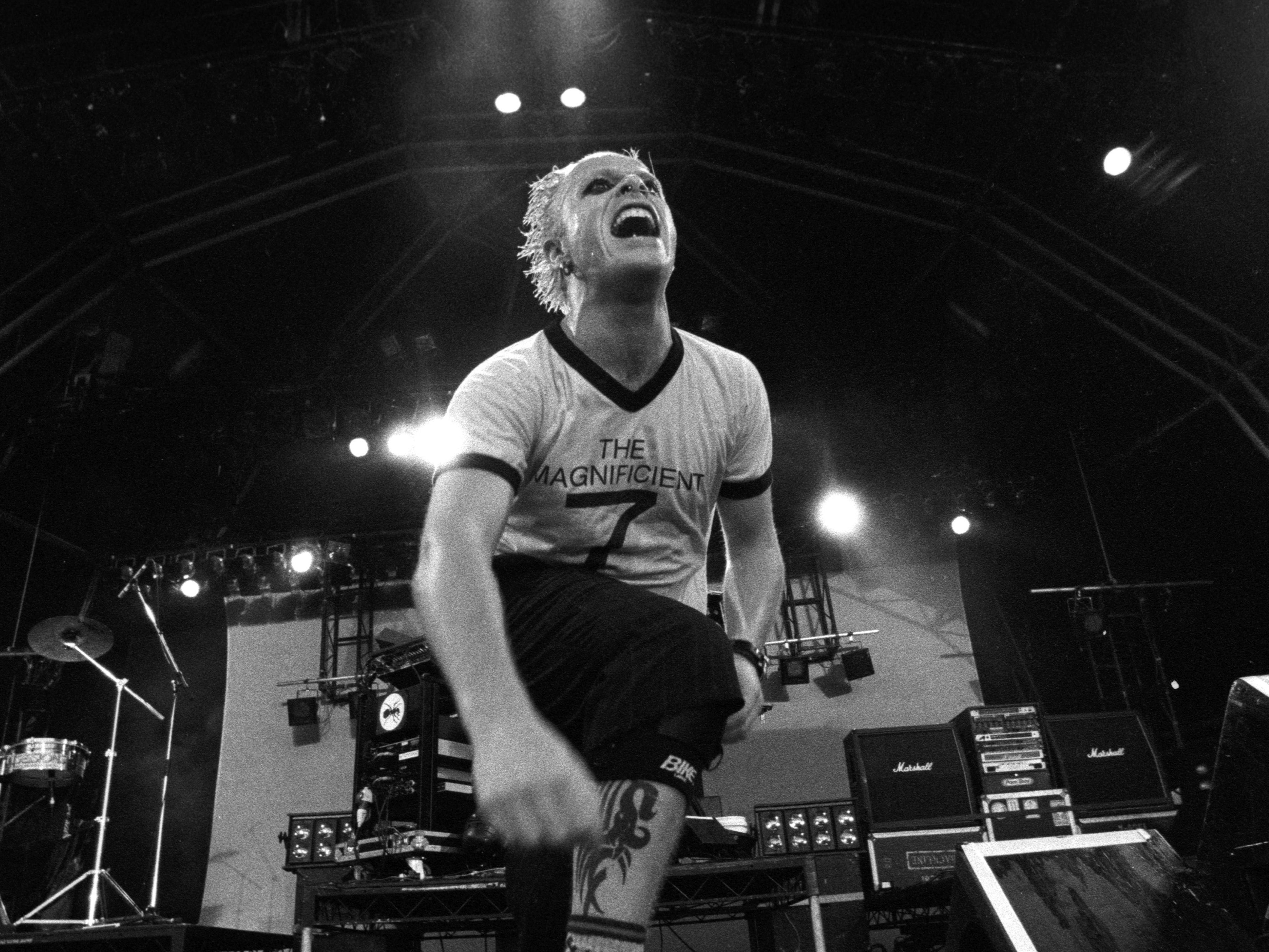

Yet in the decades since, The Fat of the Land has been stripped of its landmark, era-defining status. It turns 25 on 1 July – but does anyone really, truly care? Nobody would claim this is a forgotten masterpiece or is hurtling towards obscurity. Eyes popping, mohawk bristling, the Prodigy’s late frontman, Keith Flint, is a Nineties icon – as instantly recognisable as a Spice Girl or a Britpop star in a zip-up trackie shouting “Oi!” at the traffic.

The Fat of the Land’s legacy, though, feels ambiguous. And not just because the first song, “Smack My Bitch Up”, opens with the lyrics “change my pitch up/ smack my bitch up”. Or because it is packaged with a Hermann Goering quote (see below).

The fact is that The Fat of the Land – if universally acclaimed when it came out – feels as if it has been left behind in the decade from whence it came. When Rolling Stone listed its “100 Greatest Albums of the ’90s” in 2019, there was no room for the Prodigy. Pitchfork similarly omitted The Fat of the Land from its Nineties “Best of”. Even the almighty Google algorithm suffers Prodigy amnesia: enter “best album of the 1990s” as a search term and The Prodigy are notably absent.

But in 1997 that was not the afterlife anyone imagined for The Fat of the Land. It was seen as an irresistible juggernaut – a record that took rock and dance and, out of that squalling synergy, forged something new. “The problem that The Prodigy were trying to resolve, if you like, is how to maintain the intensity of the raves they’d come of age with in the late 1980s and early 1990s, especially in the context of their playing large festivals and stadiums and being listened to in front rooms and halls of residence,” says Dr Paul Rekret, a researcher and teacher in political and cultural theory at Richmond, The American International University in London.

“Their solution was to try to amplify the rockist elements of the music: more sirens, faster breaks, more screaming, more outrageous outfits and lyrics, abandoning rave PA anonymity for rockist line-ups on stage, and so on. This built on their attempt to do the same thing with [early single] ‘Charly’, to build the intensity of a rave but through a sneering angst and fast and hard breakbeats.”

It worked, for a while. There seemed no stopping The Fat of the Land. Building on the momentum of 1994’s Music for the Jilted Generation and landmark singles such as “Poison” and “Voodoo People”, their third album positioned The Prodigy producer Liam Howlett and his Essex bandmates as one of the most essential forces of their era.

It wasn’t merely that The Fat of the Land was loud and aggressive. Amid the slamming grooves, it was a record of hidden depths. Absurd though it sounds, you could even call it subtle in places. “Breathe” skilfully spliced the pummelling force of industrial rock and the rapture of the dancefloor; “Mindfields” was the missing link between rave and the emerging big beat scene. And, with Kula Shaker’s Crispian Mills on vocals, “Narayan” married pre-millennium angst with limb-flailing 2am euphoria (“And you feel it burn!/ Your time has come,” sang Mills as the 20th century seemed to turn to ashes around him).

The Prodigy certainly felt, in the moment, as important as Radiohead, whose OK Computer had come out several weeks prior to The Fat of the Land. As pointed out, the critics were reaching for their shiniest superlatives. Commercially, too, The Prodigy were all-conquering. At one point that summer they were outselling Radiohead by a factor of eight to one.

Everybody loved them. Bono asked Liam Howlett to remix a single off U2’s Pop (U2’s misfiring tilt at trip-hop – a sort of Fat of the Bland). Madonna – who’d signed the Prodigy to her US label, Maverick – wanted them to produce her next album. David Bowie begged Liam Howlett to collaborate. He turned them all down.

The Fat of the Land was unleashed as the Prodigy were still riding high on the notoriety of 1996’s “Firestarter”. The album’s lead single had provoked an outcry when the video aired on Top of the Pops. Wide-eyed, his hair with a life of its own, Flint looked like the devil himself. Shot in skittering black and white, he had emerged from the depths of a corrugated tunnel to deliver such devastatingly dark lines as “I’m the self-inflicted, mind detonator” – lyrics that drew on the self-esteem issues he had suffered through his life.

With parents complaining that the video had scared their children, the “Firestarter” promo was prohibited by the BBC. An old school moral panic was soon underway: “Ban This Sick Fire Record” demanded the Mail on Sunday.

Today, it feels ludicrous anyone could have been frightened of Keith Flint – he looks more like a Doctor Who baddie than a nightmare visitation. But to put out a single titled “Smack My Bitch Up” was justly regarded as in poor taste. The Prodigy claimed the song was a tribute to early hip hop “B-boy” culture, the offensive line coming from “Give the Drummer Some” by Howlett’s favourite rap group, Ultramagnetic MCs.

“At the end of the day,” Keith Flint told Rolling Stone, “the girls who come to our shows are hardcore girls, and they don’t look at it as that. If some girl in an A-line flowery dress decides there’s some band somewhere singing about smashing bitches up, let’s get a bit militant. They don’t know us. They never know us. They never will.”

“It’s so offensive,” Howlett said in the same interview “that it can’t actually mean that. That’s where the irony is.”

Howlett never expressed any regrets. However, Richard Russell, of their record label XL, had second thoughts about “Smack My Bitch Up”. He addressed the controversy in his 2020 memoir, Liberation Through Hearing.

“Is it art? Yes, just about, and a great deal of art is not pleasant,” he wrote. “Was any woman ever abused because of The Prodigy? My instinct is no. But how can I be sure? So, do I regret releasing a single on XL with the title ‘Smack My Bitch Up’? No. But I doubt that I would do it again.”

Incredibly, The Fat of the Land also came packaged with a quote (slightly altered) by Hitler henchman Hermann Goering. “We have no butter, but I ask you, ‘Would you rather have butter or guns? Shall we import lard or steel?’ Let me tell you, preparedness makes us powerful. Butter merely makes us fat.”

They weren’t the first outlaw rockers to flirt with Nazi invective and imagery. Bowie declared in 1976 Hitler was “one of the first rock stars”. Joy Division’s Ian Curtis shouted, “Have you all forgotten Rudolf Hess?” from the stage (and “Joy Division” was itself a reference to sex slavery in concentration camps).

This was a taboo as old as rock itself. All the way back in 1966 The Rolling Stones’s Brian Jones went on stage in Munich in a Nazi uniform. And fascist regalia was bang on-trend in the early years of punk, with Siouxsie Sioux and Sid Vicious among those flirting with Third Reich iconography. Nonetheless the feeling in 1997 was that The Prodigy should have known better.

“It just fitted in well with the whole vibe of the album,” Howlett told Rolling Stone. “Not obviously from the Nazi point of view, but B-boy culture. It scared me when I read it. It’s such a powerful quote, but it’s really scary: butter or guns. It stuck in my head. I thought it was perfect for what we wanted.”

The Fat of the Land remains beloved by fans – a not-inconsiderable demographic. “The breathtakingly huge global fandom love the album, but I think contemporary media would have a hard time defending ‘Smack My Bitch Up’ now so it’s better not to celebrate problematic albums,” says Martin James, professor of creative and cultural industries at Solent University, Southampton and the author of several books about The Prodigy.

“Hip-hop fans of the time recognised the phrase to mean ‘handle my business’, so it spoke of hip hop’s misogyny and Liam Howlett’s fandom of hip-hop culture. Lots to unpick in that track and how passive misogyny was central to the 1990s Loaded era.”

Legacy was never something the Prodigy were too bothered about. With their early hit “Charly”, they had become the faces of rave culture – but they quickly abandoned the scene, feeling it had lost its outlaw spirit. And even as The Fat of the Land broke sales records, they stayed gloweringly beyond the mainstream.

“The Prodigy were always outsiders. They walked away from hardcore rave before anyone else,” says James. “They played rock venues like the Marquee before it was OK for dance bands to do that. They played festivals when most ravers were still doing live PAs. They refused to do TV – apart from one early performance on Normski’s show [Dance Energy on BBC Two]. They refused to do anything that was just for the exposure. They remained on an independent label when majors were queuing up.”

Ultimately, perhaps the lesson is that The Prodigy were determined to be The Prodigy, for better or worse. That was their greatest strength – giving them the confidence to move beyond rave and to fearlessly combine the seemingly disparate genres of punk and electronica. And perhaps it was also a weakness.

“It took Liam years to come with the follow-up, Always Outnumbered, Never Outgunned [from 2004] but the public didn’t take to it and the media pretty much ignored it,” says Martin James. “I was talking to the head of Radio 1 at that time and he said they weren’t playing The Prodigy because they were too aggressive, too scary for the time. It was 2004: no room for The Prodigy among all of that new millennium positivity.”

If the mainstream didn’t want The Prodigy, it appeared that the feeling was reciprocated. And when the spotlight moved on, they were in no hurry to reclaim it (and had, if anything, added to their infamy with the 2002 single “Baby’s Got a Temper” and a chorus that “playfully” references date-rape drug Rohypnol). And so, when it comes to why The Fat of the Land isn’t celebrated as a classic, maybe the answer is that The Prodigy simply never wanted to be part of anyone’s pantheon other than their own.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks